Revel Ultima Salon2 Speakers

Original price was: R550,000.00.R155,000.00Current price is: R155,000.00.

When I’d reviewed my first pair of Salon2s, for the June 2008 Stereophile, I’d described it as “a new reference standard in floorstanding loudspeakers that has earned my strongest recommendation.” The Salon2 went on to be listed in Class A (Full Range) of Stereophile‘s “Recommended Components,” and was named Stereophile‘s Component of the Year and Joint Loudspeaker of the Year for 2008. But its Class A status expired after 2012—listings in “Recommended Components” do not remain active for more than three years unless at least one of the magazine’s contributors has had continued experience in that time. So John Atkinson suggested that I write this Follow-Up, which evaluates whether the design’s reputation has survived the test of time.

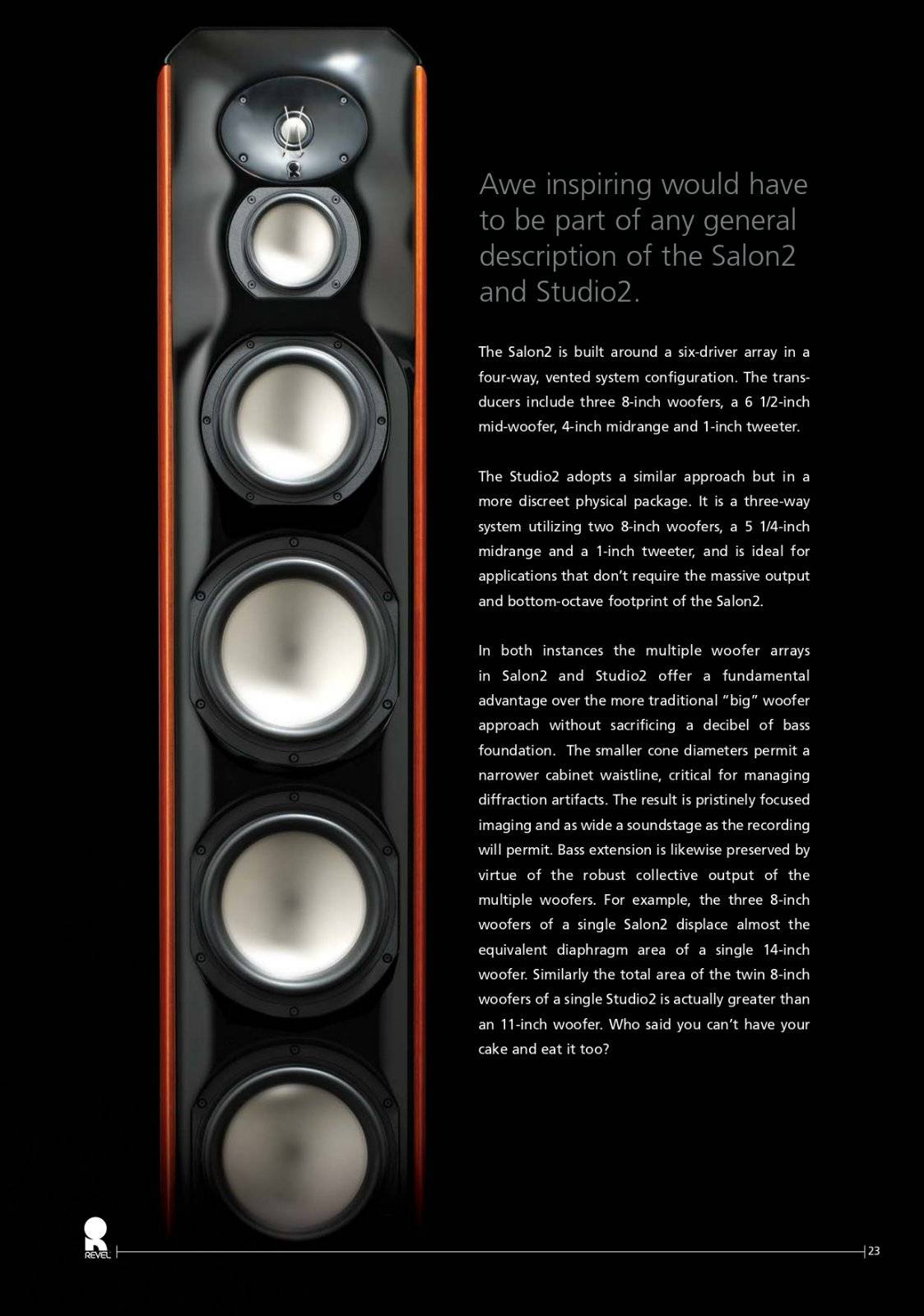

The Salon2 continues to be Revel’s biggest tower loudspeaker, measuring 53″ tall by 14″ wide by 23″ deep and weighing 146lb. Its vented cabinet houses three 8″ woofers, a 6.5″ midwoofer, a 4″ midrange, and a 1″ beryllium-dome tweeter, and its fourth-order crossover filters are set to 150Hz, 575Hz, and 2.3kHz. Revel specifies the Salon2’s frequency response as 23Hz–45kHz,±3dB. The speaker can be adjusted for position-related room-acoustic effects by using the Low Frequency Compensation and Tweeter Level dials on its rear panel.

My 2008 review of the Salon2 was conducted in my former listening room, which measured 25′ by 13′, with a 12′-high semicathedral ceiling. The loudspeakers were positioned 6.5′ from the front wall, 3′ from each sidewall, 7.5′ apart, and 7.5′ from my listening chair. JA measured their frequency response in my room by taking ten 1/6-octave–smoothed spectra for each speaker individually in a rectangular grid 40″ wide by 18″ high and centered on my ears in my listening chair. As he stated in his Measurements section, the results showed “an extraordinarily smooth, flat response… [that] offers full output down to below 20Hz.”

Now the Salon2s reside in my new, 143-square-foot listening room in California. I placed them to either side of my equipment rack and 2.3′ from the front wall, 6.3′ apart (measured from the centers of the tweeters), and 6.3′ from my listening chair. Pink-noise tests in my new room revealed minor changes in treble balance during the “sit down, stand up” test. Richard Lehnert’s voice on John Atkinson’s Editor’s Choice test CD (Stereophile STPH016-2) sounded natural, with none of the chestiness I’d heard in the first part of my original review.

Because JA, for his March 2009 Follow-Up on the Salon2s, had measured their spatially averaged room response at the listening positions in both his and my old listening rooms, I was curious to repeat those measurements in my new room, using different measuring hardware and software. As he had, I averaged ten 1/6-octave–smoothed spectra for each speaker individually in a rectangular grid 40″ wide by 18″ high and centered on the positions of my ears. (I now sit 6.3′ from the speakers, not 7.5′, as before.) I used a Studio Six iTestMic2 and their AudioTools FFT module (v.10.7.11) running on my Apple iPhone 6. The Salon2’s bass response extends well below 20Hz, ±5dB, and rolls off gradually above 12kHz, perhaps due to the room’s furnishings. As in prior measurements, the Salon2s’ Tweeter Level controls were set to “0” (flat).

The modes of JA’s listening room elevated the Salon2s’ bass response between 15 and 35Hz. A similar mild boost occurred in my new California room between 25 and 40Hz, a region to which the Salon2s’ downfiring ports contribute. The response between 50 and 100Hz wasn’t as smooth as in JA’s room. I tried to use the speakers’ Low Frequency Compensation switches to smooth out this region. Switching them from Normal to Contour reduced the impact of percussion and shrank the bloom and rumble of organ-pedal notes. Switching to Boundary—a setting intended to be used when the Salon2 is less than 2′ from a sidewall—reduced the bass output too much for my taste. Using AudioTools’ FFT room-response spectral analysis, I measured a 5dB drop in output below 100Hz. Kevin Voecks confirmed my findings with plots taken in an anechoic chamber that showed a 2dB reduction in output under 300Hz with the Contour setting and a 5dB reduction with the Boundary setting. I found Normal best for percussion sounds, and for orchestral and pipe-organ music in general. Based on the rolloff above 12kHz, I left the Tweeter Level dial at +1dB for my listening sessions. The settings evaluated, I turned from uncorrelated pink noise to music.

I was impressed with the Salon2’s extraordinary bass response. While a pair of MartinLogan 800X subwoofers (10″ drivers) and my Quad ESL-989 speakers could deliver deep bass, rattle objects, and mildly pressurize the room, the Salon2s delivered weightier and better-defined bass, with greater extension, in the final, 25Hz-anchored organ-pedal chord of James Busby’s performance of Herbert Howells’s Master Tallis’s Testament, from the compilation Pipes Rhode Island (CD, Riago CD-101). The Salon2s are the only loudspeakers I’ve heard deliver the mass, solidity, tension, and pressure I’ve felt from actual organ-pedal notes in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, in upper Manhattan. “Why So Serious,” from Hans Zimmer and James Newton Howard’s film score for The Dark Knight (CD, Warner Sunset 49860-0), presented a solid, crushing 24.9Hz synth note that seemed to pull all the air out of the room.

This ability to play at high levels throughout the low-frequency range enhanced recordings of orchestral music, making them intensely compelling and involving, as if I were hearing them for the first time. A vinyl recording of Erich Leinsdorf conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra in excerpts from Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet (direct-to-disc LP, Sheffield Lab 8) was no exception. Although I’ve played this recording innumerable times, I hadn’t been aware of the immense space occupied by the orchestra, or of the power of the driving rhythm in the double basses. Similarly, the fortissimo bass-drum strokes in the second section of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps, in the recording by Esa-Pekka Salonen and the LAPO (SACD/CD, Deutsche Grammophon 000718236), seemed to spring forth from the floor, perhaps as a result of the Salon2s’ downfiring ports.

My recent experiences confirm the Salon2’s ability to resolve fine details in recordings. It reproduced the subtle differences between venues and the strengths of piano keystrokes in two recordings of J.S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations—by Glenn Gould, 1981 (CD, CBS Masterworks MK 37779), and by Simone Dinnerstein, 2005 (CD, Telarc CD-80692)—and differentiated individual voices of singers in the Portland State Chamber Choir as they sang Eriks Esenvalds’s The First Tears (24/88 WAV from CD, Naxos 8.579008), the voices arrayed across a wide soundstage. Bass lines formerly buried in ensemble pieces were clearly revealed by the Salon2s—eg, Tim Schmit’s bass guitar underpinning the vocalist in “Hotel California,” from the Eagles’ Hell Freezes Over (CD, Geffen GEFD-24725), or Jerome Harris’s acoustic bass-guitar line in Duke Ellington’s “The Mooche,” from Rendezvous: Jerome Harris Quintet Plays Jazz (CD, Stereophile STPH013-2), a recording engineered, edited, and mixed by John Atkinson.

The Salon2s also made differences between components startlingly audible. The Constellation Inspiration Stereo 1.0 amplifier became harsh, edgy, and zippy when paired with Bryston’s BP-173 line-level preamplifier, but was far smoother and more transparent with Bryston’s own BP-26 preamp with MPS-2 power supply. Similarly, the Mark Levinson No.534 power amplifier sounded flat and unexciting with the Bryston combo of BP-26 and MPS-2, but came to life with the BP-173, its sound blossoming with transparency, clear highs, and bold dynamic contrasts.

In summary, 10 years on, Revel’s Salon2 continues to impress me with, as JA wrote in 2009, “a resolution of fine detail [that] is rare among loudspeakers,” an “ability to play at high levels with full-range low frequencies,” “a neutral, uncolored midrange,” “superbly well-defined and stable stereo imaging,” “silky-smooth highs courtesy its beryllium-dome tweeter,” and “sonic coherence from bottom to top of the audioband.” For all of those reasons, it remains my reference loudspeaker.—Larry Greenhill

John Atkinson wrote about the Ultima Salon2 in March 2009 (Vol.32 No.3):

When, in June 2008, Larry Greenhill reviewed Revel’s top-line loudspeaker, 3 the four-way Ultima Salon2 ($22,000/pair), he concluded that “In the Salon2, Kevin Voecks and his team have produced far more than a cosmetic upgrade of the Salon1. They have created a new reference standard in floorstanding loudspeakers that has earned my strongest recommendation.”

I gave the Ultima Salon2s a listen when I drove up to Larry’s to measure them in his room, and yes, they did indeed seem to be something special. After Larry’s review had been prepared for publication, I asked Revel’s Kevin Voecks if I could borrow a second pair, in order to do some listening for myself. LG’s samples were serial numbers 0343 and 0344, mine 0511 and 0512. The Salon2s replaced my regular speakers, the PSB Synchrony Ones, which I reviewed in April 2008, and followed the Esoteric MG-20s, which I wrote about in August 2008. I spent a couple of weeks getting familiar with the big Revels’ sound—setup was straightforward, other than the usual difficulties of handling such a large, heavy speaker; with its tall, slender shape, the Salon2 looks smaller than it really is. (The supplied carpet-piercing spikes were mandatory at helping keep the powerful bass region under control.) However, I then had to put the Revels to one side while I reviewed Dynaudio’s 30th Anniversary Sapphire loudspeaker (January 2009).

Going back to the Revels, it was immediately evident that, as much as I’d enjoyed my time with the Sapphires, the Salon2s were larger speakers in every way: more extended, more powerful-sounding low frequencies, an enormous and stable soundstage, and considerably greater dynamic range. In fact, in the Salon2’s ability to play at very high levels without strain or noticeable compression, it was the equal of the very impressive and similarly priced KEF Reference 207/2, which I reviewed in February 2008.

Today’s popular music tends to go over my head—even more than before, with the major labels’ abandonment of artist development, pop comprises ephemeral music by equally ephemeral talents. But when I caught Kanye West on Saturday Night Live performing the hit “Love Lockdown,” from his album 808s & Heartbreak, it was obvious even through my TV’s tinny speakers that there was something going on. Playing the CD (Roc-A-Fella/Def Jam) through the Revels, their three 8″ reflex-loaded woofers per side driven by the 750W Musical Fidelity 750K Supercharger monoblocks, the track made musical sense. The sampled three-note bass figure that opens “Love Lockdown” needs both maximum LF extension from a speaker and the ability to play loud without the recording’s gross needs for bass reproduction muddying up the midrange. When first the pitch-corrected voice enters, then the piano riff, then the thunderous drums, each new musical element remains maximally distinct from the others and from the bass figure.

A speaker like the Salon2, which could handle this Kanye West track at room-filling levels, is cruising with classical. But even after I’d gotten used to the Salon2s’ ability to fill my listening room with sound, it was their retrieval of fine details that continued to impress. An example: Last May I recorded Minnesotan vocal group Cantus in concert, performing covers of pop songs, for release next summer. As you can read in producer Erick Lichte’s Follow-Up on the Musical Fidelity 550K amplifier, this was not a purist recording. I used close mikes on all the singers and percussion instruments, and took direct electronic feeds from the Yamaha keyboard and Rickenbacker bass guitar.

Erick and I were working on the provisional mixes last fall, monitoring with the Revel Salon2s, and it was apparent that for the concert’s opener, Curtis Mayfield’s “It’s All Right,” we needed to add some mild equalization to the five vocal tracks in order to compensate for the cardioid mikes not being quite close enough to give the full proximity effect demanded by this kind of music. I dialed in +3dB in the upper bass for each of the vocal tracks and Erick gave a listen.

“Something’s not right,” he said. “Did you apply the EQ to the second tenors?”

I looked at the settings. Under pressure to work fast, I had applied the EQ to just four of the five vocal tracks. The second tenor track was indeed playing back flat.

Such resolution of fine detail is rare among loudspeakers. That the Salon2 can offer such resolution along with the ability to play at high levels with full-range low frequencies, and has a neutral, uncolored midrange, and offers superbly well-defined and stable stereo imaging, and has silky-smooth top octaves courtesy its beryllium-dome tweeter, and features sonic coherence from bottom to top of the audioband, makes it both a Class A speaker in Stereophile‘s “Recommended Components” listing, and gave me no choice but to make it my “Editor’s Choice” for Stereophile‘s 2008 Component of the Year. And enough of the magazine’s reviewers agreed with me that the Salon2 was also voted Joint Loudspeaker of 2008.

A full set of measurements for the Ultima Salon2 can be found here. But as I had measured the Salon2s’ spatially averaged response at the listening position in Larry’s room, I thought it would be instructive to repeat those measurements in my room.

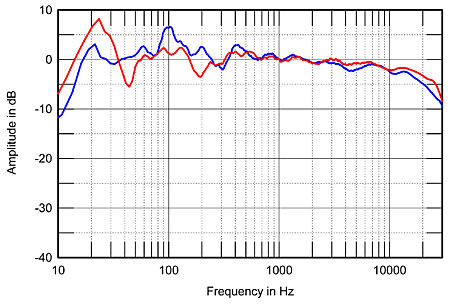

Fig.1 Revel Ultima Salon2, spatially averaged, 1/6-octave response in LG’s listening room (blue), JA’s listening room (red).

In both cases, I took ten 1/6-octave–smoothed spectra for each speaker individually in a rectangular grid 40″ wide by 18″ high and centered on the position of the listener’s ears. (LG and I both sit 10’/3m away from the speakers.) I used an Earthworks omni microphone and a Metric Halo ULN-2 FireWire audio interface, in conjunction with SMUGSoftware’s Fuzzmeasure 2.0 running on my Apple laptop. The results are shown in fig.1, the blue trace being the spatially averaged response in LG’s room, the red trace the response in my room. The differences in the traces below 300Hz are due to the different effects of low-frequency resonant modes in the two rooms that have not been minimized by the spatial averaging. But above 300Hz, the traces are both extraordinarily smooth and flat and almost precisely overlay one another, at least up to 10kHz, where my room’s smaller size and less-absorptive furnishings result in slightly more top-octave energy. (The Salon2’s treble control was set to its flat position for both responses.)

At the other end of the spectrum, the speaker’s output extends to below 20Hz in both rooms, but because I could not get the Revels as far from the room boundaries as Larry can in his larger room, there is a boost apparent between 15 and 35Hz in my room (red trace), which basically corresponds to the region handled by the Salon2s’ large, downward-firing ports. On the other hand, the speakers’ response in LG’s room (blue trace) is not as smooth in the upper bass as it is in my room.

With the Ultima Salon2, Revel’s design team has taken the conventional concept of a moving-coil box loudspeaker to the limit of what is currently possible. As Larry Greenhill wrote, “a new reference standard in floorstanding loudspeakers.” Indeed!—John Atkinson

Back in March 1998, Revel’s Ultima Salon1 floorstanding loudspeaker generated quite a stir at Stereophile (Vol.22 No.3). Our reviewers were impressed by its seven designed-from-scratch drive-units, its ultramodern enclosure with curved rosewood side panels, exposed front tweeter and midrange, rear-facing reflex port and tweeter, and a flying grille over the mid-woofer and woofers. In the December issue (Vol.22 No.12), the Ultima Salon1 ($16,000/pair) was named Stereophile‘s “Joint Speaker of 1999” for its “big bass, timbral accuracy, low distortion, dynamics, lack of compression, and best fit’n’finish.”

Not everyone shared this enthusiasm, finding the Salon1’s Bauhaus aesthetic too industrial-looking. The speaker’s 240-lb shipping weight, 51″ height, and 30″ depth also presented distinct challenges in placement and décor. Evidently, Revel listened—the Ultima Salon2 is slimmer, taller, and lighter.

What’s the Same

The Salon1 and Salon2 are both tall, heavy, floorstanding, four-way, ported dynamic loudspeakers bristling with Revel-designed drivers: a 1″ dome tweeter, a 4″ inverted titanium-dome midrange unit, a 6.5″ midwoofer, and three 8″ woofers. Their enclosures are constructed from 45mm-thick, nine-layer MDF molded into a gracefully curved form. Then, instead of the flat front panel and mitered sides of a typical box speaker, a thick, curved front baffle designed to minimize cabinet resonances is attached.

For each Salon, the goal was the same: achieve an off-axis response that closely matches the on-axis response. To this end, both speakers have: steep, fourth-order (24dB/octave) crossover slopes to prevent the distortions that occur when drivers work outside their optimal ranges; small midrange drivers; a relatively low tweeter crossover frequency; crossover components matched to within 0.5dB of the original reference prototype; and curved front baffles to minimize diffraction effects.

What’s New

To create the Salon2, Revel put the Salon1 on a diet, morphing it into a slim, oval column that’s 2.3″ taller, 3″ narrower, 7″ shallower, and 72 lbs lighter than its predecessor. Gone are the Salon1’s heavy side panels of rosewood veneer, separate head baffle, rear reflex port, and rear tweeter. Instead, the rear of the Salon2 is a smooth curve. The speaker-terminal panel is now covered by a door of smoked plastic. The curved front baffle is black, and the recessed drivers are now free of external mounting hardware. A new, magnet-fastened, black grille covers all six drivers.

The Salon2’s Revel-designed midrange drive-units use titanium diaphragms, this material chosen for its greater tensile strength. Dual motor pole-pieces are placed between two inverted and opposing neodymium magnets centered inside each voice-coil, to increase magnetic performance; smaller magnet/motor structures provide more usable internal speaker volume; new aluminum flux-stabilization rings further minimize flux modulation to reduce second-harmonic distortion; oversized voice-coils—2″ for the woofer, 1.5″ for the midrange—maximize output and minimize dynamic compression; and vent holes have been cut through the motor’s pole and shield cup to remove trapped heat from inside the woofer’s motor and reduce air noise inside the voice-coil.

The Salon2 has a tweeter with a beryllium dome, which has a low density but a high stiffness. These qualities push the tweeter dome’s first breakup mode above 50kHz—twice as high as that of the Salon1’s aluminum-dome tweeter—with usable frequency response up past 40kHz. A unique pin at the back of the tweeter’s rear cavity helps break up standing waves, while a copper cap on the tweeter’s pole-piece reduces inductance modulation and the corresponding harmonic distortion.

The tweeter is mounted in a shallow 4″ by 5.5″ waveguide, formed in the front baffle, that matches the tweeter’s directivity to that of the midrange’s at the crossover frequency. It also adds 3–7dB more gain around and above the crossover region, and reduces the tweeter’s directivity above 9kHz. Because all of this increases the tweeter’s output by 2dB, Revel decided that the Salon1’s rear tweeter would not be needed in the Salon2.

The Salon2’s woofers use aluminum cones rather than the Salon1’s mica/carbon-filled copolymer cones, and are reflex-aligned with a hyperbolic, downward-firing, 16″ by 4″ port with an asymmetrical flare rate, to eliminate “chuffing” noise when the speaker is driven at high levels. The tunnel’s tapered shape “behaves as if it is longer than a straight ducted port,” according to Revel.

The use of separate filter boards for each of the crossover’s four frequency ranges is said to prevent distortion-causing magnetic interference. Connections soldered point-to-point and large, air-core inductors are used on each board. The two pairs of heavy, gold-plated binding posts are mounted in a cast-aluminum panel set into a shallow depression cut into the Salon2’s curved back. The hollowed-out posts accommodate spade lugs as well as speaker-cable plug adapters. Dual pairs of posts mean that the Salon2 can be driven by two stereo amplifiers (ie, biamplified) or with double speaker cables (ie, biwired). The owner’s manual clearly explains these setups. If the owner prefers a more conventional arrangement of one stereo power amp and two pairs of speaker cables, two accessory jumper straps (supplied) connect the posts of the upper and lower drivers.

The Salon2’s terminal panel is covered by a door of smoked plastic to maintain the enclosure’s curved exterior. This door is too small and light to generate sonic disturbance when the speaker is playing, but the channel at the door’s bottom proved too narrow for my speaker cables. As a result, I had to leave the door open.

The Salon2’s terminal panel has two rotary controls for adjusting Tweeter Level and Low-Frequency Compensation. The Tweeter Level control offers five positions: 0, and ±0.5 and ±1.0dB. The Low-Frequency Compensation control has three settings: Contour produces a small (–1.5dB) but audible bass cut from 30 to 50Hz, to deal with standing-wave effects in the room; Boundary reduces the bass response by 5dB from 30 to 50Hz, to compensate for placing the speaker very close to a wall or building it into some sort of enclosure; Normal is for the optimum free-space placement.

Like the Salon1, the Salon2 is of superb quality in its fit’n’finish. Although a speaker binding post on one of my review samples arrived loose, designer Kevin Voecks assured me that it could be fixed in the field without the owner having to ship the speaker back to the factory. Each Salon2 is shipped with four combination metal spikes/glides, which screw into the cabinet bottom and are secured with a metal locking ring set off by a felt washer, to protect the speaker’s finish. Because my hardwood floors are finished, I didn’t use these. I found the Salon2’s gold-plated hardware and connections to be sturdy and easily accessible; they should last a lifetime.

Setup

Setup

I left the Ultima Salon2’s grilles on for all the listening. I first placed the speakers in the positions where my Quad ESL-989s work best: 3′ out from the sidewall, 3′ from the front wall, and facing the full length of my listening room. This location lent some chestiness to Richard Lehnert’s voice on Editor’s Choice (CD, Stereophile STPH016-2). Setting the Salon’s Low-Frequency Compensation to Contour didn’t improve the situation, while the Boundary setting just thinned out the middle tones of his voice. Moving the Salon2s farther out into the room—80″ from the front wall, 50″ from the sidewalls, 58″ apart, and 90″ from my listening chair—helped Richard’s voice sound more natural and clean (footnote 1). This allowed me to leave the speakers’ bass tone controls in their Normal position for most of my listening sessions.

After some experimentation, I set the Tweeter Level to flat (“0″). At 48″ from the floor, the Salon2’s tweeter is higher than the 38” my ears are from the floor when I sit down. Even so, the Salon2’s treble balance with pink noise didn’t change during the “sit down, stand up” test. Final adjustments included phase checks, low-frequency warble test tones, comparative nearfield (8′) and farfield (16′) listening, and positioning the speakers for optimal soundstaging and imaging using the pink-noise tracks from Editor’s Choice.

I drove the Salon2s with various solid-state amplifiers, including a Mark Levinson No.334 (125Wpc into 8 ohms), a Krell FPB-600c (600Wpc into 8 ohms), and Bryston 28B-SST monoblocks (1300W into 8 ohms). The ML No.334 demonstrated impressive dynamics, playing huge deep-bass transients from synthesizer music, sustained organ-pedal chords, and bass-drum notes at high volumes. The Krell FPB-600c seemed to have limitless deep-bass extension. And the Bryston 28B-SSTs drove the Salon2s to 105dB peak levels (at 8′) with no evidence of distorting.

Sound

I expect good deep bass from a floorstanding, full-range loudspeaker, and the Salon2 did not disappoint. It reached down to 17Hz with no more than ±3dB variation from its output at 100Hz, with no sign of doubling (ie, no second-harmonic distortion). This was the deepest bass I’ve ever gotten in my listening room from a full-range floorstander. (See fig.8 in JA’s “Measurements” sidebar.)

I confirmed the Salon2’s deep-bass extension by listening to the low-frequency warble tones on Editor’s Choice, which were clearly audible and pitch-perfect down to the 25Hz 1/3-octave band. I felt some useful output as low as 20Hz, and so did my house—the baseboard radiator panels at the other end of the room began to dance and rattle. The chromatic-scale half-step sinewaves on track 19 were reproduced cleanly and evenly, particularly the 130.8Hz note, which falls near the crossover of the Salon2’s midbass and woofers.

To confirm this superb low-bass extension, I turned to music. Organ recordings were enhanced and clarified by the Salon2’s deep-bass extension. The speaker’s three woofers produced a solid 32Hz tone that reproduced the low pedal C that ends Herbert Howell’s Master Tallis’s Testament, from the Pipes Rhode Island collection (CD, Riago 101 (footnote 2)). Additionally, the Salon2 made it easier than ever before to follow bass lines. Whether it was Tal Wilkenfeld’s intricate and tuneful electric-bass line on “Truth Be Told,” from her Transformation (CD, Goldelux Productions TAL001-2), downloaded from iTunes and played via WiFi from my Slim Devices Squeezebox; or Jerome Harris’s careful bass work weaving in and out of his quintet’s performance of “The Mooche,” from Rendezvous (CD, Stereophile STPH013-2), I heard none of the tendency to blur bass notes that I’ve heard from other speakers. The Ultima Salon2 played percussion and/or piano and/or brass with full impact while retaining complete clarity of the softer bass lines.

The fortissimo bass-drum strokes heard in the second movement of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps, in the recording by Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic (SACD, Deutsche Grammophon 000718236), burst into my listening room as sudden, well-defined thuds with cleanly defined leading edges and sudden, explosive power. These bass-drum strokes seemed to spring forth from the floor, even though the clean deep-bass pitch was actually too low to be directional. The Salon2s’ downward-firing ports must have activated my wooden floor, which added to the drum note’s power, slam, solidity, and weight. However, there were no lingering overtones, no overhang, and no disturbance of the midrange or treble sounds. Nor did the Salon2s’ woofers evince any compression during the sustained bass notes of “First Haunting/The Swordfight,” from James Horner’s score for Casper (CD, MCA MCAD-11240).

The Salon2’s midrange and treble showed the greatest differences in direct comparisons with the Salon1. The Salon2 had less emphasis in the presence region, but the pair of them didn’t produce as much air and soundstage depth, perhaps due to the removal of the Salon1’s rear tweeter. However, the Salon2’s midrange and treble showed greater top-to-bottom transparency than the original Salon. While the Salon1 continued to impress with its bass power, speed, and rear-tweeter ambience and air, the Salon2 seemed to be more relaxed and more neutral, with greater overall transparency. Both had deep bass to spare, but the Salon2’s response in this region seemed more effortless and smooth, with even less dynamic compression than the Salon1.

The Salon2’s midrange and treble improvements were best heard with piano recordings. I was delighted to hear natural resonances and tonalities that greatly added to my involvement in the music—greater clarity, increased coherence, and more emotional impact, from a variety of piano-music genres. For example, the Salon2 communicated the striking dynamics and controlled power of Variation 1, from Glenn Gould’s 1982 recording of J.S. Bach’s The Goldberg Variations (CD, CBS Masterworks MK3779), which contrast strongly with the lyrical, deliberate moodiness of Simone Dinnerstein’s recent, award-winning recording (CD, Telarc CD-80692). The light, joyous character of Keith Jarrett’s piano on his The Carnegie Hall Concert (CD, ECM 1989/90) was strikingly evident. Timbral qualities I heard during a live recital by pianist Leif Ove Andsnes were also heard in his recent recording with the Artemis Quintet of Brahms’s Piano Quintet in f (CD, Virgin Classics 395143 2).

Footnote 1: The Salon2’s manual gives great advice for placing the speakers in the room, suggesting that the buyer move “the loudspeakers further from the front and side listening room walls to improve stereo imaging and sense of spaciousness in the listening room.” It also states that “a coffee table between the speakers and the primary listening position will degrade imaging and timbre.” For that reason, I moved a marble table from the back of my listening room outside to the patio.

Footnote 2: John Marks, who played a key role in recording Master Tallis’s Testament, reports “that the Low C was a 16-foot pipe playing 32Hz as the fundamental, a 32-foot pipe playing 16Hz as the suboctave support, and at least one 8-foot stop providing harmonics at 64Hz.”

I also heard what Anthony Tommasini of the New York Times called “explosive lyricism, surging power, and incisive attack” from pianist Yundi Li’s recording of Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto 2, with Seiji Ozawa and the Berlin Philharmonic (CD, Deutsche Grammophon 001017502). And I enjoyed the natural balance of bass weight, treble control, and slight reverberation in pianist Robert Silverman’s recording of Liszt’s Liebestraum.

Vocal recordings were rendered with outstanding timbral accuracy and stunning realism. The Salon2 captured a smoothness and lyricism in tenor Albert Jordan’s version of Smokey Robinson’s “Who’s Lovin’ You?” on Cantus (CD, Cantus CTS-1207), that I’d never heard before. Harry Connick, Jr.’s rich baritone singing “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” from the When Harry Met Sally . . . soundtrack (CD, Columbia CK 45319), was as natural and realistic as I’ve heard it, with none of the honk, midbass emphasis, or closed-in quality I’ve heard from lesser speakers.

The Salon2s delivered a deep, broad, rock-solid image of the soundstage, projecting a solid, three-dimensional image of the full choir, powerful organ, and harp on A Gaelic Prayer, from John Rutter’s Requiem (CD, Reference RR57-CD)—as well as a sonic image of the choir that hovered suspended, deep offstage, behind the voice of tenor José Carreras on the Kyrie from Ariel Ramirez’s Misa Criolla, conducted by José Luis Ocejo (CD, Philips 420 955-2).

Like the Salon1 before it, the Salon2 had outstanding timbral accuracy that allowed me to hear subtle qualities of male vocalists in choirs, the reediness of wind instruments, and the sounds of drum rims and soundboards. I noticed a series of distinct resonances in the male chorus singing “Lord Make Me an Instrument of Thy Peace,” from Rutter’s Requiem, and the solo bassoon that opens Le Sacre du Printemps was unusually rich, sweet, and captivating.

The Salon2 demonstrated jaw-dropping dynamics in my listening room. I heard no grain or compression until the amplifier ran out of steam. The Salon2 played synthesizer and bass-drum crescendos so well that I kept cranking up the volume. David Hudson’s raw, pulsing, raspy, bass-didgeridoo version of “Rainforest Wonder,” from his Didgeridoo Spirit (CD, Indigenous Australia IA2003 D), and the thudding, sledgehammer-like bass synth in “Assault on Ryan’s House,” from James Horner’s Patriot Games soundtrack (RCA 66051-2), hit exceptional peak SPLs, but the Salon2 refused to choke. The Stravinsky recording thrilled me, especially when the wind instruments joined the thunderous stomping of strings used as percussion. The Rite‘s pulsing tempo and surging energy built through Adoration of the Earth, near the end of Part 1, then erupted into the explosive Dance of the Earth. The Salon2 possessed all the power, range, and pitch definition I’ve heard from the best powered subwoofers. I let up only when the Krell FPB-600c blew my house’s circuit breakers.

The Ultima Salon2 remained in complete control, falling silent after each percussion note. Cymbals sounded startlingly clear, utterly transparent, and sweet—as in the opening of “The Mooche,” from Jerome Harris’s Rendezvous, and Patricia Barber’s “Noxus,” from Café Blue (SACD, Premonition/Blue Note/Mobile Fidelity UDSACD 2002). The Salon2s had a spatial precision that I normally associate only with my Quad ESL-989 electrostatic speakers. Nor was the Revel’s ability to deliver large, even amounts of sonic power into my listening room done at the expense of the most subtle musical details. After I pointed out, to the usually taciturn John Atkinson, the utter clarity of Jerome Harris’s soft bass-guitar line in “The Mooche”—JA had been the recording engineer for Rendezvous—I heard him whisper, “These are very good loudspeakers, Larry.” The resolution with which this subdued bass line was being presented struck us both as most impressive, especially coming from 178-lb, floorstanding, full-range, dynamic speakers.

Summary

While I find the sounds of Revel’s Ultima Salon1, the Quad ESL-989, the Burmester B-99, and the Dynaudio Evidence Master to be still among my favorites, the Revel Ultima Salon2 is the best-performing, most natural-sounding full-range loudspeaker I have auditioned in my listening room since I started writing for Stereophile in 1984. The Revel design team has smoothed the Salon1’s upper midrange while retaining that award-winning speaker’s powerful bass extension, timbral accuracy, and superb dynamics. The result is an open and transparent top end, an utterly neutral and grain-free midrange, and bass that is extended and pitch-perfect. The Ultima Salon2 does all this while sounding completely neutral, with top-to-bottom smoothness, coherence, and remarkable resolution of detail.

While $22,000/pair is a lot of money, the quality of this loudspeaker equals that of others costing up to three times as much. In the Salon2, Kevin Voecks and his team have produced far more than a cosmetic upgrade of the Salon1. They have created a new reference standard in floorstanding loudspeakers that has earned my strongest recommendation.

Description

| Frequency Response | 3 dB from 23 Hz to 45 kHz ±0.5 dB from 29 Hz to 18 kHz ±1.0 dB from 26 Hz to 20 kHz |

|---|---|

| Height | 53.3″ (135.4 cm) |

| Width | 14″ (35.6 cm) |

| Depth | 23″ (58.4 cm) |

| Weight | 146 lb (66.3 kg) Shipping weight 178 lb (80.7 kg) |

| Crossover Frequencies | Four-way, high-order acoustic response @150 Hz, 575 Hz, and 2.3 kHz |

| Finishes | Piano black or mahogany finish |

| High Frequency Driver Components | 4″ (10 cm) titanium cone midrange |

| Nominal Impedance | 6 ohms (nominal) 3.7 ohms (minimum @ 90 Hz) |

| Low Frequency Extension | 10 dB at 17 Hz -6 dB at 20 Hz -3 dB at 23 Hz |

| Low Frequency Driver Components | Three 8″ (20 cm) titanium cone woofers |

| Mid-frequency Driver Components | 6 ½” (16.5 cm) titanium cone mid-woofer |

| Sensitivity | 86.4 dB SPL with 2.83 V @ 1m (4 pi anechoic) |

| Ultrahigh-frequency Driver Components | 1″ (2.5 cm) beryllium tweeter |