Mark Levinson No33H Monoblock Amplifiers (Super Exclusive)

Original price was: R299,000.00.R150,000.00Current price is: R150,000.00.

Chances are you’ve never seen an amplifier quite like the Mark Levinson No.33H. That’s because there’s only one other amp that’s anything like it: the Mark Levinson No.33, upon which it’s based. Both amps are more tall than broad, looking almost as though they’re resting on their ends; heatsinks cluster around their side-panels. In the city of the High End, the No.33 and No.33H are skyscrapers standing tall above the warehouses.

When Madrigal first unveiled the No.33, they were drawing a line in the sand. “This is everything we know about building amplifiers,” they said. But they weren’t prepared for the public’s response to their No.33 Reference statement—at $33,000/pair, they figured they’d sell a few a month, but that there could never be that much demand for a heavy (well over 200 lbs), massive, 300Wpc monoblock. They were wrong. “The response was overwhelming,” said Jon Herron, head of product development at Madrigal.

C’mon, Jon—”overwhelming”?

“We often had to carry No.33 back-orders from one month to the next. The labor involved in building each amplifier is prodigious, and the space necessary for all of the major subassemblies during the final assembly and testing is enormous. We are therefore limited to building a maximum of between 10 and 15 pairs of these amplifiers per month. We do have other products to build.”

Realizing that many audiophiles didn’t need all the power offered by the No.33, Madrigal set out to design a half-powered version, the No.33H, which puts out 150W into 8 ohms (the power successively doubling into 4 ohms, 2 ohms, and 1 ohm). But, Madrigal is quick to point out, although the No.33H is based on the No.33, it is not a Reference product. Just as on Highlander—there can only be one.

High power

Make no mistake, the No.33H doesn’t look—or act—like a scaled-down anything. It’s huge (11″ W by 18.5″ H by 22.88″ D) and heavy (175 lbs each). And when Madrigal lists its output power, they add an ominous-sounding “assuming the wall outlet is up to the task of supplying all that power.” Wow.

Let me put the ’33H’s stupefying power capabilities in perspective: Each monoblock employs four 60,000µF capacitors, for a total of over ¼ Farad of capacitance. (By contrast, the 200Wpc No.332 uses a pair of 50,000µF capacitors per channel.)

In fact, the power supply of the ’33H is a good place to start examining the amp. It uses two independent, bipolar power supplies in order to maintain the fully balanced nature of the amp from input to output. These come off a single, Madrigal-designed 3.417kVA transformer, utilizing multiple taps to maintain the symmetry of the two bipolar supplies. (Madrigal points out that the transformer VA output of the ’33H is 70% of that for the No.33 because the voltage swing at half-power is actually 70% of that found in the ’33.)

While the No.33 uses two 2.5kVA transformers, that’s a matter of practicality, not necessity. Since the ’33H is a monophonic amplifier, symmetry for the inverting and noninverting sides of the same signal is assured.

The ’33H also employs an AC regeneration system for the input and driver stages. This drains off a portion of the ± DC power from the main supply, powering an oscillator circuit that generates pure-sinewave AC. This uncontaminated AC is rectified, filtered, and regulated. You could say the heart of the amplifier is a mini power station designed to deliver AC of uncompromised purity.

Incoming signal from the preamplifier is received using proprietary topology—again developed for the No.33—that eliminates the standard feedback point on the inverting leg of the first-stage differential amplifier. This means the two sides are truly balanced from the start. Each leg of the signal is handled differentially. The two balanced voltage-gain stages, running side by side, are essentially “double”-balanced. Even single-ended inputs are converted to balanced in the first voltage gain stage, and are run “double”-balanced in the second.

In the third voltage-gain stage, the signals are converted to a pair of SE signals of equal amplitude and opposite polarity (balanced, as we know it). Each of these signals then moves on to its current gain stage.

Forty output devices (two sets of 10 complementary pairs) are used in the output stage. This means the output terminals do not reference ground at all.

Like its big brother and the rest of the 300 series amplifiers, the No.33H is equipped with Madrigal’s Adaptive Biasing system. This maintains a state of equilibrium by referencing both the instantaneous voltage and the current required by the load to constantly determine the optimal bias. Madrigal insists that this maintains a state of equilibrium in which the bias is maintained “continuously and naturally,” but that it does not “react”—any more than a resistor “reacts” to a higher voltage by “deciding” to conduct more current. “The one fact inevitably leads to the other,” they claim.

High praise

There are those who claim there can be no audible differences between any two competently designed power amplifiers not driven to clipping. For them, the very idea of a $20,000 pair of monoblocks must seem absolutely ridiculous. All I can say is that they should steer clear of the Mark Levinson No.33H, or else risk having their tidy little hypotheses shattered into tiny little pieces.

Because the amazing thing about the ‘H isn’t that it sounds better than any other amplifier I’ve ever heard, but that it doesn’t sound like any amplifier at all. It sounds like no amplifier. It sounds as much like music itself as anything can that must rely on recordings. So you’ll have to forgive me if I come up a bit short in describing what it “sounds” like. (If you think that’s too much like some kind of Zen parable, I have to agree—reluctantly, since most of the ones I know end up with the Master giving the disciple a whopping great whack.)

But I’m sure you see my predicament here. If I go on at length about how great the ’33H “sounds,” I’m forced to admit that it has a sound—which negates my argument that it is the most realistic amplification device I’ve ever heard. But if I claim that all of this is so subtle as to defy description, and mutter “You just have to hear it for yourself,” I’ll be rightly reviled as being just too wussy for words. Sigh.

For me, one of the elements that distinguishes live from recorded music is that live music is not constrained. Take Phil Myers, the first-chair horn for the New York Philharmonic Orchestra: Phil is loud. I want to claim that he’s so loud that we heard him in New York back when he was playing in Pittsburgh, but that would be a lie. We did, however, hear about him from all the New York players who were gigging in Pittsburgh—”Man, they’ve got a horn player who blows so hard that if he didn’t have his hand shoved up the bell, it would straighten out like a party streamer,” one trombonist told me. Of course, Phil is a consummate musician on many levels—he didn’t get to be first chair in the NYPO simply by drowning out the competition—but any description of Phil’s technique is incomplete if it doesn’t mention how hard he plays.

For many years I reveled in Phil’s power and clarity—I’d frequently choose to go to concerts simply because the program offered some choice first-chair horn licks. I always knew Phil would deliver. No matter how loud the NYPO, Phil could cut through it like a sword through silk. But recordings seldom possess this kind of limitless dynamic potential. Sometimes you can even identify the precise point at which everything refuses to get louder—to get liver. [live-er?] I never ran into this with the No.33Hs.

Actually, that’s not entirely true. Sometimes the microphones used to record the event are the limiting factor, and sometimes, of course, the mastering may be the cause—but in all my listening to the ’33Hs, the problem was never the amplifier.

Another distinction between live music and reproduced music lies in how different pitches seem to possess different velocities. You must have heard recordings where the string and woodwind overtones seem to float effortlessly, whereas the lower brass and basses seem to plonk down onto the soundstage and lie there. I sure have. In reality, we all know that tones lack any kind of specific gravity. The sounds emanating from a string bass weigh no more than those escaping from a piccolo, and they float just as gracefully upon the air. But that’s not how many systems, and many amplifiers, reproduce them. Through the ’33Hs, all music remained as graceful and as free as its most ephemeral components.

This doesn’t mean, I hasten to point out, that bass tones lacked power, heft, or impact. That was all there in spades. In fact, you may have never heard how deep and muscular your speakers can sound until they’ve been taken control of by the No.33H. And swing? Lordy, if you want to become a dancin’ fool, just slap something rhythmic onto your front end—just don’t blame me if you boogie ’til you puke.

If you wish to check off your favorite attributes, I can oblige. Soundstaging through the ’33Hs was phenomenal—deep, detailed, holographic. Tonal balance was natural, and possessed purity and clarity galore. Low-level detail never leapt out at me, but existed naturally within the musical gestalt—but it was never obscured either. There’s more, of course, but paradoxically the No.33H exists on a plane where the news isn’t about more, it’s about less.

It had no grain, no grit, no electronic character that I could detect. It had no “warmth.” Neither did it add any chilly sense of “accuracy.” It had no MOSFET blur, no transistor etch, no tubey euphony. No heightened sense of illumination into the event. It was practically nonexistent—except that it did what it did better than anything else I’ve ever heard.

High Society

This, of course, forces the question: How do the Mark Levinson No.33H monoblocks compare to the Krell Full Power Balanced 600, Stereophile‘s joint Amplification Product of the Year for 1997? After all, Martin Colloms went so far in his review last April as to claim that the Krell so rewrote the book on amplification as to require a total reexamination of Class A power amplifiers in Stereophile‘s “Recommended Components.” I’m not sure I’d go that far, but Martin is essentially correct: Compared to the Krell, almost everything else sounds broken.

Directly comparing the FPB 600 and the No.33Hs proved a logistic nightmare. Both amps required extended warmup—ie, music playing through them for several days—before either reached its optimum. The upward climb was far shorter, of course, from powered standby. The problem stemmed from my house’s wiring, which simply wasn’t up to both amps sucking all that current through the same circuit. (That’s it—my New Year’s resolution for 1998 is to rewire the house with beefy audio-only circuits.) So my comparisons are not direct A/Bs of specific passages, but are the results of longer listening sessions separated by the requisite warmup periods. Flawed? Yes, but the best I could do under the circumstances.

The differences between the amplifiers were subtle, very subtle. Both were essentially not there in terms of having an effect upon the music. And, while each was capable of kicking some major audio booty, the most impressive thing was that neither sounded like a big amp during the quiet passages. Both were delicate and graceful.

However, the Levinsons seemed to present low-level detail with less “light-against-black” spotlighting than did the Krell. Audiophiles frequently speak of silence as the “blackness” against which sounds are highlighted, but I think that most sounds appearing from silence are far less dramatic than that. In a sense, then, I’m calling the Levinson more natural-sounding for its lack of “added” drama—and I have to put “added” in quotes because that might be merely my preference. Another listener could as easily call the No.33H “duller,” and laud the Krell for its ability to extract excitement.

Allied with that ability to portray low-level detail was a sense of natural ease; I found the Levinson ever-so-slightly more transparent in the midbass and low bass. This is the quality I alluded to earlier when I praised its ability to “float” low tones in the same manner as the highs. While the Krell has superb transparency down to its low midbass, it tends to favor muscle over subtlety in the deepest regions. Yet that seems too harsh a criticism of the FPB 600: it takes charge of the bottom end in a way few other amps ever have, while remaining very attuned to the musical moment.

As did the No.33H. I compared the two amplifiers using the first movement of the Masur/NYP Mahler 9 (Teldec 90882-2), recorded live in Avery Fisher Hall in April 1994 and chosen because of my familiarity with both hall and musicians. The Andante comodo begins extremely quietly, with a three-note syncopated rhythm in the cellos and horn (Myers again, sounding forth brassily). This must have had a deep meaning for Mahler—at the movement’s climax he brings it back marked fff, hûchste Kraft (“with the utmost force”). Mahler’s friend, Alban Berg, called the riff “Death itself.” God knows, it’s forceful enough to qualify for such a frightening description.

Both amps handled the climax with ease. Both did superb jobs of conveying the emotion implicit in the intense wash of sound. But I felt the Levinson’s clarity in the bass allowed me to hear the NYP double basses as distinct entities separate from, but still members of, the ensemble. The Krells certainly conveyed their power as members of the whole orchestra, but through the Levinsons I felt as though I could actually make out Eugene Levinson, Jon Deak, et al as individual players surrounded by air and anchored to the floor of the hall I know so well, playing in unison among another 100-odd players—all blowing, bowing, and banging furiously.

Comparing the two best amplifiers I’ve ever heard to one another, I reckon one has to be better. But if I seem uncomfortable in proclaiming the Levinson to be better than the Krell, I am—until I heard the No.33H, I never would have guessed the FPB 600 had an equal. These two amps are so close in character that another listener could very easily call it the other way. I can’t imagine anyone being less than satisfied with either. Yet to my ears, no matter how slightly, the No.33H sounded like the better amp.

High hopes

“Let music be without dissimulation” could be the prime directive of musical reproduction. If so, the Mark Levinson No.33H fulfills that commandment better than any other electronic component I’ve ever heard (and, of course, I’ve never heard the No.33s). You can’t come any closer to the sound of “no amplifier” than a pair of these babies.

The ’33H carries a price sticker that leaves me gasping—as much as I covet a pair, I know I’ll never be able to afford them. They’re also big, and can gulp down more power than many wall outlets can supply. But if you can afford them, I suggest you try them. If you can resist them, you have far more self- control than I pretend to.

Besides, you owe it to yourself to experience something this near perfection.

Description

Finally, the big Levinson is a powerhouse of an amplifier, comfortably exceeding its rated power. Specified at 150W into 8 ohms, it actually didn’t clip (defined as 1% THD+N) into that load until 265W (24.2dBW)! And the wall AC supply, at 114.5V, was starting to droop—this means that, with its own dedicated 30A line,

this amplifier will probably put out 300W into 8 ohms.

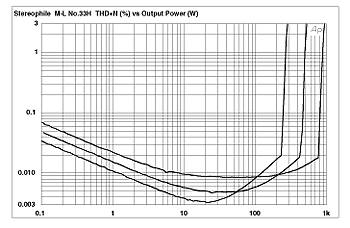

Fig.8 Mark Levinson No.33H, distortion (%) vs output power into (from bottom to top): 8 ohms, 4 ohms, and 2 ohms.

Into 4 ohms, the maximum output power almost doubled, to 500W (24dBW); into 2 ohms, 900W was available (23.4dBW). (The wall AC voltages for these power figures were 113.3V and 112.5V, respectively.) As we don’t have a dummy 1 ohm resistive load capable of sinking the almost 2kW that the Mark Levinson is presumably capable of putting out into this load, I wasn’t able to check its clipping power into 1 ohms. However, the fractional decibel drop in dBW each time the load is halved suggests that this amplifier behaves as an almost perfect voltage source.—John Atkinson

Specs:

Solid-state monoblock power amplifier.

Rated continuous-power outputs:

150W into 8 ohms (21.8dBW),

300W into 4 ohms (21.8dBW),

600W into 2 ohms (21.8dBW), 1

200W into 1 ohm (21.8dBW).

Frequency response: 20Hz-20kHz,

<0.5% THD.

S/N ratio: better than 80dB (ref. 1W), better than 105dB (ref. full output).

Input impedance: 100k ohms balanced, 50k ohms unbalanced.

Output impedance: <0.05 ohms, 20Hz-20kHz.

Damping factor: greater than 800 at 20Hz.

Input sensitivity: 130mV for 2.83V output, 1.59V for full-rated output.

Voltage gain: 26.8dB.

Typical power consumption: 540W ±5% at idle, 210W ±5% in standby.

Mains voltages: 100V, 120V, 200V, 210V, 220V, 230V, or 240V AC mains operation at 50 or 60Hz, set at factory.