dCS Bartok DAC

R380,000.00 Original price was: R380,000.00.R220,000.00Current price is: R220,000.00.

Some Specifications to highlight:

- Ethernet and USB inputs: up to 24/384 PCM, up to DSD128 (DoP)

- 2x AES/EBU and S/PDIF (coax, BNC) inputs: up to 24/192 PCM, up to DSD64 (DoP)

- Dual AES/EBU mode (for dCS components): up to 24/384 PCM, up to DSD128 (DoP or dCS-encrypted DSD)

- S/PDIF (Toslink) inputs: up to 24/192 PCM

- 2x word clock inputs, 1x word clock output (BNC)

- DXD or DSD upsampling, choice of 6 PCM filters and 4 DSD filters

- MQA support:

- Full decoding and rendering on USB and Ethernet inputs

- Rendering only on other inputs

- Single-ended RCA and balanced XLR analog outputs

- Full-resolution volume control, outputs can drive power amplifiers directly

- Headphone amp

- Balanced 4-pin XLR and single-ended 6.3mm outputs

- 1.4W RMS into 33Ω, 0.15W RMS into 300Ω at the single ended (SE) output

- Balanced output is 4x power output of SE

- Output impedance (balanced output): 0.1Ω

- Configurable output levels for full-scale input:

- 0.2, 0.6, 2 or 6V RMS on analog outputs

- 0, -10, -20, -30dB on headphone outputs

- Control either via front touch panel, or a Mosaic control app on iOS and Android

Description

Herb Reichert auditioned the dCS Bartók in June 2021 (Vol.44 No.6):

I finally get what those unboxing videos are all about.

As I deciphered my way through the dCS Bartók’s triple boxes (footnote 1), my sense of audiophile entitlement rose as I opened each successive box. Inside the last box, the Bartók was wrapped in a black velvet drawstring pouch. That made me smile until I realized that the Bartók was so big that I had nowhere to put it. It requires a shelf at least 19″ deep that can support 36.8lb. My desktop system shelf is only 16″ from its front edge to the wall; previously, the biggest DAC/headphone amp I’ve installed there was the Mytek Manhattan II, which only needed 14″ front-to-rear (including space for cables) and only weighed 16lb.

On my desk, the dCS Bartók usurped 323 square inches (17″ × 19″ with cables connected). Which suggested to me that it was intended to be installed not on a desk or shelf but on a fancy equipment rack.

When I moved the Bartók to my not-so-fancy equipment rack, I discovered it provides no line-level inputs. Therefore, even though the Bartók includes the optional headphone amplifier, I’d need a second headphone amp to listen to LPs via headphones.

As I double-checked the innermost box, I realized the Bartók has a front-mounted volume control, but a remote control is not included (footnote 2). Apparently, dCS intended the Bartók to be used via Ethernet with their own Mosaic Control app. Which is mostly what I did.

Listening with loudspeakers

When the Bartók arrived, I was setting up my floor system so that I could roll some tubes for last month’s Gramophone Dreams. After installing the Zu Audio Soul Supreme loudspeakers, I played Benoît Menut: Les Éles (24/96 FLAC Harmonia Mundi/Qobuz) performed by cellist Emmanuelle Bertrand. As I listened, I kept thinking that I’ve underestimated these Soul Supremes. They’re much more resolving than I’ve told my readers. Maybe it’s the amp? Or the Triode Wire Labs American Series speaker cable? I wondered.

Right then, powered by Ampsandsound’s Bigger Ben headphone and speaker amplifier, the Soul Supremes sounded like Quad ESL-57s with cojones.

I had never before experienced so much natural-sounding micro-micro information. That new nanodata just rippled and sparkled as it charged the air between and behind the Zu speakers. I had never experienced this kind of electrostat-like definition from the always-fast but slightly grainy (and occasionally gruff) Soul Supremes. It was disturbing.

What I was experiencing was the dCS Bartók DAC forcing the Zu speakers to sound more dynamic, detailed, and scintillating than I ever heard them sound with the HoloAudio, in ways I never expected to hear from digital. It was a very exciting audio moment, and I had not done anything: no setup, or filter choices, no manual reading, nothing—except plug the Bartók into the system and listen casually.

Filters: Exploring the Bartók’s filters was slightly daunting. Usually, I pride myself on being able to distinguish the sound character of digital reconstruction filters; typically I end up preferring one or another type of linear phase, slow rolloff.

With the Bartók, I struggled to grasp filter-to-filter differences. Its filters did not fall into any of my preconceived sonic types. After a couple of days experimenting (and asking friends what they use), I settled on the short, linear-phase Filter 3, mainly because I liked its bite and contrast structure. It struck a nice balance between hard and soft, played the whole piano note, and kept the music taut and lively.

Via USB: The dCS Bartók is the first DAC I’ve used in my studio with an Ethernet port, which I was excited to try, but I thought I should begin by comparing the Bartók to my reference HoloAudio May (Level 3) via USB, using the same AudioQuest Cinnamon cable connected to my Mac mini.

Playing my new favorite Charles Mingus recording, The Complete 1960 Nat Hentoff Sessions (16/44.1 FLAC Essential Jazz Classics/Tidal), both DACs showed me how clear and descriptive and solidly there this recording presents Mingus and his band. Both DACs delivered the fun and excitement of that thereness. But! The dCS Bartók took the excitement factor to a higher, more explicit level.

My only complaint with the HoloAudio May, which always seems completely insightful, exceedingly undigital, and extraordinarily neutral of tone, is that it can sound too matter-of-fact and maybe a little shy on vivo. I’ve noticed a similar just-the-facts manner with other, more expensive, R-2R DACs, so I presumed those qualities are a byproduct of the May’s R-2R architecture.

The much more expensive dCS Bartók sounded as undigital and steady-handed as the May but delivered recordings with a more titillating vividosity that I found extremely appealing. It took recordings like this Mingus, which I already thought were superinvolving, and opened them up further, making them sparkle and dance in a way that didn’t happen with the May.

Via Ethernet: Mosaic Control is the name of dCS’s iOS and Android app for music streaming and device management. Downloading it from the Apple App Store allowed me to upgrade the Bartók to the latest firmware and (finally) experience streaming without my draught horse computer in the source chain. Everyone always told me that bypassing my computer would get rid of grunge and noise, but I never imagined how much new clarity I would experience. My Bartók listening via Ethernet forced me to admit that I’ve been a fool to hang on to my computer this long. (Too soon old, too late schmart.) Now it is forcing me to employ audio journalism’s No.1 cliché: Many veils were lifted! Without the computer, recordings felt more alive, naked, and pure. Tidal seemed fresher and Qobuz seemed more hi-rez.

Also, with the Bartók via Ethernet, Tidal Masters (MQA) delivered more of its storied lucidity, tonal correctness, and spatial acuity than it does with the Mytek Manhattan II DAC (via USB). Also, playing Bill Frisell, Dave Holland, and Elvin Jones (24/44.1 MQA Nonesuch/Tidal), I noticed a distinctly improved sense of beat-and-rhythm-keeping, which I also noticed with the Bartók’s other MQA renderings. In my studio, the Bartók made MQA new again.

Listening with headphones

The dCS headphone amp is specified to put 1.4W into 33 ohms and 0.15W into 300 ohms. Output levels of full-scale, –10dB, –20dB, or –30dB may be selected in the menu.

As always, I began my headphone amplifier auditions with the super-resolving, low-sensitivity (83dB/mW), 60 ohm, HiFiMan Susvara open-backs ($5000). If the Bartók drives the Susvara’s gold-sputtered nano-thin planar-magnetic diaphragms, it will probably drive the rest of my headphone herd.

The main reason I use high-resolution headphones like the Susvara is that they enable me to better “peer into” recordings like Cabaret Modern: A Night at the Magic Mirror Tent (16/44.1 FLAC Winter & Winter/Tidal). This album is a surrealistic sound collage that attempts (ironically) to mimic a live cabaret experience. Superficially, it is a homage to the famous 1966 John Kander and Fred Ebb musical Cabaret. It is very cinematic in its you-are-inside-the-tent effects. With the Bartók translating Cabaret Modern through the Susvara, the sound was squeaky-glass clean and direct. I felt more connected than ever to Nöel Akchoté and his band of artist-performers. The Bartók DAC made the collaged effects of MC chatter, singing, applause, and audience mumblings almost humorously obvious. Voices were so crisply rendered that syntax and semantics were exposed equally—in a way that made the words extra-humorous and extra–tongue-in-cheek.

Now, if I were asked by a bloke on the street what headphones to use with their new Bartók, I would likely recommend Focal’s dynamic Stellia closed-backs ($2995). They have an impedance rating of 35 ohms, and their 106dB/mW sensitivity makes them a cinch to drive. The Stellia’s pure beryllium domes transcribe almost as much data as the Susvara. Their cognac-and-mocha styling makes them a perfect luxury-styled accessary to the Bartók’s sleek design. Besides their powerful, extra-tight closed-back bass, the Stellia’s chief sonic virtue is the vibrant intensity with which it portrays tonal gradations in the midrange. This makes them perfect for my latest obsession: 1952 Columbia recordings of the Budapest String Quartet performing Beethoven quartets.

With the Stellia, Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge in B-Flat Major, Op.133 (24/192 FLAC Columbia/Qobuz) was relaxed, detailed, and authoritative, but maybe a little astringent through the upper octaves. Sometimes with the Bartók (and Filter 3), the Stellia’s beryllium dome got a little metallic-sounding. This never happened with the HoloAudio May or Mytek Manhattan II DACs, but then neither of those DACs played Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge as vigorously or high-rez vividly as the dCS Bartók. To my ears and taste, the Bartók and Stellia made an attractive, lucid, and musically rousing partnering; one I could live with forever.

dCS crossfeed: I’ve never understood the attraction of crossfeed. As I said, I use headphones to excavate the smallest hidden sounds buried in a recording—especially the reverberation and 3D volumes of room air. I’m not looking for remixing or remastering—just the clearest possible view. But the dCS Bartók includes a crossfeed feature, so I felt obliged to try it, just in case it did something really special.

The stated purpose of crossfeed is to reduce those distracting right-left stereo effects that are unavoidably exacerbated by headphones. The first overtly right-left album I could think of was Sonny Rollins’s Way Out West (24/192 FLAC Contemporary/ Qobuz), so I tried it.

When I first engaged the Bartók’s crossfeed (via the Mosaic app), the effect was pleasant enough but dulling, undermining engagement. Then I noticed what appeared to be two additional crossfeed options: Expanse 1 and 2. Hmmm? Expanse 1 seemed to restore musical energy lost with the simple crossfeed while simultaneously moving Sonny’s sax to a center position, outside my head. Expanse 2 seemed to further enhance energy and three-dimensionality. Further comparisons with the original recording indicated these “expansions” involved a much more complex processing than a simple crossfeeding of stereo information.

Curious about what was happening, I discovered a white paper that explains dCS’s apparently unique approach.

The problem crossfeed aims to address is that with loudspeakers, the left ear receives information from the right speaker, and vice versa, at lower amplitude and with a slight delay. With headphones, there’s much less of this. The cheap-and-dirty solution is to feed a fraction of the left-speaker signal to the right ear, and vice versa. That approach has some disadvantages, though—not least the fact that much natural reverberation information is contained in the difference signal between the two channels, so the crossfed signal cancels some of it out. Another complication is that different headphones are tuned differently and that everyone’s head is different—so in principle, crossfeed should be optimized for every headphone and each person’s individual head. That’s not practical.

The white paper explains the dCS approach, incorporated in the two Expanse options—how the incoming signal is equalized and preprocessed in the digital domain. Height and width information are enhanced, extending soundstage width and stabilizing reverberation content. Then, in the crossfeed stage, the signal is delayed to simulate left signals being heard by the right ear and vice versa. The delay and frequency profile of the crossfed signal is based on some “large corpus” (dCS’s term) of head-related transfer functions—an average head, you might say—so that dCS’s version of crossfeed doesn’t work better for some people than for others.

I asked dCS’s John Quick what the difference was between Expanse 1 and Expanse 2. “The difference between the two Expanse modes comes down to the amount of recovered reverberant information the Expanse DSP delivers,” he replied. “We provide this to allow listeners to decide for themselves what balance of instrumental timbre versus acoustic spaciousness suits them best.”

So, dCS did concoct something special. Something I might approve of. Compared to the uncrossfed 24/192 Way Out West, Expanse 1 and 2 improved the punch, presence, clarity, and impact of this album.

Of the three crossfeed options—simple crossfeed and the two Expanse modes—I ended up preferring the Expanse 2 option, although ultimately I prefer the uncrossfed sound of the Way Out West LP, simply traced by my Koetsu phono cartridge.

vs Feliks Euforia: I was curious to see how the Bartók headphone amplifier would handle powering the 300 ohm, 97dB/mW ZMF Vérité closed-backs and how it would compare to the $2599 Feliks Audio Euforia headphone amplifier. The tubed Euforia has no output transformer, so the sound is lively, direct, and unmolested. I expected the sparkling vitality of the dCS DAC to complement the shimmering triode-tubeness of the Euforia, and it did. The dCS DAC made the Feliks amp sound more awake and vital than it ever did with the HoloAudio May or the Mytek HiFi Manhattan II.

The Bartók’s headphone amp delivered a classic, clean, solid state sound, which in comparison made the Euforia sound a little dawn-in-the-forest misty.

My alien abduction

Less than 1% of my music is stored in files on hard drives. Despite people’s urging, I have felt no pressing need to add a streamer or control app (like Roon) to my listening lifestyle. When I use Tidal or Qobuz, I’ve simply used their streaming apps, running them on my computer.

Obviously, and unfortunately, I did not grasp how my computer was indeed a sonic ashtray, and that giving it up would make the air in my music that much fresher. Likewise, I never imagined how a simple Ethernet cable and streaming control app could force me to reconsider what digital transparency sounds like.

At Munich High End in 2019, I kept grinning and effusively praising the Bartók when I auditioned it via its headphone amp. Therefore, I was not surprised at how easily and musically it handled every headphone I tried.

But the wonderment that overshadowed everything was: The DAC inside the Bartók hit my listening life like a UFO landing in my room. Its vibrant effect on familiar recordings was nothing short of spectacular. I am not exaggerating when I say that no digital component has raised the level of my listening pleasure as much as the dCS Bartók.—Herb Reichert

dCS Bartók 2.0 DAC Review

David Price auditions the latest version of this top-selling high-end DAC, complete with an important new firmware upgrade…

David Price auditions the latest version of this top-selling high-end DAC, complete with an important new firmware upgrade…

dCS

Bartók 2.0 DAC

£15,750 RRP (standard)/ £17,750 RRP (headphone version)

Does dCS need any introduction? After all, the Huntingdon-based company has arguably done more for top-tier high-resolution digital audio playback than any other – starting in the nineteen nineties when it made a consumer version of its studio digital convertor. The remarkable thing about 1993’s pro audio 950 – and the consumer Elgar that sprang from it in 1996 – was that rather than buying in Philips Bitstream DACs and digital filter chips like every other manufacturer at that time, dCS made its own hardware and software.

This had two obvious benefits. First, providing the boffins at dCS knew what they were doing – and as history records, they did – they could make a better sounding digital conversion ‘engine’ than Philips, Sony, et al., who had different commercial priorities that were suited to mass low-cost manufacturing. Second, as the dCS platform used a Field Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) and custom-written software code, it could be updated as and when the engineers improved it – just like we regularly upgrade the firmware in our smart devices now. It doesn’t sound so impressive in 2022, but it was practically the stuff of science fiction in the early nineties…

The result was the Ring DAC, which is so-called because of the way it does the digital number crunching; it was and is designed to minimise errors arising from hardware inconsistencies. Turning digital ones and zeros into an analogue waveform is an inherently noisy process, throwing up digital artefacts which manifest themselves as audible distortion. The dCS system was configured to minimise this phenomenon, and also to correlate it with the music signal as much as possible, so it is less audible to the human ear.

What followed the original Elgar was nearly thirty years of ever-improving dCS DACs, all featuring incrementally better versions of the Ring DAC hardware and software package. Not only this, but new functionality was added that seems totally mundane now, but at the time, in many cases, it was a world first. For example, back in the mid-nineties, there was no other way of hearing digital audio in any higher resolution than the (then) state-of-the-art DAT format (running at 16-bit, 48kHz), until dCS upgraded its pro DAC offering. Along came the potential for 24/192 PCM, and suddenly music fans – admittedly well-heeled ones – could experience hi-res digital. Those early demonstrations at hi-fi shows were practically religious experiences for some!

Not happy to rest on its laurels, the company introduced one innovation after another. Asynchronous USB audio playback was one such example, appearing first on the Scarlatti Upsampler in 2008 and then on the Debussy DAC the year after. It’s now totally standard and unexciting but a revelation to those wishing to unlock their hi-res music files stored on their computers fifteen or more years ago. Ditto streaming; dCS wasn’t quite the first to market but arguably did it better than anyone else – and was very quick to integrate this functionality into all its DACs via apps. The modern paradigm of a USB-capable, streaming DAC preamplifier – which is pretty much ubiquitous now – is arguably created by dCS.

BARTOK TIME

In 2019, dCS introduced the new Bartók. For the first time for a dCS DAC, it added optional headphone amplifier functionality, reflecting the huge explosion in the head-fi scene back then. But no less important was its full-spectrum abilities – here was a superb quality, affordable (by high-end standards) digital source component that played a vast array of digital sources and digital audio formats, and bundled proper hi-res streaming functionality via a sophisticated app. Again, it sounds nothing to write home about now, but four or so years ago, it was the shape of things to come.

Having used its predecessor, the Debussy, as my high-end reference for a good many years, I was naturally keen to hear the Bartók – and it was a considerable sonic improvement, as well as being far easier to use and more versatile. And now, sure enough, the Bartók 2.0 is here – offering a long list of interesting and useful tweaks that really move things along. The first version went on to become the company’s best-selling product, so no pressure then…

As before, it combines a network streamer, DAC, upsampler and preamplifier, plus an optional headphone amplifier, in a single chassis. The price went up a bit, adding up to £15,750 in the basic version and £17,750 with its built-in headphone amplifier. For most of us, this makes it so expensive that it’s totally out of reach, but don’t forget that dCS sells no-compromise, cost-no-object products. It’s way cheaper, for example than the company’s top Vivaldi Apex DAC at £34,650, not to mention its additional matching clock, network streamer/upsampler and transport. In effect, Bartók 2.0 is the company’s entry-level, ‘value for money’ one-box choice.

To justify the extra expense, dCS has added quite a lot – along with a ‘2.0’ suffix to remind everyone how far it has come. James Cook from dCS tells me that Bartòk 2.0 “is primarily a performance upgrade… In this area of its firmware, it is essentially identical to the Rossini, and very similar to Vivaldi. The resulting improvements in Bartòk’s musical performance moves it closer to its bigger siblings, but the more expensive and more electronically ambitious Rossini and Vivaldi remain significant upgrades.”

The mapping algorithm that controls the Ring DAC has been upgraded, which in effect, means the way in which data is presented to the Ring DAC core has been improved. “Better maths to further improve linearity and reduce distortion”, says James. Its upsampling functionality is also now said to be better, and new filter options have arrived. He adds: “While all dCS products share many similarities in terms of hardware, the software running on each unit is bespoke to that model. Designing and implementing the 2.0 mappers for Bartók represents a significant investment in terms of engineering resource.”

Three mapper settings are now available, selectable in the unit’s menu or via the Mosaic app. MAP 1 is the new default mapper, which drives the Ring DAC core at either 5.644 or 6.14MHz. MAP 2 is the original mapper which works at either 2.822 or 3.07MHz, and MAP 3 is an alternative to MAP1 that works at the same frequencies. DSD128 (DSD X2) upsampling is now available, where a DSD x2 upsampling stage is inserted towards the end of the PCM oversampling sequence, before conversion to analogue, dCS says. Also, a DSD Filter 5 setting has been added, which is said to have a relaxed roll-off with a smoother phase response which helps to remove out-of-band noise. The 2.0 software update is initiated either from the dCS Mosaic app, or via the web interface (put the IP address of the Bartók into a web browser on the same network), and takes around ten minutes to complete.

IN DEPTH

Bartók is the least fancy-looking of the company’s DAC products, lacking the expensively sculpted fascia of the pricier Rossini and Vivaldi. Yet it still presents as an extremely luxurious piece of hi-fi equipment that’s swish enough to make your friends jealous. Like the higher-end models, it sports a rotary volume control with a lovely, smooth action – working in conjunction with a pin-sharp OLED display. This is set into an exquisite aluminium fascia and casework, which really looks and feels the part.

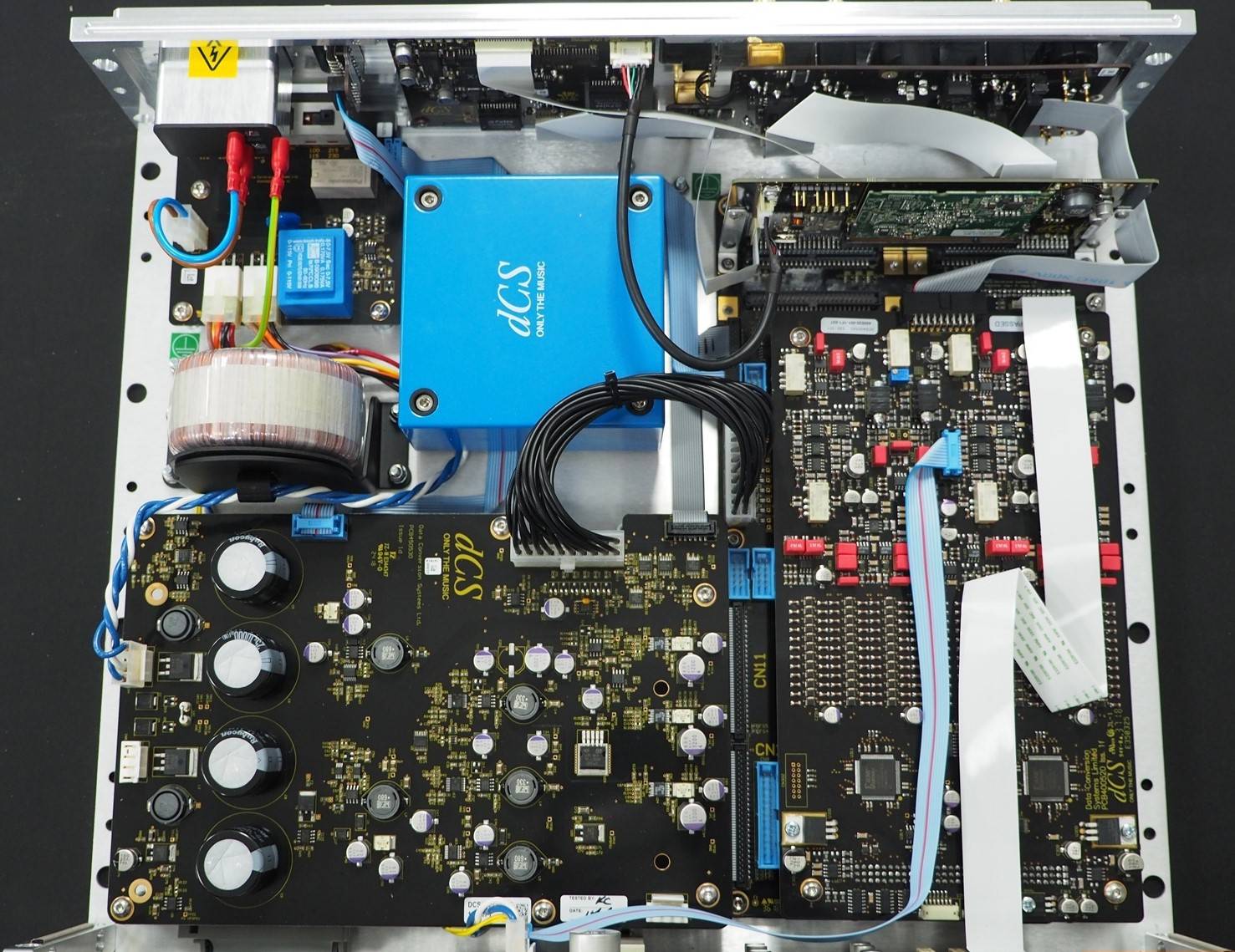

At the time of its launch, dCS Managing Director David Steven told me that Bartók took two years to develop – and is basically a stripped-down version of the higher-end designs, with the internals repurposed for the more compact case. It sports the excellent network card from Rossini, which is one of the finest streaming sources I’ve yet heard. It was specially developed together with Stream Unlimited, rather than just using a simple bought-in solution. Bartók sports the latest Rossini-generation Ring DAC processing board, although it has one less power supply. “We threw everything we had at it, plus the option of a best-in-class headphone stage too”, David told me a few years back.

Bartók plays streaming services like Spotify and TIDAL, and has dCS’s very own custom implementation of MQA, rather than using bought-in chips. Once again, like fine suits, shoes and expensive automobiles, high-end means bespoke! The unit will also play a wide range of file formats including PCM and DSD, and play out music from a NAS drive. Digital inputs include asynchronous USB, AES and S/PDIF. These are all configured via the menu button, which lets you do a not inconsiderable number of things – including changing the analogue output level voltage, swapping absolute phase, selecting the digital filter profiles for PCM and DSD, and switching on crossfeed when in headphone mode if you have the cans-friendly model.

Set-up is pretty straightforward, and the excellent Mosaic app helps with streaming settings. The crisp OLED display really elevates the user experience, telling you the sampling frequency and digital word length of what you’re playing, as well as digital source selected, etc. The company says that great care has been taken to minimise jitter at all stages via the dCS ‘auto clocking’ architecture. Network streaming currently runs at up to 24-bit, 384kHz and DSD128, supporting all major lossless codecs, plus DSD in DoP format and native DSD. As ever, the dCS volume control – shared with its more expensive siblings – is an absolute joy to use and makes using Bartók as a preamplifier, a pleasure.

This streaming DAC preamplifier has so many features and configurations that I could write an additional article detailing them. It’s an enormously versatile product, and even in this extended review, we just don’t have the space to cover everything. Instead, I’ve decided to zoom in on the key difference between this 2.0 version and the original – its new mapper. So for more in-depth information about the Bartók’s general functionality, please refer to StereoNET’s review of the original here. The only difference between the original and the new 2.0 is the software, so the hardware remains the same.

THE LISTENING

The original Bartók was a really strong performer. I think it was as good, if not better than anything I have heard at or near the price. For me, the only other rival was the Chord Electronics Dave, which was pretty much the same cost at the time of the former’s launch. The sonic difference between the two was akin to comparing coffee against tea – in other words, they’re both excellent, but it depends on your palette. With the launch of the Bartók 2.0, we see the dCS contender getting considerably more expensive but noticeably better sounding. The new mapper brings an unexpectedly large sonic improvement, and removes any criticisms of the previous version I had, at a stroke. I was genuinely surprised by the gains brought, as I toggled between mappers.

Let’s start with the basics. The Bartók running its old mapper has a very highly resolved, spacious and defined sound – one that’s quite a revelation compared to DACs around the $10,000 or more mark, for example. Like its more expensive siblings, it opens up a digital audio file and unpacks it in front of your very ears, before you. This is quite a thing to hear, even on the most mundane of CDs, for example, but one just cannot get such insight from mainstream DACs, streamers or CD players. By comparison, many of the latter sound processed and mechanical, and often cloudy and crude too.

Take I Can’t Go for That by Hall and Oates, for example. No one would ever claim this to be an audiophile recording, but that’s often the best test of a DAC’s mettle. It’s a compressed, opaque-sounding analogue affair, done in the early nineteen eighties. The Bartók on Map 2 (the old one) sounded fun; the acoustic was big, solid and physical, with a strong, driving bass and a solid snare sound. Yet I still couldn’t help myself focusing on the limitations of the recording; vocals sounded a little nasal, and slightly two-dimensional, being pushed right up forward. The production effects were fun, but again seem to shoot out of nowhere and disappear just as fast.

Move to the new Map, and whoah, what a difference! This apparently poor pop recording was unleashed with greater clarity, depth and dimensionality. Things seemed better layered, with the backing synth glide more easily discernible yet set further back in the soundstage. Backing vocals seemed less squashed now, more independent of the rest of the mix, and the lead vocals took on a more agreeable texture, with more space to them, and a fractionally less grainy feel. I was struck by the air around the saxophone on its opening and mid song solos, and the drums seemed to have a more believable texture.

It wasn’t just dimensionality that took a noticeable leap forward, because the general fun factor of the song improved too. I found myself relaxing into the music more, rather than having it machine-gunned at me in a viscerally impressive but not particularly soulful way. One obvious upgrade was the bass, which remained very strong but acquired extra bounce. Alongside this was the rhythm guitar playing, which suddenly became a thing – it seemed to syncopate better with the timing of the lead vocal line, giving the impression of everyone being in perfect sync with one another. Overall then, the song wasn’t as rigid or mechanical sounding on (the new) Map 1, and this made for a surprisingly engrossing listen.

This wasn’t just about saving the reputation of an old US pop hit, as I heard similar things with 4hero’s Another Day – which is a great recording from the early new millennium. Playing its old Map, the Bartók still showed this to have a big, spacious, widescreen soundstage and a lovely fat, rolling bassline; factor in soaring strings and a rich brass sound, and there’s much to like about this soul/rap/funk crossover classic. Indeed, I think anyone would have been impressed, both with the recording quality and the final sound out of the Magico A1 loudspeakers I was using. It certainly gave a wake-up call to the Krell K-300i integrated amplifier that was supplying the power!

Yet, if you listened really hard with a critical ear, there was a slight sense that all the instruments in the recording were pushed just a little upfront; it sounded compressed in the sense that everything was loud and in my face. It also seemed a wee bit processed, which is odd considering that it has a lot of acoustic musical instruments and was obviously recorded to a very high standard. By this, I mean that the Bartók was working great on a hi-fi level, but not so well on a musical one…

dCS Headquarters Listening Room, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom

dCS Headquarters Listening Room, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom

Again, switching to the new Map(per) was a revelation. The first thing I noticed was the improvement in stage depth and space to the recorded acoustic. And the second, which was no less profound, was a new-found urgency to vocal phrasing. Indeed the whole song seemed to mesh better and flow more freely; the lead voice was now a percussion instrument in its own right, and I loved how its phrasing gave a lilting, shuffling quality to the song. Better still, it gained a lovely texture too, no longer sounding synthetic in any way. This all tied in with the snare drum work, which shuffled along with heady abandon, mixing with the delicate hi-hat cymbal sound.

More apparent on this track was the way the Bartók with Map 1 was unpeeling the recording before my very ears – it seemed to gain more fine detail, which in turn meant that I was better able to follow all the different strands of the mix all the way through. This made the Rhodes electric organ playing far more audible than with the old mapper, and seemed to lend backing vocals an ethereal quality that they didn’t previously possess. Last but not least, one of my favourite orchestral instruments, a cor anglais, was better audible, merrily playing away in the background.

That sense of everything being crammed in together more tightly with the original mapper carried over to the rock classic that is Subdivisions by Rush. Compared to the new one, it initially seemed to sound better – as the soundstage seemed compacted and pushed forward, making it a little more edgy and raucous. But the Magico speakers, and also my reference Yamaha NS-1000Ms, soon proved able to reveal what was really going on. Indeed, the better and more subtle your system is, the more you’ll be able to hear the new mapper in a positive way. Map 1 sounded enormously satisfying, being very detailed, textured and layered with a hear-through clarity that precious few other commercially available DACs provide.

This is a nasty track for any source, as it’s pretty compressed and very dense with a lot going on inside; through poor systems it sounds like a horrible dirge, but opens up generously on the very best ones. Here I heard the Bartók reproducing the lead synthesiser with amazing timbral accuracy, separating out all the different strands of the mix with forensic accuracy. I particularly loved the way that things came together in a highly rhythmically engaging way. Dynamics sounded super convincing too, and I could almost feel the sweat on drummer Neil Peart’s brow. Set in front of all this was a synthesiser line that was gorgeously fluid, sounding more like an expressive lead instrument than a backing. Best of all was that I found myself able to listen to this track at really high levels, but ended up with no ringing in my ears – a true sign of a really low distortion source.

THE VERDICT

No matter what music you play, at whatever resolution, regardless of source, the latest dCS Bartók 2.0 is a significant upgrade on its predecessor. Better still, owners of the original can benefit from all the improvements with a simple software upgrade – such is the company’s future-proof way of working. It’s a hugely versatile package, bringing even better sound and more facilities to an already state-of-the-art DAC. It’s not exactly cheap, but this product takes you into a rarefied world of elite digital sources with precious few compromises. Hear it if you possibly can.

Related products

-

Naim CDX2 CD Player

R130,000.00Original price was: R130,000.00.R48,000.00Current price is: R48,000.00. Add to cart -

Bow Technologies Wizard II/Walrus/Warlock/Wand

R140,000.00Original price was: R140,000.00.R62,000.00Current price is: R62,000.00. Add to cart -

Ayre Acoustics QB-9 USB SACD Decoding DAC

R90,000.00Original price was: R90,000.00.R24,000.00Current price is: R24,000.00. Add to cart -

iFi Aurora

R42,000.00Original price was: R42,000.00.R29,000.00Current price is: R29,000.00. Add to cart