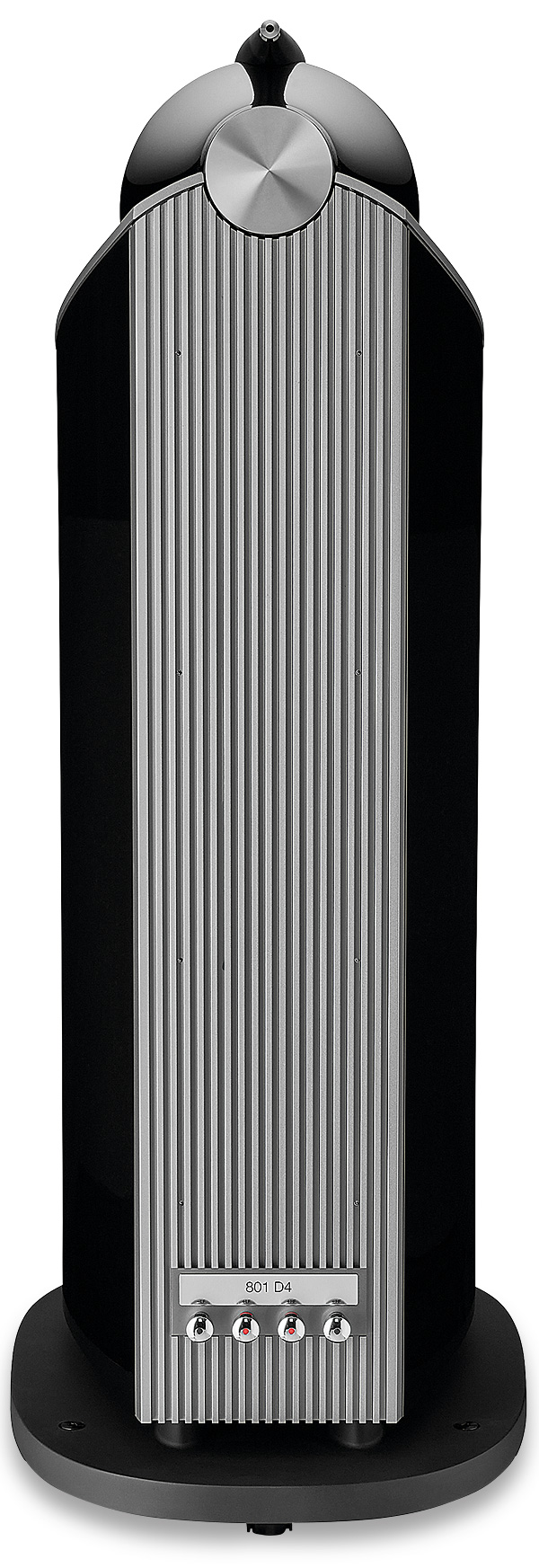

Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4 [Piano Black]

Original price was: R980,000.00.R820,000.00Current price is: R820,000.00.

These speakers are basically NEW, only 8 months old. Bot even properly run in!!! Save some serious money!

Specs & Pricing

Type: Three-way dynamic loudspeaker system with a top-mounted tweeter, Turbine Head midrange enclosure, and downward ported bass enclosure.

Driver complement: 1″ diamond dome tweeter, 6″ Continuum cone FST midrange, two 10″ Aerofoil cone woofers

Frequency response: 15Hz–28kHz (±3dB)

Nominal impedance: 8 ohms

Sensitivity: 90dB

Dimensions: 17.8″ x 48.1″ x 23.6″

Weight: 222 lbs.

Price: $35,000

Description

When the Bowers & Wilkins 801 loudspeaker first saw the light of day in 1979, it was immediately received with enthusiasm by discerning audio hobbyists and recording professionals alike. Famously, EMI’s Abbey Road facility adopted the speaker as its reference monitor, and other studios followed suit. The original was a bit clunky-looking: a dimple of a tweeter perched atop a breadbox-sized midrange module that sat on a much larger, squarish bass enclosure. The visual effect, to me at least, was that of a wedding cake gone wrong. The latest iteration of the 801, the D4, is now available and, while the appearance is far more elegant than its earliest progenitor, an observer transported from 1979 to the present would have no difficulty identifying the 801 D4 as a direct descendant. The 801’s most basic design principles have been preserved, but also advanced and refined over four decades of continuous consideration by the engineers at B&W. That, by the way, was the last time I’ll be using “B&W” in this review. When I used it, repeatedly, in an email posing questions to the manufacturer, I got back the kind of firm but polite rebuke that only the Brits can muster. “Please note the name of our brand is Bowers & Wilkins, not ‘B&W,’” wrote Andy Kerr, the company’s Director of Product Marketing and Communications. “We moved away from using ‘B&W’ over a decade ago.” I felt like I was around twelve and a parent/teacher conference was in my immediate future. I promise the term will never pass my lips again.

In a real sense, it was the original 801 that was the “revolutionary” product in this loudspeaker’s extraordinary run of 43 years (thus far). The use of computer modeling and what the company called “numerical optimization” to develop the crossover network were largely unheard of at the time, and the use of separate enclosures for the treble, midrange, and bass transducers, appearance be damned, was novel as well. The three subsequent generations of 800 Series loudspeakers that followed had a sonic heritage to build upon, a design and manufacturing tradition that would readily accommodate—embrace, really—new developments in measurements, materials, and production methodologies. Pretty much everything inside and outside the flagship 801 D4 is different from the original loudspeaker of 1979, but the basic engineering concepts and sonic character are not. Note the reference to the 801 as Bowers & Wilkins’ “flagship” product. What about the sculptural Nautilus, still very much in production and costing $25,000 more than the $35,000-per-pair 801 D4s? Andy Kerr left no doubt as to the company’s view of the hierarchy. “Regarding Nautilus: It’s a beautiful, great-sounding, and iconic loudspeaker, for sure, but it’s not the best we make. It’s been surpassed in a few key areas by newer generations of loudspeaker technology. The 801 D4 is, without question, our flagship model.”

The “D” in the model number refers to the diamond material used to form the 1″ dome tweeter’s diaphragm in all the 800 Series speakers, a technology introduced in 2005 that results in an extraordinarily high first-breakup frequency of over 70kHz. The housing for the free-mounted tweeter is still milled from a solid block of aluminum but its shape is now different, and there’s a longer tube-loading apparatus, nearly twelve inches in length, that the manufacturer feels is responsible for a more open top end.

Bowers & Wilkins goes to quite extraordinary lengths to mechanically isolate the proprietary Continuum FST cone that’s responsible for midrange reproduction from the rest of the speaker. The all-aluminum housing for the 6″ midrange transducer, referred to as the Turbine Head, is exceptionally rigid and internally damped; the driver assembly itself “floats” at the end of a spring mounting rod, secured in front by six silicone decoupling points. For the D4 iteration, Bowers & Wilkins has introduced what it calls the Biomimetic Suspension system to improve the mechanical behavior of the driver’s fabric spider, a critical component of dynamic transducers that connects voice coil to basket. The new technology is meant to prevent the spider from generating air movements independent of those the Continuum cone is supposed to be producing, and thus to eliminate a source of potential distortion.

A pair of 10″ Aerofoil woofers, vented towards the floor via the company’s Flowport, completes the 801 D4’s driver complement. They feature a new anti-resonance plug in the voice coil, designed to reinforce the voice coil and prevent it from flexing.

The 801’s enclosure has come a long way in performance and appearance since the utilitarian boxiness of the first edition. A gentle roundness dominates the visual presentation. The front and sides of the speaker are fabricated as a single, continuous curve—a “reverse wrap”—that attaches to a solid aluminum spine behind. Having a curved front means there is less baffle around the woofers, resulting in improved dispersion and reduced reflections. Bowers & Wilkins has long employed an internal Matrix construction, a system of interlocking plywood panels configured with foam-filled cells in two perpendicular planes that help assure a resonance-free cabinet. The D4 iteration of the 801 has fewer of the panels, but adds strategically placed aluminum braces glued and bolted into position. New for the 801 D4 is an aluminum plate around the downward-facing Flowport. An aluminum top plate, also new, further increases the stiffness of the speaker’s cabinet and helps with decoupling the midrange and tweeter elements from the large compartment below.

The crossover can be considered “external,” as it’s attached to the inner surface of the aluminum spine at the rear of the speaker. The crossover frequencies, Kerr informed me, were “roughly” 350Hz and 4kHz. Premium electronic components from Mundorf, Powertron, and Angelique are used for the network. At the rear of the 801 D4s are 5-way binding posts—two sets, to allow bi-wiring or bi-amping.

The loudspeakers come with very substantial grilles for the midrange and the two bass drivers, cloth-covered metal-mesh structures that attach magnetically. They are surprisingly transparent. Placing my ear near the Turbine Head and moving the grille for the midrange cone in and out of position didn’t change the character of the soft hiss emanating from the driver. Leaving the grilles in place could make a big esthetic difference to the non-audiophile in your life, and one shouldn’t fear that there’s any serious sonic compromise to doing so. The 801 D4s are available in four standard finishes—gloss black, white, satin rosenut, and satin walnut. In another move to up the luxury quotient of the 801 D4s, the surface beneath the Turbine Head now has a soft leather covering, sourced from a British firm (Leather by Connolly) that supplies this material to automotive manufacturers.

The 801 D4 has an integral all-aluminum plinth; the previous generation used a zinc-aluminum alloy. Bolted to the undersurface of the plinth are four wheels that allow the owner to move the speakers, once unpacked, into their approximate room position for fine-tuning their setup. Once that’s been accomplished, built-in spikes—considerably more robust than the D3’s—are lowered using a supplied tool. In the process, the wheels are lifted off the floor. (If desired, one can remove the wheels with an Allen wrench—definitely a two-person operation. This may be mandatory if the 801s are sitting on an especially thick carpet.) The spikes have metal cups attached, but they are readily removed if the speaker is sitting on a carpet.

The 801 D4s are heavy, bulky loudspeakers. Like many other large speakers, they are thoughtfully packed, both to protect the product from the rigors of shipping and—theoretically—allow an end-user to unpack the 801s himself by following the instructions printed on the outside of the cardboard boxes. Don’t do it. Like many things in life, from replacing the turn-signal bulb in a German car to intimate relations, it’s accomplished much more effectively after you’ve done it a few times, and, of course, you’re probably not going to be undertaking this procedure terribly often. Let the dealer unpack them and get them near to their final destination, even if there’s a charge involved. It’ll be better for all the fingers, backs, and parquet floors involved.

The Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4s ended up located where most large dynamic loudspeakers do in my 15′ by 15′ room, especially when there’s no rear-firing port. They were positioned about two feet from the CD-lined wall behind them, approximately eight feet apart and eight or nine feet from the listening position. The associated equipment utilized for this review is listed in the sidebar.

The first music I listened to through the 801s, even before final positioning and spiking, was my go-to reference symphonic selection for equipment assessment, a 2010 RCO Live recording with the late Bernard Haitink conducting the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 15, specifically the opening movement. I was impressed right out of the gate. Many instruments get a turn in the spotlight as soloists—violin, string bass, piccolo, bassoon, trumpet, xylophone, etc.—and all were properly scaled and tonally believable. These large and imposing loudspeakers were light on their feet, uncovering the full range of detail and dynamic nuance that characterizes this recording. As I moved on to other music, the 801s continued to delight with their revelatory coherency. Not a clinical or sterile sort of clarity, mind you, but one that served musical meaning.

As a dyed-in-the-wool Steely Dan fan, I’m a little embarrassed to admit to missing, until quite recently, a two-CD set released in 2006 titled Maestros of Cool. It’s what you’d call a “tribute album,” with covers of 20 SD songs by a variety of artists with musical styles ranging from indie pop to jazz to hip-hop There are also several original songs intended to channel the essence of Becker and Fagen’s creations, the best of which is “Remember” from a band called SteReO. All the tropes are there—the unpredictable jazz-flavored chord progressions, elliptical lyrics, the rhythmic hitches and pauses that set up memorable hooks and refrains. But what makes the song truly an homage are the arrangement and production—the loping bass, the keyboard and guitar filigree, the commentary by unison trumpet and sax, the way the backup singers support the lead vocal as economically as possible, the wheezy organ that wanders through the mix. All these details that matter so much to the musical success of the song are laid out in sharp relief. This is due, of course, to the meticulous engineering and mixing of the recording—but also to the transparency and coherency of the 801’s presentation.

The Bowers & Wilkins product is also revealing in a nerdy audio sense. They will tell you what you need to know, like it or not, about the rest of your stereo system. Cables, for instance. Establishing which wires work best with an unfamiliar loudspeaker can be a tedious undertaking that leaves one doubting his judgment after an hour or two. It didn’t seem that way with the 801 D4s. I tried my usual Transparent Ultra speaker cables, which bested a single pair of T+A Speaker Hex cables. However, bi-wiring with two sets of the T+As was best of all and, for once, there wasn’t a great deal of agonizing involved in the assessment.

This very positive appraisal duly registered, it’s time to address a potentially consequential issue, namely the demands the Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4 makes on the amplification preceding it in the audio chain. During my first weeks with the 801s, I remained enthralled by the way they uncovered the basic nature of all stripes of music they encountered—but also began to sense a lack of control and “grip” with dynamic source material. I’m not just talking about grand opera and headbanger metal; a well-made solo piano recording could also alert me to the issue. My 60W Pass XA 60.8 monoblocks were clearly falling short; substituting the 200Wpc David Berning Quadrature Zs got better results, but I was still “leaning in” to fully engage with the music.

This isn’t a new observation, by any means. The 801s have long had a significant impedance drop from the upper bass to the middle midrange. Although Andy Kerr explained that the D4 version of the speaker was “somewhat kinder than the D3” in this regard, it still requires a lot of power, and the right kind of power, to perform at its best. I’m certainly not a measurement kind of audiophile—my skills are rudimentary, and my engineering background is nil—but I do have a Dayton Audio OmniMic V2 system that I use for taking measurements from the listening position to optimize subwoofer integration and to at least take a look at the in-room frequency response of the loudspeakers here for review. I connected it up, played sine wave sweeps and, with the Berning amplifiers, saw an 8-to-10dB depression between 200 and 1000Hz. The lower bass was messy, as well. Clearly, I needed to hear the 801s with more robust amplification. The nearby dealer Doug White (The Voice That Is) loaned me the new Tidal Intra stereo amp that delivers 330Wpc into an eight-ohm load and 670 watts into four. The substitution of the Intra for the Quadrature Zs was transformative. The measured dip decreased to just 2-to-3dB and, subjectively, there was an obvious improvement in immediacy and control.

Employing the sort of generalizations that we audiophiles tend to make, it would be easy enough to declare that the new 801s have “good bass,” and move on to the next sonic parameter. But what does that mean? “Bass” isn’t a monolithic aspect of either music or sound reproduction, defined simply by a frequency value. There’s the bass foundation that gives “weight” to an orchestral recording, the “fat” bass on vintage Motown tracks, or the highly dimensional bass that emanates from a stand-up acoustic instrument in a jazz trio. There’s the subterranean bass generated by a synthesizer, and the full, resonant underpinning a cello provides to a string quartet. There’s tuba bass, contrabassoon bass, and even harp bass. (Andreas Vollenweider, anyone?) Of course, there’s organ bass, those 16- and 32-foot stops made of wood or metal. There are several percussive styles of playing electric bass, the stomach-churning bass heard with some hip-hop, or the sound of those extra nine bass notes on an Imperial Bösendorfer. The 801s do all these species of bass convincingly.

Perhaps counterintuitively, it’s the full-range speakers with the best LF performance that are most successfully integrated with a subwoofer to provide those last few hertz of bottom-end extension and define the volume of a large concert hall or cathedral. As noted above, the in-room frequency response of the 801’s bottom octave, with the Berning amps providing power, was wildly uneven; adding a subwoofer would have been pointless. With the Tidal Intra driving the speakers, there was a very smooth roll-off beginning at about 38Hz in my room, and it was not difficult to dial in my Magico S-Sub. (The 801 D4’s published -3dB LF specification is 15Hz, which is surely “optimistic” in most real-world listening environments.) On the (in)famous Jean Guillou recordings of César Franck’s organ music on the Dorian label, with sub activated, the music accrued more authority—a majesty that went beyond just rattling the vases in the china cabinet.

What other aspects of sound reproduction do the new Bowers & Wilkins bring off with aplomb? There’s the delineation of instrumental color—it was as easy as it’ll ever be for me to distinguish a Guarneri violin from a Stradivarius. How about dynamic shading and gradation? Listen to the “Abîme des oiseaux” movement of Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time, which has the clarinetist, unaccompanied, slowly growing the volume and intensity of several very long tones. Atmosphere? Check out the off-stage post-horn solo over muted strings in movement three of Mahler’s Symphony No. 3. The 801s are fast—they’ll keep up with the virtuosity of a Béla Fleck or Marc-André Hamelin—and they’ll render the most characteristic symphonic textures idiomatically.

The comprehensiveness of the 801 D4’s sonic strengths is apparent, I should say, even with amplifiers that don’t entirely conquer the impedance drop described above. One certainly should not conclude that there are only a few amps out there that will do the job. Just a few days after I parted ways with the review pair, for example, I heard the new 801s at Capital Audio Fest played with a pair of McIntosh MC901s, the solid-state section driving the woofers and the tube section handling the upper drivers. The results were stunning.

Unless you view the fact that the Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4s demand stout and sturdy amplification to sound their best as a demerit, they are a loudspeaker without any musically consequential deficiencies. If you listen to nothing but Renaissance recorder music, these speakers will give you a sound that’s airy, dimensional, and tonally correct. If it’s Death Metal that floats your boat, you won’t be disappointed, either—they’ll render all the slashing, bashing, and growling with as much attitude as you could hope for. Best of all, if you indulge in the Baltimore Consort in the afternoon and Cannibal Corpse after dark, the 801s won’t bat an eye.

There’s a final point that should be made. For most people, $35,000 is a lot of money for an audio expenditure. In the world of elite loudspeakers, however, that kind of outlay doesn’t get you to the middle of many manufacturers’ product ranges. The Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4s actually represents a terrific value. For your investment, you’re getting a flagship transducer with a legacy of steady, incremental improvement over time, a speaker that’s been 40-plus years in the making. Surely a classic.

B&W 801 D4 Loudspeaker

A new 800 series, and a return to the original 801 name, but the 801 D4’s enhancements are more than skin deepSome six years since the arrival of the Bowers & Wilkins 800 Series Diamond range, and over 40 years after the launch of the company’s original ‘no compromise’ 801 model [Audio Milestones, HFN Jan ’13], here we are with an all-new flagship lineup for the Worthing-based company. The timing’s about right: in the rolling programme of upgrades, we’ve seen the 600 and 700 series replaced since the 800 D3 models broke cover [HFN Dec ’15], and the company makes no secret of the fact that work started on these new 800s almost as soon as the last generation was released.

A new 800 series, and a return to the original 801 name, but the 801 D4’s enhancements are more than skin deepSome six years since the arrival of the Bowers & Wilkins 800 Series Diamond range, and over 40 years after the launch of the company’s original ‘no compromise’ 801 model [Audio Milestones, HFN Jan ’13], here we are with an all-new flagship lineup for the Worthing-based company. The timing’s about right: in the rolling programme of upgrades, we’ve seen the 600 and 700 series replaced since the 800 D3 models broke cover [HFN Dec ’15], and the company makes no secret of the fact that work started on these new 800s almost as soon as the last generation was released.

Much has changed since that 2015 launch of the 800 D3 range: Bowers & Wilkins was acquired first by Silicon Valley-based Eva Automation, then by Sound United – joining the likes of Denon and Marantz. Meanwhile, the world-famous Steyning Research Establishment has been replaced with a much larger facility at Southwater, also in Sussex.

Diamond Collection

The new 800 lineup – officially called the ‘new 800 Series Diamond’ – comprises seven models: five main stereo speakers and two matching centre-channel designs. The range kicks off with the 805 D4 standmount at £6250 a pair, and then there are three floorstanders – the £9500 804 D4, the £16,000 803 D4 and the £22,500 802 D4 – plus the two centre speakers: the £4750 HTM82 D4, designed for use with the 803 and 804 models, and the £6500 HTM81 D4, for use with the larger speakers. All models are available in a new Satin Walnut finish, as well as the Gloss Black, White and Satin Rosenut available on the previous series.

And the largest of those speakers is the one we have here – the 801 D4 flagship, at £30,000 a pair, marking a return to the model designation of the original 800 series flagship, the 801 of 1979. The last series had an 800 model, the 800 D3, as its range-topper [HFN Oct ’16], launched a year or so after the rest of the lineup arrived. Bowers & Wilkins isn’t making quite the same claims for this one that it did when launching the 800 D3, when it made clear that just about every component was new aside from the odd nut and bolt. However, even though the new model might look very similar to the 800 D3 it replaces, much has changed.

Plus ça Change

Now adopted across the board is the company’s ‘reverse wrap’ technology, in which the entire cabinet assembly, front and sides, is made as a single moulding, using thin sheets of wood laminated with glue under heat and huge pressure. This wraps round to create a tapered enclosure, terminated with a metal spine at the rear, onto which the crossover components are mounted for mechanical stability and heatsinking.

But that was already the case for the larger 800 D3 models, and not new in the 801 D4. What is, though, is a reinforced version of the company’s honeycomb-like Matrix internal bracing, again used across the range. This now features vertical aluminium sections in addition to the horizontal used in the past, affixed with screws and glue rather than the simple pressure-fit of before. Moreover, the entire Matrix frame is now coupled to the front baffle via a substantial 10mm steel plate.

All that’s internal, and thus hidden, but look a bit closer and the changes begin to reveal themselves. The top-plate of the main enclosure, on which the midrange ‘Turbine’ and treble housings sit, is now aluminium, rather than the wood of the old model, and trimmed in Connolly leather. Black is specified for the Black and Satin Rosenut main cabinets, and a light grey trim for the White and Satin Walnut finishes to match the silver Turbine Head used on those colours. Crucially, this top-plate is now a structural component, further stiffening the construction of the cabinet and the platform for the components above it.

This metal-to-metal fit allows a superior decoupling of the Turbine Head containing the 15cm Continuum Cone FST ‘floating’ midrange driver, which also gains foam wedges to the rear of its mounting, plus Techsound damping and revised Tuned Mass Dampers within. The driver itself now has a four-point silicone decoupling, and a new ‘Double Silver’ motor, with silver on the top-plate and pole, further reducing distortion. Perhaps the most radical change is the removal of the concertina-like rear suspension ‘spider’ in favour of a flexible ‘Biomimetic’ skeletal frame with thin legs that connect the cone to the basket.

The 25mm Diamond Dome tweeter atop the Turbine Head now sits in a longer milled-from-aluminium ‘Solid Body Tweeter-on-Top’ tube-loading system, for improved attenuation of rearward energy. There are now two, not three, neodymium magnets in the motor, reducing compression behind the dome, while additional vents in the voice-coil former further enhance this ‘free-breathing’ design. The decoupling between the treble tube and midrange head is also improved with two L-shaped steel mounts covered in silicone rubber.

The woofers look bigger, but the size is an optical illusion caused by the use of a new foam anti-resonance plug at the centre of each of the 25cm Aerofoil bass units. Behind the cone, the steel in the motor system has been upgraded, for better current handling and lower distortion, while single spiders replace the double units used in the old model. Finally, the bottom of the cabinet has a new aluminium plate to stiffen it around the downward-venting Flowport, and the heftier alloy plinth now has 360° spinning wheels, for easier positioning, and threaded holes that accept long spikes to adjust the forward tilt of the speaker.

![]() Gem Quality

Gem Quality

Yes, the 801 D4 may look very like the 800 D3 it replaces, but it’s almost entirely different – and its performance pays tribute to all the changes made by the B&W R&D team. Set up in PM‘s listening room powered by the mighty 350W Classé Delta pre/power amps [HFN Jun ’21], with the Melco N1ZS20 music library [HFN Jun ’17], the speakers proved that while they relish a good clean dose of power, when so driven they are capable of astounding results.

Indeed, having positioned the speakers in what was the long-established optimal position for the resident 800 D3s, we later pulled them out a little further from the walls – easy, with that new wheel arrangement – so mighty was the bass on offer here from the Classé/B&W combination. While that didn’t alter the weight of low-end available, which is consistently phenomenal, it did tighten things a smidge, making even more of the speaker’s excellent low-end definition.

Also worth noting is that the magnetically-attached grilles provided for the bass and midrange units have less impact on the sound than any we have encountered, but have a twist – quite literally. When attaching them, it’s necessary to rotate them to align the magnets, as otherwise they will fall off… So, it’s a matter of offering them up, then rotating them slightly until the magnets abruptly ‘grab’.

With the studio heritage of the 801 series – the original was swiftly adopted as a reference by Abbey Road – it seemed only fitting to commence auditioning with some classical music, in the form of the remarkable Octave Records two-volume set of Zuill Bailey playing the Bach solo cello suites [Octave OCT-0008; DSD64]. Instantly there was a marvellous sense of three-dimensionality, of the instrument in space. I was tempted to push up the level a little – the 801 D4s will take a lot of power, and play extremely loud with no stress – whereupon the presentation became even more ‘real’, from the sound of bow on string and the resonance of the body of the instrument plus, of course, the acoustic around it.

The superb recording was conveyed with remarkable presence and detail – but all to the benefit of the music, not as a distraction. These are not in any way speakers lending themselves to a quick listen: the 801 D4s draw you into the music, and just won’t let go, so compelling is their presentation.

Thrilling Impact

A familiar test-track – the Jerry Junkin/Dallas Winds recording of the John Williams march from 1941 [At The Movies; Reference Recordings RR-142, DSD64] – thrilled from the off, with the distant percussion under the opening phrases in the woodwind resolved wonderfully. And when the bass drum kicks in, it does so with both serious conviction and absolute speed, the snap of snare-drums and the crispness of the tuned percussion set against the impact of the low bass, and the wide-open dynamics as the track builds piling on the excitement.

That mixture of growling low frequencies and absolute detail also serves well ‘The Haunted Ocean’ from Max Richter’s Exiles [DG 00289 486 0445], the bass truly menacing and fully energising the room without ever seeming overblown or excessive, and still leaving plenty of space for the finely-detailed instrumentation above it.

Loading up Patricia Barber’s latest album, Clique [Impex IMP7002; DXD], the entrance of her voice on ‘Shall We Dance?’ is astonishing in the intimacy of its focus – it just hangs in the room between the speakers, with the accompanying bass, brushed drums and piano delicious in their clarity. The warmth of the ambience is lovely, as is the way Jim Gailloreto’s sax solo soars out of the mix, precisely located and with wonderful breathy reediness and the sense of the keys working.

Also sparkling in its intimacy is Anna Fedorova’s new release, Shaping Chopin [Channel Classics CCS 43621; DSD128], her reading of the Three Mazurkas, Op.50, treated to that full picture of the scale and size of the piano. Every note, every touch is wonderfully clear, and there’s such a persuasive impression of the instrument in the room, with the expression of the playing beautifully resolved.

Switching to the lush sound of Charlie Watts Meets The Danish Radio Big Band [Impulse! 0602557441932], the take on ‘Paint In Black’ has real depth to the sound of the massed forces. Here the solo guitar has great character, but above all Charlie Watts drives it with such restrained drumming, always leading the rhythms rather than simply cruising at the back. It’s an understated, beautifully crafted track, and hugely impressive through these ultra-revealing speakers, with their controlled, tightly-resolved soundstaging and superb bite when required. When Charlie gets into an easy groove with ‘You Can’t Always Get What You Want’, the speed of the big 801 D4s is much in evidence: the drumming is so laid-back, but so tight.

Serious Slam

By contrast, the big slam of the opening of Yes’s ‘Yours Is No Disgrace’ [The Yes Album; Atlantic WPCR 15903, DSD64] just cannons out from the speakers. The complex keyboards and driving, grumbling bass line fuse with the drums to drive the track relentlessly, and those harmonies are wide-open, as are the words – for good or bad! Yes, the soundscape is huge here, and the low end from those two aerofoil drivers is both punchy and remarkably controlled. These speakers will also go scarily loud with enough amplification driving them, but they remain resolutely clean and clear – a fitting apex to B&W’s latest 800 Series Diamonds.

Hi-Fi News Verdict

Not a match for low-powered tube amps, but driven firmly the new B&W flagships are capable of a sound as informative as it is vivid. They bring to life everything from driving rock to the most subtle of solo instruments and voices, with breathtaking insight into performance and music alike. Yes, they’re demanding of both amplifier and system quality, but get it right and they will thrill and entice like almost no other.

![Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4 [Piano Black]](https://audioexchange.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Bowers-Wilkins-801D4-front.jpg)

![Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4 [Piano Black] - Image 2](https://audioexchange.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Bowers-Wilkins-801D4-a9.webp)

![Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4 [Piano Black] - Image 3](https://audioexchange.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Bowers-Wilkins-801D4-a8.jpg)

![Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4 [Piano Black] - Image 5](https://audioexchange.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Bowers-Wilkins-801D4-fr.jpg)

![Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4 [Piano Black] - Image 6](https://audioexchange.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Bowers-Wilkins-801D4-a7.webp)

![Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4 [Piano Black] - Image 7](https://audioexchange.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Bowers-Wilkins-801D4-a5.jpg)

![Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4 [Piano Black] - Image 8](https://audioexchange.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Bowers-Wilkins-801D4-a4.jpg)

![Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4 [Piano Black] - Image 9](https://audioexchange.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Bowers-Wilkins-801D4-a3.webp)

![Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4 [Piano Black] - Image 10](https://audioexchange.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Bowers-Wilkins-801D4-a2.webp)

![Bowers & Wilkins 801 D4 [Piano Black] - Image 11](https://audioexchange.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Bowers-Wilkins-801D4-a1.webp)