Mark Levinson 331 Stereo Power Amplifier

Original price was: R120,000.00.R33,000.00Current price is: R33,000.00.

The No.331 is the latest iteration in a series of Mark Levinson 100Wpc, solid-state, stereo power amplifiers. Extensive cosmetic alterations, internal structural changes, and new circuit designs make it quite different from the No.27 and No.27.5 models that preceded it. These design refinements emanate from Madrigal Audio Laboratories’ latest flagship amplifier, the $32,000/pair, 300W RMS Mark Levinson No.33 Reference.

The earlier No.20-series Mark Levinson stereo amplifiers were based on the company’s former Reference monoblock, the $14,950/pair 100W RMS No.20 amplifier, first introduced in 1986 and brought to final “20.6” level in 1992. I reviewed the No.27 back in 1990 (Vol.13 No.6 with measurements in Vol.13 No.7). Costing $3795 at the time, this amplifier featured a combination of smooth midrange, excellent imaging, and a light, highly defined, transparent treble. The No.27’s treble and midrange sweetness offset the treble dryness in the Quad ESL-63 electrostatics I use for reference speakers, so I purchased the No.27 review sample. Even so, it had its limitations, retaining the exclusive Mark Levinson CAMAC input connectors, requiring the company’s interconnect cables, special CAMAC-to-RCA adapters, or a re-tipping of interconnects with CAMACs. I also found it to have less apparent bass extension than did other top solid-state amplifiers in level-matched listening tests.

In 1992, the ’27 was replaced by the No.27.5 ($5495, reviewed in July 1993, Vol.16 No.7). Features included “0.5” circuit boards, 10 lbs additional weight, RCA connectors, a wider chassis and faceplate, and a $1200–higher price tag. Sonic changes included added low-frequency extension and dynamic range, but I found the Krell KSA-250 amplifier still edged out the 27.5 in gain-matched listening tests, with its greater solidity of deep bass, better control of soundstage depth, and lower-midrange forwardness.

Mark Levinson’s No.20-something amplifier series went out of production in 1994, replaced by the No.33 Reference dual-chassis monaural pair and its derivatives, the Nos.331, 332, and 333 dual-mono amplifiers. I couldn’t wait to compare the new No.331 with my vintage No.27.

What’s new externally?

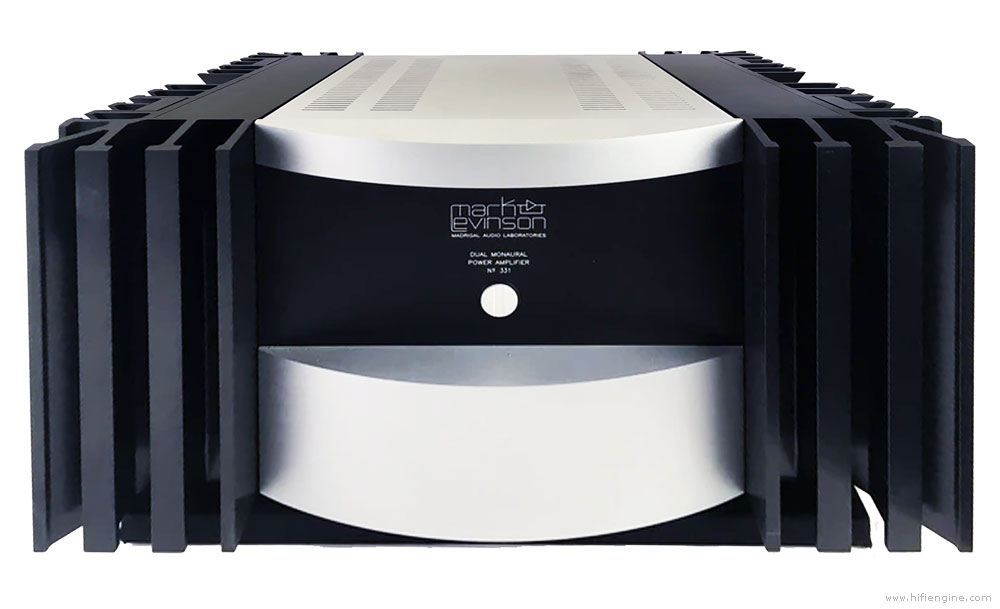

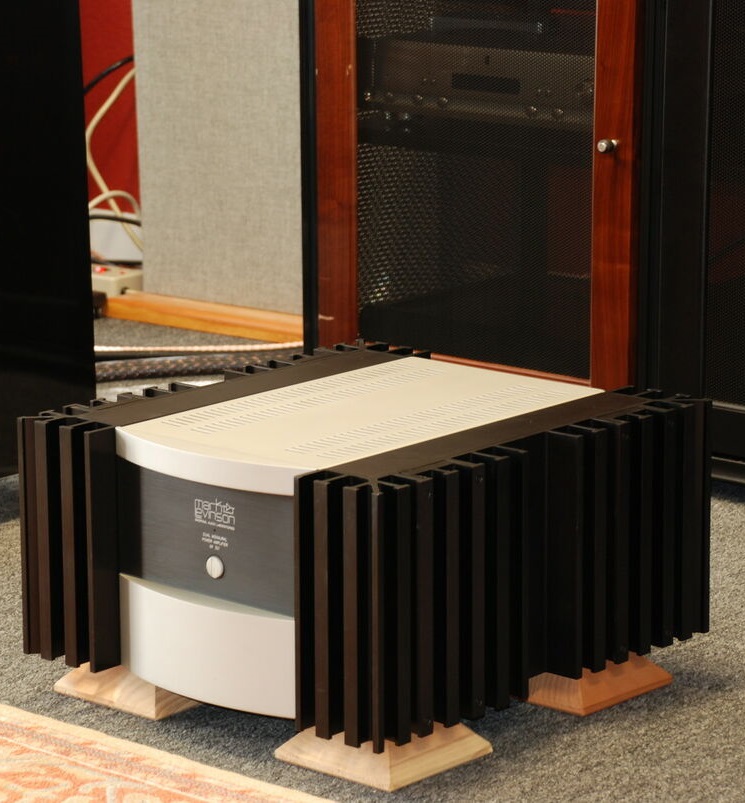

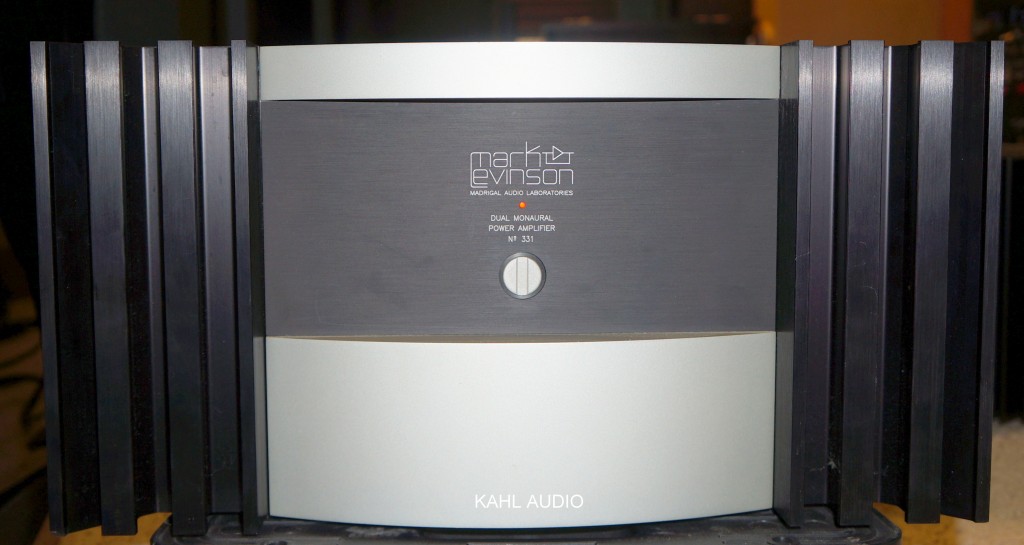

The Mark Levinson No.331 looks completely different from the 27-series amplifiers. The traditional Levinson black-cube-with-handles’n’heatsink look has been replaced with a two-tone silver and aluminum motif based on the styling of the No.33. The amplifier’s faceplate is now a curved and machined piece of solid aluminum. This faceplate frames a smaller black panel on which are engraved the company and product names. The silver front and top plates provide a strong visual contrast to the large black heatsinks running along each side of the amplifier. These heatsinks, designed in-house, have a higher mass and structural rigidity than former units, and a lower level of mechanical resonance than those used in the 20-series amplifiers.

The No.331 is 4″ deeper, 3″ taller, and 27 lbs heavier than the No.27. Unlike the older amplifiers, the 33x series has no handles front or rear. Although Madrigal’s Jon Herron told me that the amplifier can be hefted by one person grabbing the heatsinks, the manual wisely advises any new owner that “two strong people are required to unpack these amplifiers safely.”

The front panel features a red indicator LED and an On/Standby button, the latter providing power cycling, with turn-on circuitry powered by an independent power supply activated when the unit is plugged into an AC source. When power is applied after the heavy, detachable AC cord is plugged in, the amplifier remains off. One press of the power button puts the amplifier in standby mode, as noted by the slowly flashing indicator. This activates DC to the voltage gain-stages from a separate winding in each channel’s power-supply transformer. One must wait 10 seconds, then press the button a second time to toggle the amplifier between standby and full on. This delay, lengthier than found in most amplifiers, allows the in-rush circuitry to slowly charge the power-supply filter capacitors. An additional press of the button toggles the amplifier back into standby. To turn it full off, it’s necessary to depress the button for one second, or until the power indicator goes off.

On the rear panel, inputs are made via single-ended RCA connectors or balanced XLR connectors. The amplifier is shipped with tiny U-shaped shorting pins inserted in the XLRs to allow unbalanced use; pulling out these pins allows for balanced operation. A socket for a conventional IEC standard power cord sits at bottom center of the rear panel (footnote 1), flanked by a pair of remote turn-on input jacks for systems that don’t include a Mark Levinson No.30-series preamplifier.

Alternately, the No.331 can be controlled via separate back-panel communication ports by a “linked” Levinson 30-series preamplifier when the left port (“slave-in”) is connected to the master port of the preamplifier. This allows for remote, one-button turn-on when linked to another Mark Levinson product equipped with the appropriate software. An additional five 33x-series amplifiers can be daisy-chained from the other port (“slave-out”). These links provide for remote turn-on from the preamplifier and for the preamp to display error conditions if they should occur in the amplifiers.

The ‘331’s rear panel features four custom-made, gold-plated, high-current speaker-cable binding posts per channel in two columns, one for each channel, with two positive and two negative terminals in alternating fashion to allow for biwiring. These binding posts are the same 100-ampere–rated posts used on the No.33 Reference amplifier. This insulated connector satisfies the IEC-65 safety standard. The connector has a large curved wing nut. Using these posts, I was able to achieve tight, high-contact pressure connections with only modest finger pressure, and did not need my usual set of wrenches. These binding posts are now my favorite, easily the equal of the elegant speaker posts found on Classé amplifiers.

What’s new internally?

Whereas the No.27’s top cover was made from a single sheet of undamped sheetmetal, with countersunk holes, fastened to the chassis with 12 small Allen nuts. The top cover for the No.331 is a well-damped, lightweight, nonresonant piece of aluminum that slides into two grooves at the top of the chassis’ lateral heatsinks and is secured with only two Allen-head nuts on the rear panel.

Underneath its top cover the No.331 is a densely packaged amplifier: visual inspection revealed only a large steel tunnel running down the center of the chassis, flanked by two long printed circuit boards (pcbs). This tunnel covers the two toroidal power transformers—801VA in the ‘331 vs 729VA in the ‘27.5—toroidal transformers than found in the 20 series, and, which are mounted on their sides within the steel tunnel.

The No.331 shares many features found in earlier Mark Levinson amplifiers: dual-mono design with completely independent power supplies, voltage, and current gain-stages packaged in one compact chassis; two toroidal transformers, one for each channel, oriented to cancel stray magnetic fields; a soft-clipping circuit to reduce the subjective effects of amplifier overload and clipping; and all voltage gain-stages independently regulated. However, the current-gain output stage is unregulated; only the No.20.6 amplifier (now out of production) uses regulation for its output stage.

The ‘331 includes refinements not found in the No.20 series. First, better manufacturing and engineering technology are used in production. The No.331 utilizes “wire-free” design elements to reduce losses and nonlinear artifacts in the signal path. From the supply electrolytics to the output devices to the loudspeaker binding posts, all high-current connections are made using solid bars of oxygen-free plated copper. For voltage-gain stages, all inputs are directly soldered to their respective pcbs—and subassembly connections are made with modular connectors—to avoid the use of wire. This modular design approach reduces labor costs during manufacturing, resulting in an amplifier with improved ratings over the No.27.5 but costing about $1000 less.

Madrigal believes that these improvements in mechanical design also greatly reduce the subtle unit-to-unit sonic variations (due to different crimp pressures, different dressing of the harness, and different solder heat), reduce the number of sometimes unreliable solder connections, improve product reliability, and facilitate in-the-field service. For example, the manufacturer claims that an experienced technician using conventional tools can disassemble a No.331 completely in 15 minutes, and reassemble it in the same amount of time.

The design of the ‘331’s signal circuitry is based on the No.33 Reference amplifier. It features a balanced signal path, three voltage gain-stages, and replaces the No.27.5’s active input buffer with a different topology. This is said to yield even greater common-mode rejection performance, a better match between the inverted and non-inverted signals, lower noise, and lower distortion. An important aspect of the design was the implementation of a new sliding-bias output-stage topology which Madrigal calls “Adaptive Biasing.” The design goal was for the No.331 to function as a true voltage source for any loudspeaker load between 8 ohms and 2 ohms. (The No.33 Reference extends this ability down to 1 ohm.)

As discussed in one of the company’s white papers, an amplifier rated for this range of impedance loads needs a high level of output bias to minimize crossover distortion and to avoid any possibility of reverse-biasing an output device. In a traditional class-A design, this leads to a large quiescent current draw, hence the production of a lot of heat. Madrigal’s solution was to modulate the bias level as a function of the input signal, using an algorithm that includes both the input signal and the level of output current being demanded by the loudspeaker.

The No.331’s power supply features two triple-bypassed, 44,000µF, low-ESR electrolytic filter capacitors per channel. The intended capability to continuously deliver power ranges from 100W to 400W requires a large number of output devices to source the required current. Each channel uses 16 TO3-can bipolar transistors in matched, complementary pairs.

Protection circuitry protects the amplifier against short circuits at the speaker terminals, overheating, excessive AC supply current, AC mains over- or under-voltage conditions (±10%), or excessive phase-angle output-stage power dissipation. If any of the these fault conditions is sensed while the amplifier is in Standby or full on, the amplifier turns full off. In addition, the 331 employs a new DC servo to protect the loudspeakers against voltage offsets. It can compensate for up to 1V of DC at the amplifier’s input. If the DC is larger than that, the amplifier will shut down. The muting relays operate in the shunt mode, with no signal contacts in the direct signal path.

The No.331 is built from the best assets of the No.20-series circuitry, coupled with design innovations from the No.33 Reference amplifier, and further refined through listening tests. In designing the 331, the full design team participated in listening tests of all the circuit features—a process they refer to as “comping”—including optimizing the use of passive components (resistors, capacitors, etc.). There is no point, for example, in using, say, a $5 Vishay resistor in a place where it has no effect on the amplifier’s sound.

All mechanical bolts and fittings are brass, so that electrochemical reactions between different metal types do not occur to cause corrosion and aging of the mechanical connections, which can give a increasingly harsh quality to an amplifier’s sound over time. For example, a brass screw holds the copper bus bar to the electrolytic capacitors, and is threaded into a brass fitting.

The ‘331’s build quality is superb, better than I’ve seen in almost all other audio products. If weight, shielding, and size of heatsinks mean anything, then the No.331 should run much longer and more reliably than the No.27, which already has seen five years of steady, unbroken service in my listening room.

Sound: neutrality & transparency

Driving the Quad ESL-63s, the No.331 had stiff competition—my well-broken-in No.27 from the same manufacturer. I’d grown accustomed to this amplifier’s treble detailing, which brought out the upper range of my Quad ESL-63s. With the No.27 connected to the Quad ’63s and the KSA-250 driving the Bag End subwoofers, the overall effect was a natural, sweet, somewhat shallow, but detailed soundstage.

Within a minute after hooking up the new Levinson amplifier to the Quads, any doubts I may have had about how the ‘331 would fare were put to rest. These initial impressions did not change after hours of listening. The No.331 added new ingredients: greater transparency, greater depth of soundstage, and total neutrality. This made it hard to describe, because the amplifier’s sonics were not silvery like the No.27’s, nor dark like those of the original Levinson ML-2 or the first No.20s I auditioned in my listening room. Nor did it have the warm midrange of the No.27.5. Determining its character would take much more listening.

Driving either the Quads or Snells, the No.331 produced a wide and deep soundstage, easily the equal of the Krell KSA-250 which used to produce the best soundstage depth in my listening room.. This could be clearly heard on the opening of “Hotel California” on the Eagles’ live Hell Freezes Over album (Geffen GEFD-24725). The placement in space of the audience sounds, the acoustic guitars, and the conga drums were all well-defined, giving the impression of a very wide, deep soundstage. The openness and naturalness of the lead vocalist’s voice and the great dynamic reserves of the ‘331, all served to sweep me into the music. Again and again I found myself becoming involved in music that sounded three-dimensional, vibrant, and clear.

I was able to hear a distinct layering of the harp, clarinet, organ, and male and female choirs on Rutter’s “The Lord is My Light and My Salvation,” the second cut on Reference Recordings’ Requiem. The No.331’s ability to produce a well-defined soundstage was evident on the LP from the original soundtrack of the motion picture Glory (Virgin 90531-1). The choir spread from wall to wall in the opening cut, “A Call to Arms.”

With the No.331 driving the Snell Reference Towers, the midrange was balanced, neutral, and grainless, with none of the forwardness JA had described in his review of the Levinson No.23.5 (Vol.14 No.9). The new Mark Levinson was as smooth in rendering orchestral textures as my well-broken-in No.27. Like the 27, the No.331 delivered a richness of orchestral timbre, especially on woodwinds, that was missing from the Krell KSA-250’s presentation.

The No.27 rendered a silvery, sweet quality to cymbals and hi-hats at the finish of Richard Thompson’s “Why Must I Plead” (Rumor and Sigh, Capitol CDP 95713 2). The new No.331 played the same selection with more transparency and neutrality. It added clarity and realism to pop vocals, allowing me to hear more of the timbre and harmonics in David Bowie’s voice on the Cat People soundtrack (MCA 1498), and Willie Nelson’s voice singing “Getting Over You” on his Across the Borderline (Columbia CK 52752) than I had heard before. I particularly enjoyed comparing changes in Don Henley’s voice, which was lighter and clearer on the original Hotel California LP (Asylum 7E-1084) than heard on the live CD performance recorded 14 years later, where his voice is rougher, more resonant, and narrower in range.

The No.331 was run in gain-matched comparisons with the Mark Levinson No.27 and Krell KSA-250 amplifiers. The treble response of the Levinson ‘331 was free of the colorations heard with the other amplifiers. Compared to the KSA-250 and the No.27, the 331 delivered a more neutral, distant-but-layered version of orchestral textures, and recreated the sense of the hall heard during the brass finale of Janácek’s Sinfonietta: Finale (Reference RR-65CD, José Serebrier, Czech State Philharmonic). There was no glare or harshness to the trumpets during the peaks, and no congestion or hardness during these orchestral climaxes. Listening to Bruce Yeh’s Ebony Concerto (Reference RR-55CD) with the No.331, I was more aware of small treble-range details, such as snares in the drum heads, just behind the clarinet.

The No.331’s high-end treble openness remained intact at higher volumes and in my larger listening room, when driving either the Quad panels or the Snell Reference Towers. The acoustic space around the instruments was clearly heard after climaxes, when the sound of cymbals and bells died away during the HDCD-encoded band arrangement of the Chorus Line overture on the Beachcomber album.

To examine the new amplifier’s bass response, I used it to drive the massive Snell SUB S-1800 18″ bass-reflex subwoofers. The older No.27 amplifier, because its gain exactly matched the new amplifier, drove the Snell Type A Reference towers. For comparison purposes, the same musical selections were played with the (gain-matched) Krell KSA-250 driving the subwoofers.

The No.331 proved to be a formidable bass amplifier. The No.331 sustained the deep thunder of the HDCD-encoded Lay Family Concert Organ and shook the room while playing the John Rutter Anthem “The Lord is My Light and My Salvation” (Joel Martinson, organist; Reference RR-57CD). Besides bass level, the ‘331 controlled the huge Snell woofer cones well.

These qualities added greatly to the drama in the rewritten opening of the Eagles’ “Hotel California” on Hell Freezes Over. A thunderous kick drum, overlaid with conga drums and then some kind of pitched low-bass instrument playing a tonic-dominant line, announces the first appearance of the song’s melody: these drums erupted with great power with the No.331-driven subwoofers. The No.331 was able to deliver the most stunning impact from the explosive synthesizer opening of Terry Dorsey’s “Ascent” on Time Warp (Erich Kunzel, Cincinnati Pops, Telarc CD-80106) when compared to the No.27, a sign that the new amplifier had generous amounts of bass “slam.” It equaled the Krell KSA-250 in capturing the startling, shot-like plucked notes of Abe Laborial’s bass, and Randy Edelman’s synthesizer during “Something’s Wrong,” from the soundtrack to My Cousin Vinny (Var;gese Sarabande VSD-5364), with more solidity, weight, and authority than heard with the No.27. The No.331 captured the burning pace generated by the tom-tom strokes and subterranean synthesizer chords on David Bowie’s “Putting Out the Fire” cut from Cat People.

The No.331’s quickness was also coupled with definition, as heard during comparison with the No.27. Clearly discernible pitch changes in deep bass notes were heard best from the No.331 re-creating Terry Bozzio’s drums and Tony Hymas’s keyboards on “Behind the Veil” on Jeff Beck’s Guitar Shop (Epic EK 44313). The 331 amplifier had excellent bass-range response on sustained deep notes; this was heard clearly on both the Quad/Bag End and the Snell Reference system. But just as important, the amplifier was incredibly dynamic, bringing out the energy and pace in popular music and jazz when driving two very different loudspeaker systems.

The No.331, working as either a midrange-treble or a bass amplifier, was a real tonic for my two very-different speaker systems. The Quad ESL-63s, in particular, really came alive when driven by the new Levinson amplifier. This amplifier’s excellent dynamic range and ability to clarify orchestral textures in the upper midrange and treble overcame the Quad’s inherent dryness and reticence in this area. The Eagles’ “Hotel California,” plus the band arrangement of the Chorus Line overture on the HDCD-encoded Beachcomber album (Frederick Fennell, Dallas Wind Symphony, Reference RR-62CD) were totally involving on both loudspeaker systems. I found myself playing these two selections over and over. The thrill, the dynamics, and the electricity were there each time.

Conclusions

This review of the Mark Levinson No.331 suggests that a superb 100Wpc stereo amplifier can be developed through careful refinements introduced over three product generations. The original No.27 had a sweet, smooth midrange and treble, but lacked bass slam. The No.27.5 added low-frequency extension and dynamic range, but had a more forward midrange, less woofer control, and a shallower soundstage, I felt. The No.331 retains all the assets of the earlier amplifiers, but with a less aggressive midrange, deeper apparent soundstage, and much better woofer control.

But the advances are more than evolutionary. The Mark Levinson No.331 has a neutral, grainless midrange that allows it to develop the soundstaging and depth that I found lacking in the No.27.5. As a result, the No.331 is the best-sounding Mark Levinson dual-monaural amplifier I’ve heard. Its ability to breathe life into loudspeakers in the form of extended, neutral midrange and highs is very good news for Quad ESL-63 lovers. Never have my Quads sounded better. This mix works well for dynamic loudspeaker systems as well, as shown by the No.331’s ability to function superbly as either a subwoofer amplifier or as a midrange/tweeter amplifier in the full-range, bi-amplified Snell Type A Reference System.

The No.331’s build quality is up to the highest standard found in high-end products today. This amplifier’s sonics, superb parts quality, overkill power supply, reduced price compared with its predecessor, and five-year warranty offer its owner lots of value for the money, and bring a Class A recommendation from me. The Mark Levinson No.331 should be auditioned by anyone in the market for a topflight, solid-state, 100Wpc stereo amplifier.

Description

Description: Solid-state stereo amplifier.

Rated output power, 20Hz–20kHz, with no more than 0.5% THD (FTC):

100Wpc minimum continuous into 8 ohms (20dBW);

200Wpc minimum continuous into 4 ohms (20dBW);

400Wpc continuous into 2 ohms (20dBW).

Peak output voltage at rated line voltage: 48V into 8 ohms.

Frequency response: 20Hz–20kHz ±1dB.

S/N ratio (main output): <–80dB (ref. 1W).

Input impedance: 100k ohms balanced, 50k ohms single-ended.

Voltage gain: 26.8dB. Input sensitivity (for 2.8V output): 130mV.

Input sensitivity (for full output): 1.3V.

Output impedance: !x0.05 ohms, 20Hz–20kHz.

Damping factor: >800, 20Hz–20kHz into 8 ohms.

Power consumption: typically 260W at idle, 110W in standby.

Dimensions: 17.56″ (446mm) W by 18.85″ (479mm) D by 9.3″ (232mm) H; faceplate curve depth 1.22″ (31mm). Shipping weight: 112 lbs.

Price: $4550 (1996); no longer available (2009). Approximate number of dealers: 75.

| Impedance | Both Channels Driven | One Channel Driven | |

| Load | W (dBW) | W (dBW) | W (dBW) |

| ohms | L | R | L |

| 8 | 134.4 (21.3) | 135.3 (21.3) | 134.5 (21.3) |

| Line voltage | 118V | 118V | 118V |

| 4 | 254.3 (21.1) | 254.7 (21.1) | 254.1 (21.1) |

| Line voltage | 117V | 117V | 117V |

| 2 | 453.6 (20.6) | ||

| Line voltage | 117V | ||