Vivid Audio B1 (Upgraded) – Matt Black

Original price was: R375,000.00.R88,000.00Current price is: R88,000.00.

| Specifications | Vivid Audio B1 |

|---|---|

| Configuration | 3 way vented cabinet |

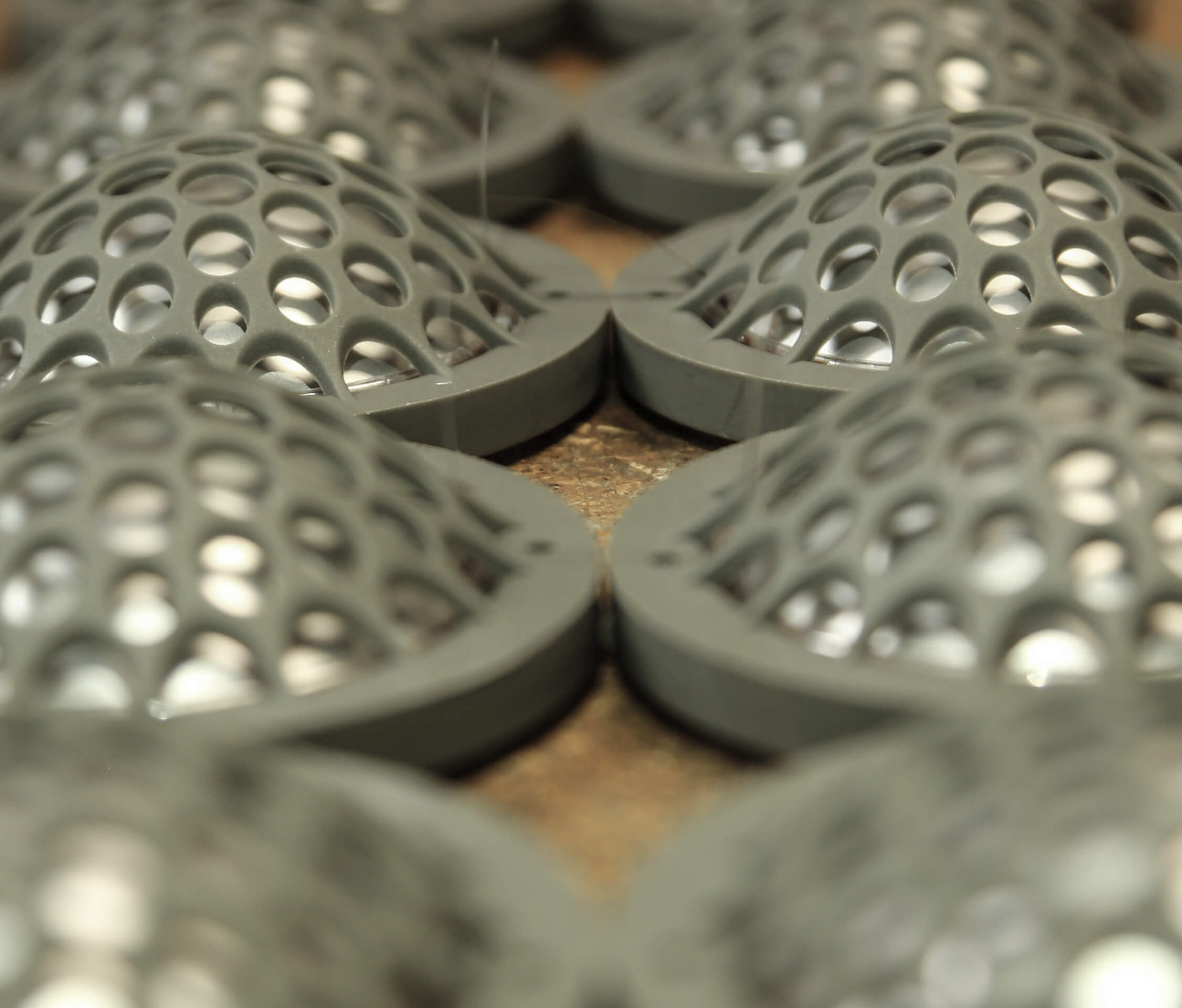

| Cabinet material | Complex loaded carbon fibre filled polymer |

| Drive units | HF: D26 – 26mm metal dome unit with tapered tube loading MF: D50 – 50mm metal dome unit with tapered tube loading LF: C125 – 2 x 125mm metal coned unit (coupled) |

| Sensitivity | 89dB @ 2.83VRMS at 1m on axis |

| Nominal impedance (Ω) | 4 |

| Frequency range (Hz) | 35 – 36,000 Hz (-6dB) |

| Frequency response (Hz) | 39 – 33,000 Hz +/- 2dB on reference axis |

| First D26 Break Up mode: | 44,000 Hz |

| Harmonic distortion (2nd and 3rd harmonics) |

< 0.5% over frequency range at 1W |

| Cross over frequencies (Hz) | 100, 900, 3,500 |

| Power handling rms | 300W |

| Loudspeaker dimensions | 1,202mm (H) x 370mm (W) x 374mm (D – cabinet), 420 (D – base) |

| Net weight | 38kg |

| Shipping dimensions | 1,250mm (H) x 430mm (W) x 530mm (D) |

| Shipping weight | 50kg (each) |

Description

Vivid Audio B1 loudspeaker

When John Marks wrote about the Vivid B1 in his column, “The Fifth Element,” in February 2011, he was so excited about the sound he was getting that he asked me to drive up to Rhode Island to give a listen for myself. Not only was I impressed by what I heard at John’s, I decided to do a full review of the speaker.I first heard the B1 ($14,990/pair), Vivid’s first product, when it was demmed at the 2004 London Heathrow show, but it didn’t reach the US until the 2006 Consumer Electronics Show. The B1 is made in South Africa and engineered by ex-B&W designer Laurence “Dic” Dickie, who was responsible for B&W’s original Nautilus loudspeaker.

I admit that I was put off by the Vivid B1’s appearance. Some have compared it to a Zulu shield, others to a creation by H.R. “Alien” Giger. Perhaps it says something about my psyche that I found it reminiscent of something a little more, er, intimate. But after Vivid raised the weird-speaker stakes with the Smurf-styled G1 Giya, which Wes Phillips enthusiastically reviewed for Stereophile in July 2010, I started to like the look of the B1. And like the G1 Giya, its appearance is a case of form following function.

Drive-units get smaller as the range they handle rises in frequency, due to the fact that the wavelengths of those sounds also become smaller. Similarly, the optimal size of the baffle on which that drive-unit is mounted also decreases with increasing frequency. So while a nice wide baffle is ideal for mounting woofers, it is suboptimal for the midrange unit, and even less optimal for a tweeter. The B1’s baffle therefore decreases in size as the drive-unit ranges increase in frequency, and this profile is echoed below the woofer to produce a vertically symmetrical shape. While it looks like a stand-mounted speaker, the B1’s stand and base are integral parts of the enclosure. The enclosure material is polyester loaded with carbon fiber.

The B1 uses a 6.25″ aluminum-cone woofer operating below 900Hz and loaded by a flared port below it on the baffle, a 2″ aluminum-dome midrange unit to cover the range from 900Hz to 4kHz, and a 1″ aluminum-dome tweeter. Though it therefore appears to be a three-way design, there is a second 6.25″ woofer on the B1’s rear panel, along with a second port. (The front and rear ports are in-line—you can see right through the speaker.) The rear woofer increases the B1’s dynamic range capability in the low end, but is rolled off above 100Hz, to minimize interference between the spaced drive-units in the midrange. The opposed woofers are driven in phase, and their chassis are connected to each other with a screw-tensioning bar so that any vibrational excitation of the enclosure is canceled. The tweeter and midrange unit are mounted on rubber O-rings, again to isolate them from the enclosure.

The drive-units used in the B1 were all developed by Vivid and are manufactured in-house. In their design, Laurence Dickie paid particular attention to the sound emitted from the rear of the diaphragms. The tweeter and midrange domes use radially polarized rare-earth ring magnets that present very little acoustic obstruction behind the dome. The dome’s backwave fires into a large-diameter tapered hole in the pole piece, this attached to a fiber-damped, exponentially tapered tube—in effect, an inverted horn—that runs the speaker’s entire depth. As in a transmission line, the backwave from the tweeter and midrange domes is absorbed without reradiating back through the diaphragms. The woofer also uses a radially polarized rare-earth magnet assembly, this time with a diameter not much greater than that of the voice-coil, and the 12 struts connecting the cast frame to the magnet assembly are profiled to present the smallest possible surface area to the backwave.

The crossover filters are fourth-order and are connected to the two pairs of WBT binding posts in the base via wires that run through the struts of the integral stand. The base is fitted around its periphery with five removable spikes that can be adjusted for maximum vibrational coupling to the floor. There is no grille; the domes are protected by a skeletal crosspiece.

Once you get used to its idiosyncratic looks, the B1 is a stunningly beautifully finished speaker that incorporates engineering of equally stunning beauty.

Listening

My review samples of the B1 were the ones I had heard at JM’s, finished in a smart Graphite (dark gray) gloss metallic paint. This much-traveled pair had been used at the 2010 SSI Show in Montreal, and had visited another reviewer on their way to JM—and by the time they arrived here, the 50mm midrange dome of one speaker had been destroyed in shipping. Vivid shipped me a replacement assembly of dome, voice-coil, and magnet, with which I replaced the damaged one. The entire assembly screws into the tapered transmission-line tube, which is then securely fastened to the enclosure’s rear with a crosshead bolt. I took before-and-after measurements of the damaged speaker, as well of its undamaged sibling, so that I could be sure that my repair job hadn’t compromised the B1’s sound. After the repair, the two samples matched extremely closely: within 0.5dB throughout the region covered by the replaced unit.

Setting up the speakers was more difficult than usual, in terms of getting smooth integration of the mid- and upper-bass regions and the midrange. At first I was getting rather “puddingy” low frequencies that sounded a little isolated from the speakers’ upper ranges. Moving each speaker half an inch at a time, from side to side or forward and backward, I ended up with a balance that sounded smoothly blended from the midbass up. Each speaker’s front woofer, which is 32″ from the ground, ended up 80″ from the wall behind it and 48″ from the nearest sidewall, though the first 15″ of that wall comprises record cabinets and bookcases. I toed in the speakers to my listening seat and, once I’d optimized those positions, fitted each base with the five carpet-piercing spikes.

The Vivid’s low-frequency character was vulnerable to cable changes, added to which was the fact that the two pairs of speaker terminals are under a lip at the rear of the base, which complicates the use of stiff cables fitted with spade lugs: There just wasn’t enough clearance for the AudioQuest Wild cables that I’d been using up to the B1s’ arrival. I tried Audience’s Au24 e cables, which Brian Damkroger highly recommends, and which have 4mm connections rather than spades and are thin enough to be easily dressed. However, even with the Classé CT-M600 monoblocks, which have superb bass control, these sounded too warm. I ended up using a single pair of Cardas Neutral Reference speaker cables, which John Marks recommended a few issues back. These have terminating pigtails flexible enough to fit into the limited space that was available, and I connected the two pairs of terminals with the shorting straps provided by Vivid.

It seems odd to use the word “generous” to describe the B1’s low frequencies, given its fairly small footprint and small-diameter woofers. But generous those lows were indeed. The bass guitar on the “Channel Identification” and “Channel Phasing” tracks on my Editor’s Choice CD (Stereophile STPH016-2) had excellent weight, and the speakers had superb articulation with this signal, which can often sound soggy with reflex designs. Jerome Harris’s solo bass-guitar introduction to Duke Ellington’s “The Mooche,” from the Jerome Harris Quintet’s Rendezvous (CD, Stereophile STPH013-2), sounded even, with, again, superb articulation.

The B1 dealt similarly well with classical organ recordings; the pedal lines in Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in D, performed by Michael Murray on the organs at Los Angeles’s First Congregational Church (CD, Telarc CD-80088), had surprising weight and depth without sounding boomy. The low-frequency warble tones on Editor’s Choice were reproduced in full measure down to the 32Hz 1/3-octave band. Though there was still some output at 25Hz, the 20Hz band was silent—not even any port wind noise was audible. The half-step–spaced toneburst track on the same CD spoke cleanly, with no undue emphasis.

At the other end of the spectrum, the B1’s high frequencies were clean, clear, and free from grain, although it’s also fair to say that they were far from reticent. The speaker didn’t sound bright or tipped up, but the B1 was by no means a mellow speaker. The Vivid’s treble balance was not a problem with naturally balanced recordings, like the St. Louis Symphony under Leonard Slatkin performing Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis (SACD, Telarc SACD-60641). But it was a little too revealing of the rather “shouty” orchestral balance in the 1970 recording of Oistrakh, Rostropovich, and Richter performing the Beethoven Triple Concerto with von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic (CD, EMI Great Recordings of the Century 5 6655954 2). This treble balance also made the B1 more suitable for use with sweet-toned amplifiers, like the Musical Fidelity AMS100 I reviewed last month, rather than the MBL Reference 9007 monoblocks, which adhere more to the cleaner-but-leaner school of sound. But with well-matched amplification, even recordings that I was not expecting much from—such as Phish performing an empathetic live version of Little Feat’s “Time Loves a Hero” that I’d downloaded as a FLAC file, following a recommendation from a Facebook friend—had impressive presence without sounding too, er, vivid.

Dynamics were impressive for a relatively small speaker. With the Classé CTM-600s providing the muscle, the explosive beginning of “Speed,” from Dean Peer’s Airborne (24/96 AIFF file, Cardas), was suitably explosive. The drum samples on Cornelius’s “Fit Song,” from Sensuous (CD, Warner Japan EVE016), had superb “jump factor.”

John Marks enthused about the coherence of the B1’s midrange, and I , too, was impressed by its combination of clarity and purity in that region. I heard no colorations; both the sound of Vladimir Ashkenazy’s piano and the space around the instrument, in his 1970 performance of Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini with André Previn and the LSO (CD, Decca Jubilee 417 702-2), were naturally presented. Decca’s engineering team was at the top of their game with this Kingsway Hall recording, though the B1’s clarity and generous lows allowed me too easily to hear the subway train pulling away from the station at the start of the big, inverted tune in the famous slow variation.

The complex layering of the vocal parts in “Dawn,” from Meredith Monk’s Book of Days (CD, ECM 1399), which Jon Iverson recommended to me, was laid bare but without any sense that the speaker was, in the infamous phrase, “ruthlessly revealing.” The B1 was simply stepping out the way of the information on the recording. It also produced a palpably real feeling with voices. Peter Gabriel’s tortured baritone in Paul Simon’s “Boy in the Bubble,” from Gabriel’s Scratch My Back (ALAC file ripped from CD, Real World 1), had a sense of presence I have rarely heard from a speaker. I remember Meridian’s Bob Stuart conjecturing, decades ago, that there was something special about the reproduction of human voices by a loudspeaker whose baffle was about as wide as a human head. The head-width B1 certainly worked some special magic with the sound of voices.

And the B1’s way with imaging in general was simply superb. The combination of imaging stability and precision, coupled with the B1’s high resolution, allowed me to hear miking anomalies, such as the way the violin and cello sections each clumped into a single location in the 1974 performances by Stephen Kovacevich, with the BBC SO under Sir Colin Davis, of Beethoven’s Piano Concertos 2 and 4 (SACD, Pentatone PTC5186 101). And the too-close miking of the solo instruments in the recording of Beethoven’s Triple Concerto mentioned earlier was made clear enough that it got in the way of my enjoyment of the performance.

At the New York AXPONA Show in June, when I was preparing this review, I was fortunate to have heard Arturo Delmoni give a dazzling performance of the Chaconne from Bach’s Partita 2 in d for solo violin. So when I got home from the show, I cued up his recording of the same work (ALAC file ripped from gold CD, John Marks JMR 14). Captured by Kavi Alexander with a pair of EAR/Milab microphones, the image of Delmoni’s violin hung between the Vivid B1s, uncolored, solid, and stable. No, it wasn’t live, but the sympathetic acoustics of the Santa Barbara chapel, lit up by the violin and occupying the width and depth of the soundstage, were infinitely preferable to Delmoni performing the Chaconne in a dry hotel suite at AXPONA. It doesn’t get any better than this synergy between performance, recording, and playback system.

Summing Up

In his column, John Marks summed up the Vivid B1 as having a “near-perfect balance of warmth and information.” After all the work that has gone into this review, I don’t actually have much to add to that statement. At close to its price of $14,990/pair, the Vivid B1 comes under pressure from: the Wilson Audio Sophia Series 3 ($17,600/pair), which Art Dudley reviewed in February 2011; the Thiel CS3.7 ($13,900/pair), reviewed by Wes Phillips in December 2008; and the Revel Ultima Studio2 ($15,999/pair), which Kalman Rubinson reviewed in March 2008. For not too much more, there are the KEF Reference 207/2 ($20,000/pair), which I reviewed in February 2008; and the Revel Ultima Salon2 ($21,999/pair), reviewed by Larry Greenhill in June 2008. These are all first-class loudspeakers, with any of which I could live happily ever after.

But if your room is of small to medium size, and you want a less obtrusive speaker (though its idiosyncratic looks do come into the equation), and you value clarity and overall musical communication over gut-busting dynamics, the Vivid B1 is one of the best choices around. I loved what it did!

Note: Measurements taken in the anechoic chamber at Canada’s National Research Council can be found through this link.

Fool’s gold (iron pyrites) is a common mineral that some might mistake for the real thing. Pity the sucker who pays a premium price for something worthless. No doubt that’s often happened in the mineral biz, but it also happens again and again in the ultra-high-price loudspeaker market. Contrary to what many big-spending audiophiles might want to believe and other writers might want you to think, in loudspeakers, there is no correlation with price and performance. In my 15 years of reviewing I’ve come across way too many speakers priced over $10,000 that use subpar technology to deliver sound that’s inferior to that of speakers costing only a fraction of the price. Too much of the time it’s a lot of hype with very little substance, and the consumer is ripped off.

Fool’s gold (iron pyrites) is a common mineral that some might mistake for the real thing. Pity the sucker who pays a premium price for something worthless. No doubt that’s often happened in the mineral biz, but it also happens again and again in the ultra-high-price loudspeaker market. Contrary to what many big-spending audiophiles might want to believe and other writers might want you to think, in loudspeakers, there is no correlation with price and performance. In my 15 years of reviewing I’ve come across way too many speakers priced over $10,000 that use subpar technology to deliver sound that’s inferior to that of speakers costing only a fraction of the price. Too much of the time it’s a lot of hype with very little substance, and the consumer is ripped off.

Because of this, I eye every new speaker on the market with suspicion, and it’s why for so long I basically ignored Vivid Audio. The B1, Vivid’s first product and the subject of this review, was released some six years ago, and retails today for $15,000 USD per pair. Since then, Vivid’s product line has grown to six models of main speakers; the B1 is now fourth down from the very top model, the radical-looking G1 Giya. But when I first saw the B1, I only glanced at its exterior and thought it another case of style over substance. And because I never had a good chance to listen to it back then, and very few people talked about the sound, I figured it couldn’t be all that great.

That changed this year, when I had a chance to examine the speaker closely and listen to it at length. It was then that I knew that its appearance was deceiving — there’s a lot more to this speaker than meets the eye. Its sound is quite something, too. Too little too late? Let’s hope not, and that I can finally set the record straight.

Description

Vivid Audio is a multinational entity. The speakers are manufactured in South Africa but designed in England by Laurence Dickie, who was previously with B&W, and was responsible for the design of the original Matrix-series cabinets, as well as B&W’s legendary Nautilus loudspeaker. I used to own a pair of Matrix 1s, but never knew I had Dickie to thank for them. Elements of his earlier work are visible in his Vivid designs, but there are also many unique things that appear to be new.

Most obvious is the B1’s 48″H, 21″D cabinet, which has a teardrop shape and an integrated stand that can’t be removed. I like the elegant, distinctive look — it’s quite unlike anything else out there — but not everyone else does. Many feel the B1 looks too bizarre for a speaker, a comment that goes double for the G1 Giya.

The cabinet, made of polymer concrete, is extremely strong and exceptionally “dead,” in an obvious attempt to eliminate cabinet-induced vibrations. It’s also heavy — about 85 pounds. Six standard finishes are available: Arctic, Sahara, Oyster, Borollo, Pearl, and Piano. The finish work is extremely good. Two sets of binding posts, for biwiring or biamping, are affixed to the rear of the base, and are lined up horizontally to keep the bottom plate shallow. These are covered with a “lip” that extends over the connectors to maintain a clean appearance. Stabilizing spikes screw in underneath.

The cabinet, made of polymer concrete, is extremely strong and exceptionally “dead,” in an obvious attempt to eliminate cabinet-induced vibrations. It’s also heavy — about 85 pounds. Six standard finishes are available: Arctic, Sahara, Oyster, Borollo, Pearl, and Piano. The finish work is extremely good. Two sets of binding posts, for biwiring or biamping, are affixed to the rear of the base, and are lined up horizontally to keep the bottom plate shallow. These are covered with a “lip” that extends over the connectors to maintain a clean appearance. Stabilizing spikes screw in underneath.

The B1 is a three-and-a-half-way design claimed to have a sensitivity of 89dB/2.83V/m, an impedance of 4 ohms, and a frequency response of 35Hz-36kHz, -6dB. The drivers are made by Vivid, which I think is important — no one else uses them, which makes the speaker unique. There’s not necessarily anything wrong with using third-party drivers — there are some good ones out there, and if manufacturers don’t have the skill or resources to make their own, they’re the only option. However, successfully making your own drivers requires a certain level of engineering expertise and manufacturing skill that few in the ultra-high-end speaker business have. If you do have those skills and resources, you have the advantage of creating exactly the drivers you need for a particular design.

The B1’s tweeter is a 1″ dome of aluminum with a hint of magnesium, and operates from about 3.5kHz up. The 2″ midrange driver also has a dome of aluminum alloy and works from about 3.5kHz down to 900Hz. Both of these drivers have many important design features that I could go on and on about, but that’s what white papers and technical briefs are for. Three, however, are key:

First, a tapered tube affixed to the backside of each driver terminates at the rear of the cabinet, where it’s securely attached. This dissipates rear-firing energy from the driver, for the smoothest response. Second, the drivers’ domes aren’t perfectly round, but are more parabolic, to spread out the breakup modes and push the nastiest resonances to frequencies high above the audioband. A typical pure-aluminum-dome tweeter would generally “ring” somewhere around 20kHz, which is very close to the top of the range of human hearing. According to Vivid, the B1’s midrange won’t ring until 20kHz, and the tweeter not until 44kHz. Each of these frequencies is far away from the areas in which these drivers operate, which means that each driver operates “pistonically” within its assigned range. Third, the drivers are suspended on the front baffle with O-rings, to reduce the transfer of energy from them to the already-dead cabinet.

The front and rear woofers have 6.5″ aluminum-alloy cones and are also suspended with O-rings. The rear-firing woofer is said to operate up to about 100Hz before it’s rolled off with a shallow slope. The front-firing woofer goes up to 900Hz, where it hands off to the midrange driver. These different crossover points and overlapping ranges are what make this a “three-and-a-half-way” design. If both woofers ran up to 900Hz, it would be a simple three-way design with two woofers run in parallel. Laurence Dickie didn’t do this because of the problems that would be caused by the distance between the rear woofer and the midrange. Basically, the distance between drivers should be no more than the wavelength of the crossover frequency. The higher the frequency, the shorter the wavelength, and the closer together the drivers must be placed. The front woofer and midrange are close together, so a 900Hz crossover is fine. Because the midrange and rear woofer are much farther apart, the crossover frequency at which they hand off must be much lower — which is why Dickie chose 100Hz.

Dickie mounted one driver on the front and the other on the rear to create a “reaction-canceling” effect to reduce cabinet resonances, a technique now commonly used in subwoofers. Likewise, Vivid says that the egg-shaped ports are opposed in order to “cancel out any reaction forces they create.”

However, we discovered a problem with opposed woofers through measuring speakers in the anechoic chamber at Canada’s National Research Council (NRC). If you look at our measurements, you can’t miss the huge dip that occurs at around 300Hz in the on-axis frequency response. If you measure the speaker from directly behind, you see the exact same thing. This is due to the identical frequencies reproduced by the rear and front woofers “wrapping around” the cabinet to cause cancellations directly in front of and behind the speaker. Does that mean listeners won’t hear 300Hz and the frequencies that surround it as they should? Not necessarily. When we saw this peculiarity, we took another measurement in the middle of the side of the cabinet, and found that at that position the drivers summed quite nicely, making for a fairly flat response to the sides.

What is the result of all this? Good question, but not one easy to answer. If we listened in an anechoic chamber, then there would definitely be a problem: there would be too little energy at and around 300Hz, because all we would hear would be the on-axis response. But we listen in rooms, where wall, floor, and ceiling boundaries cause reflections. What we hear at the listening position is a combination of the on-axis response (in front of the speaker) and the off-axis response (everywhere else). In a real room, the energy at the sides of the speakers will end up at the listening position by being reflected off the room boundaries. However, that will mean that the bass response the listener hears will have a lot to do with the layout of the room and how and where the speakers are set up in it. As you’ll read below, that made my setup a bit tricky.

Sound

The equipment combo I used with the Vivid B1s sounded absolutely amazing, but I suspect that these speakers will mate well with a number of associated products: the sound had some extraordinary characteristics that were attributable not to the equipment I used them with but to the speakers themselves. I’ve never heard a speaker sound quite as these did using these same pieces of gear. Plus, despite its 4-ohm impedance, the B1 seemed quite easy to drive.

The equipment combo I used with the Vivid B1s sounded absolutely amazing, but I suspect that these speakers will mate well with a number of associated products: the sound had some extraordinary characteristics that were attributable not to the equipment I used them with but to the speakers themselves. I’ve never heard a speaker sound quite as these did using these same pieces of gear. Plus, despite its 4-ohm impedance, the B1 seemed quite easy to drive.

The first thing I noticed was the lack of any sort of cabinet coloration. In all the years I’ve been reviewing speakers, that’s not been the first thing to catch my attention. But with the B1s, the effect was uncanny. When I sat dead-center in the sweet spot, it was obvious that the sound was radiating directly from the drivers, with no resonances from the enclosure. This is in direct contrast to a speaker like the Harbeth Monitor 30, which I reviewed almost two years ago; it sounded very good, but it was obvious with any kind of music I played that not only were the drivers making sound, but so were the boxes. There was a blurred, resonant quality that was completely absent with the B1s. In fact, so noticeable was the lack of any cabinet “sound” — more so than with any other speaker I’ve heard — that I put my hands on the B1s again and again, with all kinds of music playing. The only place I could feel any hint of energy was right at the tip, and even then, it was minuscule. Try that with a typical box speaker.

I think the B1’s extremely dead cabinet was at least partially responsible for the extraordinary resolution and refinement the speaker exhibited in the midrange and highs. I say partially because there were other factors, such as the crossover design and the Vivid-made drivers. It’s hard to know how much each element contributed, but the result was midrange and high-frequency performance that was exceptionally neutral, thoroughly refined, and so wildly transparent and lightning-fast that I recalibrated my internal reviewing scale for how detailed a loudspeaker could be without ever fatiguing me. The B1s were resolving through the mids and highs to the nth degree. What’s more, they maintained these qualities of detail and speed at extremely low levels, and when I played them very, very loud.

Bruce Springsteen’s Tunnel of Love (CD, Columbia 42000) is an interesting recording that I often listen to for the music, but also to hear what it sounds like through different systems. It’s a pure-digital recording from 1987, and it has some strong points — great dynamics for a Springsteen recording, for example, and his voice is well captured — as well as many flaws. The recording’s brashness and hardness in the midrange and top end were still audible through the B1s, but they weren’t exacerbated — a good thing indeed. If a speaker itself has a hard or coarse sound, recordings flawed in those ways, such as this one, can become unlistenable. What I was most impressed with was how neutral the B1s sounded in the mids and highs, and how much more I could hear — mostly, better separation between the musicians, and subtle nuances and spatial cues I hadn’t noticed before.

For instance, toward the end of “One Step Up,” a woman can be heard singing “and I’m pretending” along with Springsteen, but she’s far back in the mix. With most systems she’s hard to pick out, let alone place accurately on the soundstage. Through the B1s her voice was a snap to hear, her placement precise, with clean separation from the other musicians; I could even detect a touch of “air” around her, something I hadn’t heard before.

Likewise, I was floored by the separation of the choral voices in Ennio Morricone’s score for the film The Mission (CD, Virgin CDV2402), a recording I’ve used to test systems with for over 20 years. Lesser speakers will mash the voices into a large wall of sound, no matter what associated electronics you have. The best speakers, driven by high-quality electronics, let you hear individual voices so distinctly that you feel you’ve finally discovered the recording’s very lowest levels of detail. I heard the voices more distinctly through the B1 than through any other speaker I’ve reviewed.

The resolution the B1 was capable of was astonishing, and fully worthy of use with the highest-resolving front-end components you can find. I suspect that most audiophiles would come away from a session with the B1s shocked at how much they can hear through them. I sure was. But the B1 wasn’t all hyped-up detail and nothing else — its neutrality and refinement through the midrange and highs were second to none, including the Revel Ultima Salon2, which I use as a reference and which costs $22,000/pair. People know I like the Revels a lot, but if they now ask me which speakers they should consider purchasing, I say both. They’re peers through the midrange and highs, though the B1 probably has the edge in resolution — I’d never heard so much detail through any loudspeaker before.

However, there were significant differences in the bass. Despite its multi-thousand-dollar price and its unique advanced technology, the B1 is still a modest-size floorstander. I didn’t expect superdeep bass from a pair of 6.5″ woofers in a midsize cabinet, and I didn’t get it — 40Hz or so is about as low as the B1s went in my room. This is not a full-range speaker like the Revel Salon2, which extends solidly down to 20Hz. However, the B1 doesn’t cost nearly as much and isn’t nearly as large. It must also be said that Vivid offers three larger, more expensive speakers that better plumb the depths.

The B1’s bass isn’t about depth but “punch.” When playing kick-drum-heavy music through the B1s (e.g., most rock recordings), I noticed a greater-than-average wallop that made it seem as if I were listening to much larger speakers. This bit of boost was consistent regardless of the music I was listening to, and it was pretty obvious to me what was happening: There was quite a lot of energy in the upper bass, something that’s often designed into small- or medium-size speakers to give a more convincing impression of bass “weight.”

Sure enough, our measurements reflected just that: an emphasis at 100Hz at least 3dB over what would be seen in, say, the Salon2, which has “weight” simply because it can reach down to 20Hz. This emphasis in the B1 was also why it sounded quite different from the Magico V2 ($18,000/pair), which I reviewed over a year ago. The V2 goes impressively deep in the low end — lower than the B1 — but it lacks energy in the 80-100Hz region. In fact, long after I’d written that review, while listening to some other speakers, I realized why I kept throwing more and more power at the V2s: not to make them play louder, but to make them come more alive in the bass.

In contrast, despite its lack of really low bass, the B1 packed a wallop, and didn’t need all that much power to come alive. Playing through the B1s a percussion-heavy track like “Objection (Tango),” from Shakira’s Laundry Service (CD, Epic 498720), I got the sense that they could really boogie. In contrast, the Magico V2s sound slow. All in all, I liked the B1’s voicing in the bass despite its departure from ruthless neutrality in the mids and highs. Such a sound suited this speaker well. After all, the last thing you want in a moderate-size speaker is that it sound thin or light — and the B1 didn’t.

However, this emphasis at 100Hz, coupled with the cancellation effect at 300Hz, meant I had to finagle the B1s’ placements in my room more than I normally do. This was a bit of a surprise at first, because we measured them after I’d done all the hard setup work and most of my listening. Had I known at the beginning what I knew post-NRC, things would have been different; when I began listening, I was a little perplexed as to why it was so tricky to get the B1s to sound just right in the low and upper bass.

In a nutshell, with the speakers pulled way too far away from the walls, I lost some of the low-frequency reinforcement the walls provided. This meant less deep bass, but I also felt the upper bass was too recessed — which, I guess, had something to do with the cancellation effect coming into play. The farther a speaker is from the walls, the less it interacts with them, so I wasn’t getting enough energy at and around 300Hz. In the end, I found that I had to place the B1s a little closer than I usually do to the front and side walls, to take more advantage of those boundaries in getting more linear upper-bass response and deeper low-bass response — but at the same time, I had to ensure that I didn’t excite too much that 100Hz hump.

When the B1s were finally set up correctly, I’d attained respectable low bass (to about 40Hz), and a properly balanced upper bass that blended exceedingly well with the mids and highs. One of my tests for seeing if I’ve attained a good overall response is a great piano recording, such as Ola Gjeilo’s Stone Rose (SACD/CD, 2L 2L48SACD). From the lows to the highs, the tonal balance was right, with no frequency dominating any others. This recording also taught me that the B1s’ reproduction of the sound of the acoustic piano was spot-on and tremendously precise. In fact, set up properly, there was hardly anything the B1s couldn’t do right, with any type of music.

The B1’s tricky setup isn’t a deal breaker, but it was time-consuming. However, once that was done, I was enthralled by the speaker’s overall performance, and in particular with its extraordinary resolution in the mids and highs. Playing Bruce Cockburn’s Humans: Deluxe Edition (CD, True North TND 317), a recording I first purchased on LP 30 years ago, and hearing things through the B1s that I’d never heard before, it was obvious to me that hi-fi equipment for the home has advanced significantly in those three decades. Based on what I heard from the B1, Vivid Audio, despite being a relatively new brand, is a company whose products can be considered at the top of the heap.

Conclusion

Vivid Audio’s B1 is an extraordinarily good loudspeaker that has midrange and high-frequency neutrality, transparency, and refinement that are second to none. In resolution and detail in those mid- and upper ranges, every other speaker I’ve heard comes in second to it. Listening with the B1 was like training a microscope on my records — it was truly revelatory in that regard. This makes the B1 a reference-caliber monitoring tool and a great home loudspeaker.

But the B1 isn’t perfect — just close to it. Its mids and highs bowled me over, but not its bass. I wish its low bass went slightly deeper, and mostly that setting them up to get the smoothest, deepest low- and upper-bass performance wasn’t as tricky as it turned out to be. Those are my biggest beefs. However, those drawbacks will be somewhat room-dependent, and there are three Vivid models above the B1 that are all larger. Usually, bass performance gets better as the speaker gets bigger.

The B1 isn’t the only thing that impressed me about Vivid — the company itself has. For a relatively new speaker company to make all the major parts used in its products is as extraordinary as the B1 itself. Vivid Audio is no bunch of “kit builders,” but true loudspeaker makers who are creating something distinctive from the ground up. I also admire Vivid for producing something so visually interesting. Not everyone will like the B1’s looks, but many will — and I think most will agree that its appearance makes the speaker as unique as the parts it uses.

Obviously, these Vivid guys from England and South Africa comprise a bona-fide high-end force, and their B1 is no fool’s gold of a loudspeaker. I think it’s well worth 15 grand — there isn’t a speaker costing less that I like more. The only fool would be the person who spends anywhere near $15,000 on something else without first listening to these. And you can consider me a fool for having overlooked Vivid Audio and the B1 for so long, based on mere assumptions. Now, finally, I hope I’ve set the record straight.

Based on the “findings” on a recent thread (see below), on the differences between the Vivid B1 & B1 Decade, here’s how I would cherry pick that information to highlight the differences. Also noted is a smattering of comparison to the Decades, its second highest sibling from the G-series, the G2. ( Reference is also made to KEF’s Blade II). This is a quick edited overview of all three speakers taken from Doug Sneider’s review(see blow):

“Late to the party but at last intrigued, I reviewed the Oval B1 later that year. When I did, I realized that it had been an oversight on my part not to look at their speakers before — the Oval B1 wasn’t perfect, but its sensational sound made it my favorite speaker for under $20,000 USD per pair. (The retail price was then $15,000/pair; it’s now $18,000/pair.)……

Description

Laurence Dickie told me that the first choices he made in the redesign of the Oval B1 were of what would remain unchanged: its overall shape of an oval main cabinet permanently affixed to a stand and base, the whole looking vaguely like a tennis racket; and its three-and-a-half-way driver configuration of front-firing tweeter, midrange, and woofer, with a second woofer firing to the rear.

Then came the differences. The B1’s entire cabinet, stand, and base are made of a mineral-filled resin composite; in the B1D, that material is used only for the stand and base. The B1D’s cabinet is made of the same materials as the Giya series: vacuum-infused, fiberglass-reinforced resin sandwiching a balsa core. The resulting light, stiff cabinet has a much higher resonant frequency than the B1’s, meaning that any cabinet resonances are even less likely to be heard when the speaker is reproducing music. According to Dickie, the switch to the newer, far more labor-intensive materials accounts for most of the $10,000 difference in price between the B1 and B1D……

The B1D uses Vivid’s D26 1” (26mm) dome tweeter and D50 2” (50mm) dome midrange driver, both of which are used in the B1 and are here crossed over at the same frequency: 3500Hz. But instead of being left unprotected, as in the B1, each driver has its own permanently affixed grille…….

….The B1D’s two C125 woofers have 5” (125mm) aluminum-alloy cones and include improvements over the woofers used in the B1. (Including the surround, the driver is actually about 6.5” across.) The main difference is that Dickie has moved the magnet from the rear so that the magnet now surrounds the coil…….

..As in the B1, the B1D’s rear woofer operates with full force below 100Hz to supplement the front woofer in the lowest frequencies, but is rolled off above that frequency. The front woofer operates throughout the bass range until it hands off to the midrange at 880Hz. The B1D’s bass extension is specified as 35Hz…

The B1D’s new woofers, and the redesign of the crossover to accommodate them, produced profoundly different results when we had the speaker measured in the anechoic chamber at Canada’s National Research Council. In the charts plotted for the measurements of the original B1, a large cancellation of about 8dB was visible just below 400Hz when the microphone was placed directly in front of the speaker, on the tweeter axis — the result of the outputs of the front and rear woofers summing out of phase. But that cancellation didn’t carry the entire way around the speaker. When the mike was pointed at the middle of either side of the speaker, from the same distance away as when measured on axis to the tweeter, the woofers’ cancellation was almost completely eliminated…

…Our measurements show that his work was worthwhile; the cancellation on axis is now only about 2dB — a reduction of 6dB, which is significant…

Sound

….I don’t remember exactly how widely and deeply the B1s presented the soundstages of the recordings I’ve long used as references for that quality, which include Ennio Morricone’s score for the film The Mission (16/44.1 FLAC, Virgin) and the Cowboy Junkies’ The Trinity Session (16/44.1 FLAC, RCA). But I do remember that I was impressed enough that I wrote this about The Mission: “I heard the voices more distinctly through the B1 than through any other speaker I’ve reviewed.” Suffice it to say that all that clarity was still there with the B1Ds, along with a soundstage with the best combination of width, depth, and precise focus of aural images of instruments and voices on that soundstage that I have experienced….

….

The B1’s reproduction of bass is the Achilles’ heel of that otherwise excellent speaker. I found the B1’s upper bass a little too boosted, and the entire lower-to-upper-bass region not quite as tight, detailed, and clear as the frequencies above. That lack of tightness, detail, and clarity created a noticeable lack of integration between the outputs of the front woofer and midrange, and a slight lack of coherence across the audioband — the quality of output of all the B1’s drivers wasn’t quite identical. If I’d had to assign letter grades, I’d have given the B1’s tweeter and midrange an A, the woofers a B. Those woofers needed to catch up.

They have. As mentioned above, the shape of the ports, the crossover, and the woofers themselves are all different in the Oval B1 Decade. The results: no boost in the upper bass, a little more extension in the lower bass, far more detail from the lowest bass through lower midrange, and an ideal blend of the outputs of all four drivers, from lowest lows to highest highs…..

….the transition from midrange driver to front woofer, and then to the rear woofer’s supplementing of the front, were utterly seamless — which hadn’t been the case with the B1s.

So, unlike with the B1, I have no caveats about the Oval B1 Decade’s bass — except that the B1D didn’t have much bass output below about 40Hz. This shouldn’t be surprising from a speaker with just two small woofers in a fairly small cabinet — the B1D hinted at frequencies in the bottom octave of the audioband that it just couldn’t hit……

(Full-range requires bass extension to 20Hz, the bottom of the audioband, at output levels that match the upper bass, midrange, and above.)

Of course, Vivid’s Giya G2 can also reach lower than the B1D — down to at least 30Hz, also with tremendous authority. That’s where the B1D mostly fell short of the G2: in the deep bass. And when push comes to shove, I believe the G2 can play a bit louder than the B1D….

…The B1Ds’ sound held together fine under such punishment, but in some extremely loud passages I could sense I shouldn’t push them further — the subtlest hints of high-frequency compression and hardness were setting in, signs that if I turned them up much louder, serious distortion and/or compression might arise. I remember playing the Giya G2s louder and louder and louder and never hearing any strain — I stopped pushing any louder only because no one in his or her right mind would listen at those levels. Turning it up until I broke something didn’t seem the prudent thing to do.

But the Giya G2 costs $50,000/pair — $22,000 more than a pair of B1Ds — and from what I can recall of its sound, it truly betters the B1D only in low-frequency extension and maximum output capability.

Conclusion

When I heard that Laurence Dickie had begun revising Vivid Audio’s Oval B1, I didn’t think he’d be able to make much of an improvement. But the Oval B1 Decade doesn’t sound only a little better than the original model — it sounds so much better that it now stands alongside Vivid’s very top models, the Giyas, all of which cost much more (and for some rooms, a pair of B1Ds might be the better choice). When I spoke with Dickie after returning the review samples of the Oval B1 Decade, he confessed that even he had been surprised at the magnitude of the improvement. For those who value the sonic qualities of Dickie’s speaker designs, such as unrivaled clarity and openness, the Oval B1 Decade is well worth the not-inconsequential $10,000 increase in price. In short, it’s a complete success.”