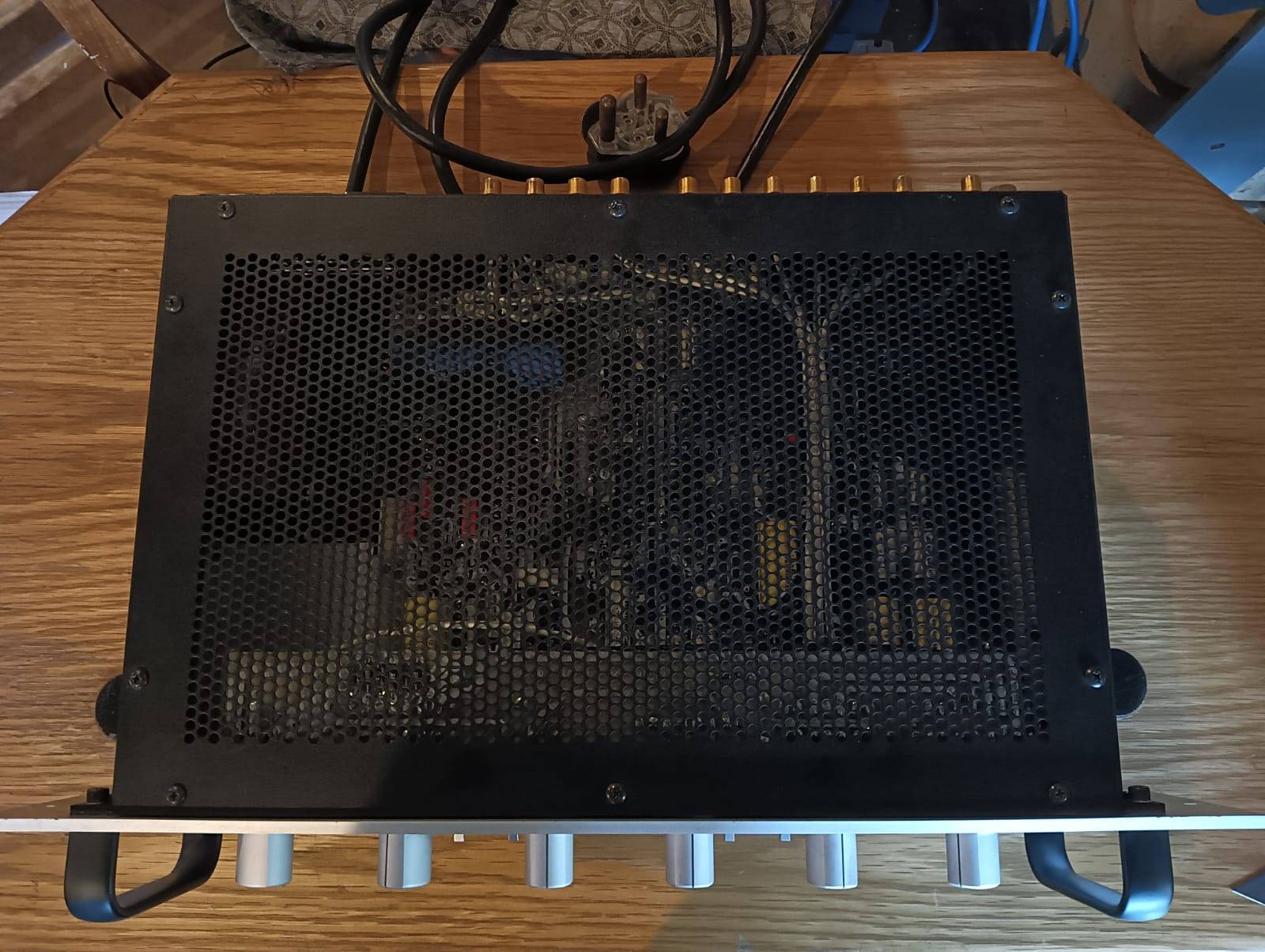

Audio Research SP14 Preamplifier

Original price was: R68,000.00.R23,000.00Current price is: R23,000.00.

Specs:

FREQUENCY RESPONSE

High level section: ±.5dB, 5Hz to 50kHz, -3db points below 1Hz and above 200 kHz. Magnetic phono: ±.3dB of RIAA, 30Hz to 40kHz

DISTORTION (THD)

Less than .01% at 2V RMS output

NOISE & HUM

High level: (1) 70 µV RMS maximum residual unweighted wideband noise at main output with gain control minimum (98 dB below 5V RMS output) (2) More than 100dB below 1V RMS input (less than 7 µV equivalent input noise). Phono: 0.12 µV equivalent input noise, IHF weighted, shorted input (78dB below 1mV input).

GAIN

Phono input to tape output: 46 dB. Phono input to main output: 66 dB. High level inputs to tape output: 0 dB. High level inputs to main output: 20 dB.

INPUT IMPEDANCE

Line inputs: 50 K ohms. Phono: 47K ohms (provisions for any value below 47K ohms or added input capacitance for matching certain magnetic cartridges.)

OUTPUT IMPEDANCE

250 ohms main output, 1000 ohms recorder output. Recommended load 60K – 100K ohms and 100pF. (20K ohms minimum and 1000pF maximum)

MAXIMUM INPUTS

Magnetic phono, 200mV at 1kHz (1000mV RMS, 10 kHz). High level inputs essentially overload-proof.

RATED OUTPUTS

2V RMS 5 Hz to 50 kHz, all outputs; 60K ohm load (main output capability is 50V RMS output at .5% THD at 1kHz into a 100K ohm load with 5V RMS high level input)

POWER SUPPLIES

Electronically-regulated low and high voltage supplies and electronic decoupling. Shielded toroid transformer. Line regulation better than .01%.

TUBE COMPLEMENT

(1) 6DJ8/ECC88

POWER REQUIREMENTS

100-135VAC 60Hz (200-270VAC 50/60Hz) 60 Watts

OTHER

Hybrid FET/Tube audio circuit, solid-state power supply. Inputs (7): Phono, C-D, Tuner, Video, Spare, Tape 1, Tape 2. Outputs (4): (2) Main, (2) Recorder. Controls (6): Gain, Attenuation, Balance. Mode, Record Out, Input. Switches (8): Power, Outlets, Bypass, Mute, Copy, Tape 1 to 2/2 to 1, Tape 2/1, Monitor.

DIMENSIONS:

19” (48 cm) W x 5 ¼” (13.4 cm) H (standard rack panel) x 10 ¼” (26 cm) D. Handles extend 1 ⅝” (4.1 cm) forward of front panel. Rear chassis fittings extend ⅞” (2.3 cm)

WEIGHT

12 lbs. (5.5kg) Net, 21 lbs. (9.6 kg) Shipping

Age:

This model was available in the late 1990’s

Description

The name “Audio Research” will be familiar to many readers of this magazine. It belongs on the list of that select group of manufacturers who continue to offer the audiophile and music lover equipment which enables him or her to truly enjoy the muse. With equipment of this caliber, one is no longer caught up in the anxiety-inducing process of listening to (evaluating) the equipment used in the presentation of the music. Instead, the listener can focus attention on the much more important message uncovered in the music via the performance and conveyed through the network of transducers, cables, tubes or FETs, more cables, more tubes or FETs, and more transducers, to the brain. If this process has been successful and our sensitivities heightened, our souls will be touched.

If not, not. In my experience, the electronics offered by Conrad-Johnson, Mark Levinson, Quicksilver, and Audio Research have achieved this most perfect synthesis of technology in the service of music. Each of these companies offers products which force a reviewer to search for new words to help communicate to the reader a quality of sound reproduction which transcends excellence. The SP14 preamp is such a product.

The last Audio Research product to grace the pages of Stereophile was the original SP9 preamp, which got a rather lukewarm review at the hands of both J. Gordon Holt and John Atkinson (Vol.10 No.8). That was 2½ years ago! A follow-up to that review is in progress; only the flagship SP15 preamp now remains a stranger to Santa Fe.

The SP14, being a single-chassis unit, shares an outward appearance with the SP9 Mk.II, albeit with half again as many knobs and twice the number of toggle switches. Retailing for $1200 more than the SP9 Mk.II and just half of the SP15’s $5995, it occupies an increasingly volatile market niche, with strong competition from both this country and abroad. The SP14 is a hybrid design, and follows in the tradition of the SP9 Mk.II in using one 6DJ8 dual-triode vacuum tube in an intermediate gain stage of the phono section. The line section is all-FET, using a circuit similar to that in the SP15.

The onboard power supply features extensive electronic regulation for both low and high voltages and an excellent, shielded toroidal power transformer (located at the rear of the left-hand sidewall so as to be as far away from the sensitive phono circuitry as possible). Construction quality is first-rate—just what we have come to expect from ARC. Ergonomics are also excellent, with highly legible markings identifying intelligently placed controls. I appreciate the fact that no squinting is required to read the black lettering on the silver front panel. (I wish more companies would adopt this style. I’m getting tired of the ubiquitous black with gold lettering. For those who want black, however, Audio Research components are available, at extra cost, with anodized black front panels and knobs with silver-gray lettering.)

One characteristic which distinguishes the SP14 from the SP9 Mk.II is the degree of control flexibility offered. For starters, it has separate gain and attenuation knobs for optimization of the signal gain setting. Separate input and record output switching offers the listener the opportunity to listen to one source while recording from another. Perhaps most important, the SP14 incorporates a bypass switch which directly connects the attenuation knob and gain control to the source selected by the input selector. All other controls and switches are removed from the active signal path when this switch is thrown. Note that, unlike other competing designs, this configuration applies to the line inputs as well as to the phono stage. There are two separate sets of outputs (for ease in bi-wiring) and three convenience AC outlets.

Six knobs grace the front panel. From the left is Gain, a stepped control which normally should be used around the 12 o’clock position, the main volume level being set by the Attenuation knob next to it. This provides 6dB of attenuation in each of four increments (–6, –12, –18, and –24dB). Using these controls makes easy the optimization of input levels relative to output. The next knob is the Balance control, also stepped. Beside it is a control which I feel essential to any high-end or other preamp—Mode. In addition to stereo, this control provides the all-important mono position, which will eliminate the pseudo-stereo effect in early-’60s reissues of recordings originally recorded monaurally. This control will also reverse the stereo channels and send either left- or right-channel information to either channel as selected. Next is the Record Out selector, which shares a menu with the Input selector. Input source selection is provided for Phono, CD, Tuner, Video (!?), and Spare. With separate inputs and outputs for two tape recorders, I feel the SP14 will offer all but the most obsessed enthusiast more than enough source selections. Independent control of these functions is a handy feature, though purists may look at it scornfully.

Below the control knobs are two sets of sturdy toggle switches. To the left of the green LED are Power, Outlets, Bypass, and Mute. The Outlets switch controls power to the three grounded receptacles on the rear panel. Two of these are switched, the third unswitched. I did not use these convenience features during the course of my audition, though, preferring a separate, computer-grade protection device such as Data Shield’s Model S85. The Mute switch is not only handy when listening must be interrupted, but helps safeguard the power amp and speakers from unexpected transient signal surges. I activated it each time I changed signal sources. In Mute position the green LED glows faintly, returning to full brightness when Mute is disengaged. The Bypass switch, as mentioned earlier, provides essentially a “straight wire with gain” conduit for either line-level sources or phono. All of my serious listening was done with the Bypass switch on.

The other four toggles deal with taping. Bidirectional dubbing can be accomplished with ease, even while listening to another program source. Source/tape monitoring is done with the flick of a switch.

The only features missing on the SP14 (found on the SP15) are absolute phase, phono high-pass filter, and front-panel impedance selection for cartridges. This last can be accomplished on the SP14, though, with a little soldering. I asked Audio Research about this somewhat awkward arrangement for optimizing cartridge loading; they feel that in a product at this price point, a hard-wired connection is the best compromise, in terms of mechanical stability and signal quality, between various pin-socket arrangements and the expense of a precision, gold-contact switch (as is found on the SP15). Unless you’re a compulsive cartridge swapper, I feel this inconvenience to be minor. My sample was loaded for 100 ohms for my AudioQuest 404i-L cartridge.

The rear panel of the SP14 is neatly laid out with solid, gold-plated jacks. In traditional ARC manner, the right-channel sockets are above the left-channel ones.

Listening

With the system settled and the preamps cooking, I went about the task of selecting LPs and CDs to use in my evaluation. As I was to find out soon enough, this was not going to be an easy task. It’s not that I didn’t have enough source material at hand—I did. What I found happening was that with electronics of this caliber, I often sat mesmerized by what I was hearing. My yellow pad remained void of listening notes as I became lost in the music. I wanted to remove my critical listener’s hat and just enjoy the opportunity to hear—really hear—many of my favorite recordings as if for the first time.

Each of the preamps I listened to unlocked nuances in the performances which had heretofore gone unnoticed. The question remaining for me to answer was which of these preamps I felt most comfortable with in terms of my own perceptions of the music they presented. Would the sound quality of, say, the Conrad-Johnson PV9 outweigh its lack of features? Would the Classé DR-6 sound as good as it looked? Would the SP14 carry on the enviable reputation its manufacturer has earned? Which of these preamps would I buy if I was pressed to make a choice?

Answers to these and other questions were slow in coming; I felt myself falling into reviewer’s angst. A healthy dose of Zydeco, as performed by Clifton Chenier on his album Bogalusa Boogie (Arhoolie 1076), saved me from the gloom, and I returned to my assignment with renewed enthusiasm.

The first couple of cuts on the Chenier album (a must for anyone interested in good-time music) proved enlightening in this evaluation. The album is not an audiophile release by any stretch of the imagination, yet there are moments when the recorded sound causes one to sit up and take notice. As I listened over and over to the tunes through each of the preamps, I began to notice subtle differences in the way each handled the sound.

Cleveland Chenier playing the rubboard, for instance, was clearly standing in front of the drummer to the right of center when heard through the SP14. The spatial relationship between the two musicians was obvious, and I could perceive a certain amount of “air” around each musician. The Classé DR-6 did not make this spatial separation as obvious; both musicians seemed to occupy the same space. The PV9 maintained the spatial information but failed to resolve the timbral characteristics of the two percussion instruments. It was sometimes difficult to tell which rhythm was carried by the drummer playing the cymbals, and which was provided by the rubboard. The SP14 clearly differentiated the damped, metallic sound of the rubboard from the undamped, metallic sound of the cymbals, making it easy to follow their individual rhythms. The overall sound of the rubboard took on interesting characteristics when heard through each preamp. The Classé gave the instrument a brighter, more “tinny” sound (no derogatory connotation intended). It’s as if the sound was radiated directly off the ridges in the corrugated metal, with no sensation of the body of the instrument (which hangs down like a vest over the player’s chest).

In contrast, the SP14 gave me the impression of the entire instrument as it was played: the clear, ringing sound of the scraper as it is drawn over the corrugations in the metal, as well as the fuller, less resonant sound of the metal vest itself. The PV9 stood somewhere between the ARC and Classé preamps in its ability to convey this information: more pleasing to my ears than the Classé, yet not as convincing in reproducing the unique timbral nature of the instrument as the SP14. Each of the preamps served this music well; soundstaging and low-level resolution were exemplary on each. The PV9 and Classé injected a stronger bass to the performances, making the SP14 sound, in comparison, subjectively somewhat lightweight. However, as I listened repeatedly to the tunes, I felt most comfortable with the way the SP14 presented the music. It sounded “right” to my ears with each instrument, sharply focused in space on a well-defined soundstage, clearly resolved with its unique timbral qualities. Accordion, harmonica, Clifton’s voice, Cleveland’s rubboard, John Hart’s tenor sax, the guitar, bass, and drums, all sounded “real” to me, reproduced with an ease and naturalness which I have not heard before in my system. Needless to say, there was a lot of foot-tapping and head-bobbing as I listened to the music!

Turning to music of a different culture, I cued up an early album by the Bothy Band (Mulligan LUN 007). The second song on side 1, “Fionnghuala,” features a goosebump-inducing acappella vocal ensemble. The treatment of the male vocals through each of the preamps was as I had expected based on previous listening: the Classé endowed the voices with a somewhat lean character; the chestiness which usually accompanies the male voice seemed attenuated; individual vocal nuances of each singer were not as well identified with the Classé as they were on either the PV9 or SP14; overall, a more homogeneous sound—good, but lacking that last degree of finesse and believability. The PV9 excelled on this cut, giving me a very “lively” performance with perhaps the widest soundstage of the three. Subtle dynamic changes were perceived clearly; this quality, coupled with an excellent rhythmic flow, caused me to become actively involved with the performance. If the PV9 had communicated more of the chestiness of the voices, it would have been a dead heat between it and the SP14. It didn’t, though, and I once again preferred the sound of the ARC product. Each voice through the SP14 had that unique quality which made it clear that a group of men was singing, spatially separated.

The third song on the side features an instrumental ensemble in a lively tune called “The Kid On The Mountain.” (The flute playing of Matt Molloy is exceptional, as usual.) On this cut, the flute’s sound was captured differently by each preamp. The Classé gave an overall lighter sound to the instrument, with a noticeable lack of air. The performance lacked rhythm, and subtle dynamic changes were hard to perceive. The PV9 corrected most of these failings, yet did not capture my fancy as strongly as did the SP14. The air around the flute was palpable through the SP14. I could sense the column of air vibrating through the instrument as it was played, as well as the ambient space around the performer. This cut was particularly ear-opening, as it helped me formulate my initial impressions of each of these preamps.

The Classé did not sound like the solid-state product it is. Quite the contrary, it sounded more “tubey” than the C-J PV9: a dark sound with a light footprint. The PV9 impressed me with its truthfulness. It was not shy in presenting the music (sounding more solid-state than I would have imagined), yet maintained the magic heard through the best tube products. The SP14 transformed my expectations as to what can be achieved in sound reproduction at this price level. It did everything well, combining the positive aspects of the Classé and C-J into one musically involving component. At the same time, it added an element of its own, which I can only describe as a naturalness in the rendering of the often diverse elements making up a performance. Be it vocal or instrumental, popular or classical, each musical selection heard through the SP14 caused (in some instances forced) me to put down my pencil and yellow pad to listen. It was that involving.

Again changing musical gears, I slipped a Columbia recording of Charles Ives’s String Quartet No.1, performed by the Juilliard Quartet (MS 7027), onto the turntable. With the SP14 in the chain, I was immediately immersed in some of the finest, warmest sound I have ever experienced from this record label. Perhaps this recording is an exception, but I usually have had to adjust my ears to the often strident, acoustically dead sound of Columbia Masterworks. The sound I heard here was different, though. The quartet literally “breathed,” with outstanding instrumental timbres captured in a fairly “roomy” acoustic setting. Especially enjoyable was the sound of Claus Adam’s cello. It maintained the woody quality I have come to associate with this instrument, while providing me with ample clues as to its resonating character. The sound was round and full, and I clearly perceived the “rosin on the bow.”

It’s enlightening to me that, as my system improves, I am able to enjoy recordings I had previously given up as hopeless. Even in the grooves of these old recordings there is beauty which can be retrieved, converted into musical signals, and enjoyed. Such is the case here, much to the credit of ARC. The performance conveyed the emotion released through the music in a fine manner, at one point reducing me almost to tears. The beginnings and ends of the notes were not confused, and the important rhythmic flow was not interrupted. Compared with the sound with the Classé in the system, it was as if several veils had been lifted, enabling me to easily approach the music. The Classé coated the music with a syrupy texture, the cause of which I hesitate to guess. Perhaps it has to do with the DR-6’s timing. All I know is I felt uncomfortable with what I heard. The sound reminded me of what I remember this recording to be before system improvements. An anomaly? Perhaps. Or is this indicative of something more significant?

The PV9 again acquitted itself splendidly in presenting the music on this recording. The soundstaging was excellent, with good depth and width. I could visualize the four performers sitting in a semicircle just in front of my speakers, violins on the left, viola and cello on the right. The body of the cello had the correct resonating character, and it was easy to hear the attack of the bow on the strings. Each instrument had its unique sound, with the correct timbre. Yet, as I listened to the entire piece, I fell back on the sound of the SP14. It was not as seductive as the PV9, but offered that hard-to-define sense of “naturalness” which escaped my perception while listening to the other two units. I just could not imagine anything sounding better in the way of music reproduction. I threw everything I had in the way of vinyl at the SP14—45s, mono LPs, stereo LPs, dance singles, pseudo-stereo LPs, audiophile and non-audiophile recordings. In each instance, I sat spellbound by what I heard, not wanting to get up to do anything else. Quite satisfied with the performance of the SP14’s phono section, I put my records aside and reached for my favorite CDs to listen to its line stage.

The first CD to be inserted in the CAL player was the Astrée Sampler (E 7699), a disc I urge every reader with a CD player to purchase. The music is varied, the sound is, almost without exception, marvelous, and it has served me well as a reference disc. The most striking thing I noticed when I began comparing the line stages of the three preamps was that, with the Classé and C-J, the sound quality was the opposite of what I had heard through their phono stages. In other words, the line stage of the Classé approaches the best, overshadowing the limitations I had perceived through its phono stage. Similarly, the line stage of the C-J fell somewhat short of its exceptional phono stage. The SP14, however, did not disappoint me. The sound quality of its line stage was equal to that heard through its phono stage. In short, excellent! Here, at last, was a component which could hold its own with any of the competition, not needing help from any outboard devices. Track after track on the Astrée CD revealed a musical experience which I had only read about before.

Now this experience was being communicated to me and my listening companions in my own room. From the delicate filigrees in John Dowland’s lute Fantasie to the subterranean organ stops in the De Grigny, the SP14 uncovered nuance after nuance in the web of the music. The buzzing tonality of Blandine Verlet’s harpsichord in the Couperin stood in stark contrast to the growling bass viol of Jordi Savall in the Tobias Hume, exquisitely captured with every detail intact. I never felt uneasy with what I heard. I could finally listen through the electronics to the music itself. Thoughts of bass extension, treble roll-off, midrange warmth, direct/indirect sound, etc., did not even enter my mind. Audiophile jargon seemed out of place now, being replaced by discourse related to the music. I related to the music in terms borrowed from the arts instead of from electronics. I was able to breathe a sigh of relief, releasing the pent-up anxiety one stores inside when allowed to relax in the presence of the real thing. The feeling was delicious!

A CD I turn to often for purely musical enjoyment is the recording of Ariel Ramirez’s Misa Criolla, featuring the tenor, José Carreras (Philips 420 955-2). The musical forces include a large mixed choir along with an ensemble of South American flutes, pan pipes, guitars (charangos), and percussion. The soloist is centered on the stage with the choir spread out behind him. Further back and to the left side of the stage are the large drums and other percussion instruments. The sense of space captured on this recording is outstanding; the drums, in particular, seem placed against the back wall of the church, many feet behind the choir. The sound of those drums reverberating off the side and rear walls is spectacular. The PV9 was the champion in soundstage presentation on this disc. The sense of spaciousness it conveyed was unmatched by either the SP14 or the DR-6. In fact, if it were not for the slight accentuation of the sibilants of Carreras’s voice and an overly obvious rendering of breath intakes among choir members, I would say that the C-J, on this disc, was the leader of the pack.

And yet, there it was: a slight coloration, a tilt in the response curve perhaps, which over a period of time I perceived as an etched quality. Despite this, it was obvious that there was a body attached to the solo voice. The character of that voice seemed just about perfect, with the right combination of chest and throat. In contrast, the Classé seemed to thin out everything on this recording, including the body supporting Carreras’s voice. The choir behind the soloist seemed disembodied, merely voices emanating from a point behind him. The SP14 gave the soloist’s body back as well as the choirs. Individuals with their feet on the ground (or risers) once again accompanied Carreras. The SP14 warmed up the sound a bit compared to the PV9, yet I never felt I was missing any information or detail as a result. I only heard a less colored rendering of the music.

At this point in my listening session I decided to retire the Classé DR-6 preamp and concentrate on the differences I was hearing between the SP14 and the PV9. These two units seemed to share a similar quality which the DR-6 lacked—magic. Whether you prefer the type of magic served up by the PV9 or the slightly different magic offered by the SP14, I feel it important to spell out the differences as I heard them in my system.

Jennifer Warnes has a magnificent voice, showcased on the CD Famous Blue Raincoat (Cypress YD 0100/DX 3182). I was only able to get the A&M reissue of the original, so please bear with me. (I’ve heard the original, and agree that it is significantly better. If any of our readers know where I might find a copy, please let me know.) The title tune begins with a tenor sax and bass duet which the PV9 gets absolutely right. The sax sounds as real as any I’ve ever heard, and the string bass has the heft and body I associate with the instrument. It’s a marvelous introduction to a song which will grow on you with repeated hearings. The mystery (magic?) wears off, though, when Jennifer comes in on the vocal. Her voice has a slight edge which I do not hear on the SP14. As a result, she seems too forward in the soundstage, as if she is about to embrace you. Not that this would be an unpleasant thing, but I prefer the more seductive sound of Ms. Warnes sans the edge (I like to use my imagination).

Alas, with the attenuation of the edge on the voice, the SP14 loses something in the rendering of the sax and string bass. They just don’t seem as real. In the next track, the edginess on both Leonard Cohen’s and Jennifer’s vocals becomes downright irritating on the PV9, much less so on the SP14. Listening to this cut, I felt as if I’d uncovered a dilemma in my own perception of what I hear. On the one hand, I liked what I heard through the C-J—up to a certain point. Beyond that point, I preferred the sound of the ARC. The dilemma is that the point is never constant, varying from recording to recording. So I must make a compromise in my expectations and in my recommendations.

Conclusion

As far as value goes, I have to say the ARC SP14 represents the better investment. It has most, if not all, of the features the audiophile will want. It has control flexibility which the C-J PV9 doesn’t even approach. It’s as well made as any component I’ve had the pleasure to review, and is backed by a company whose reputation for good sound and quality products is legendary. In my opinion, the sound of the SP14, via line or phono, will set new standards for the industry. I can see other companies using the SP14 as a benchmark by which to judge their own products—it’s that good. It is user-friendly and attractively styled, injecting its unique form of magic into the reproduction of music to a degree I’ve rarely experienced before. I feel it should be included in Class A of “Recommended Components.” It is a very special product.

But so is the C-J PV9. In its own way, the PV9 also adds an element of magic to our enjoyment of a musical event. Its soundstaging is beyond reproach; its ability to retrieve the finest detail in complex passages is uncanny. It is made to reproduce saxophone, string bass, male and female voice. It is convincing in its ability to portray the weight and presence of a large ensemble. Yet, to me, it doesn’t represent a particularly good investment. Its lack of a mono mode switch alone eliminates it from my want list. I need control flexibility and provision for optimizing cartridge loading. Not all cartridges sound best loaded to 47k ohms (though my AudioQuest didn’t seem to mind). It is a minimalist design with minimal features. If you don’t need or want the control offered by the SP14, this could be the preamp of your dreams. Soundwise, keeping in mind my uneasiness with the line stage, it takes a back seat to no other product within its price range. I agree with its placement in Class B.

What started out as a single product review has turned into an unqualified recommendation for one product, a qualified one for another. When I was given the SP14 for review, I thought my task would be easier, with a clear-cut winner. I was mistaken, and perhaps a bit naïve, to so assume—it’s never as easy as it seems. However, if my examination of either of these products has stimulated your interest, I urge you to try each out in your own home in your system. Insist on this when talking to your dealer. Only then will you come under the spell of the magic cast upon the listener by these products. And only then will you know whether you like your music with (C-J) or almost without (ARC) tubes.