EAR 890 power amplifier (Level A Upgrade R18k)

Original price was: R124,000.00.R38,000.00Current price is: R38,000.00.

I have always wanted to hear an EAR amplifier. Have chatted with many people and read quite a few reviews of their products. All of them seemed to fee that these amplifiers were excellent. Well, I had a chance to meet the big cheese, U.S. importer Dan Meinwald, at the recent CES show. Dan proudly imports England-based EAR products. I bugged Dan to review their amplifiers and he suggested one of their newer models, the 890 power amplifier. This amplifier is among EAR’s higher-powered models and produces 70 watts per channel in stereo, yet is bridgeable to 140 watts in monoblock. For your information, EAR has recently unveiled some new products that include the 890 power amplifier plus an integrated amplifier version called the 899. They are also re-introducing the “Silver Jubilee Limited Edition” EAR 509, the classic 100 watt monoblock tube power amplifier using the designer’s favorite 509/519 tube, plus a solid-state phone section called the model 324. It is said to employs circuitry similar to the Paravicini 312 Power Centre pre-amplifier. The 312 amplifier retails at an eye opening $18,000 and is available only by special order.

The Designer

By the way, Tim de Paravicini is the head designer of the EAR products (which stands for Esoteric Audio Research). Tim is a really interesting man as his accomplishments in audio are incredible. He has designed amplifiers for Lux Corporation (Luxman), Michaelson and Austin, and worked as a design consultant to Tangent Loudspeakers, Musical Fidelity and Alba Radio Corporation. He also designs and builds professional audio gear under the EAR banner. This includes modifying recording equipment, studio equipment, record cutting equipment, tape machines like his favorite (and legendary) Studer C37. In fact Tim’s recording studio work includes none other than famous musician and singer Paul McCartney!

In an interview for the former Audio magazine in January 1995, Tim is quoted as saying “I don’t have to use tubes in my designs; I only do it for marketing reasons. I’ve got an exact equivalent in solid state. I can make either type do the same job, and I have no preference. People can’t pick which is which. And electrons have no memory of where they’ve been: The end result is what counts. Most transistor-circuit architecture was different from tube-circuit architecture, and that’s what people were hearing, more than the device itself. The main advantage of tubes is that an average tube has more gain than an average transistor. Second, tubes don’t have the enormous storage times of transistors, so they are very fast. Tubes can go to 100MHz without trying.” Hmmm-very interesting. Is it possible that the typical sounds from tube and transistor gear sounds different because of the circuit topology rather than the actual device? Interesting debate, is it not?”

Tim de Paravicini is also a very controversial individual. Some people have called him (among other things) arrogant, “the wild man of audio” and “the best tube circuit designer alive”, as well as probably some less flattering names. This, writes Hi-Fi News in November 1994 “attests to both the fear he instills in his opposition and the respect which even his rivals hold for him.” I met Tim at CES a number of years ago and he struck me in our short conversation as a very confident and extremely bright man, probably bordering on genius. I have heard from several sources that he has solved circuit problems in seconds that have baffled other designers for months or more. Quite an interesting man! he is an individual and something I believe we need more of. Tim’s uniqueness is much needed instead of everyone trying to behave like the masses or like someone else.

Construction And Features

I was really impressed with the EAR 890 amplifier when first receiving it. It was double-boxed, which is a very good idea because the amplifier is very heavy and very substantially built. The chassis is very stiff and thick, providing great support for the transformers, tubes and circuitry. The tubes are held by circuit boards that are hang-fastened from the top plate. This gives the amplifier good aesthetics according to my eye as about one-quarter of the tube is below the top panel. There are two black tube cages — one for each channel to protect the tubes. These cages are fastened in a really strange way that makes them very difficult and very time consuming to remove and install. The same bolts that hang-fasten the power tubes circuit board are the ones that fasten the cages. To loosen the cages, you have to remove the bottom (yes, you read right) cover from the amplifier. Then you turn the amplifier on its side and remove the two center nuts that fasten the KT90 power tube circuit board. There is a total of six bolts holding each channels circuit board. Now you have the circuit board loose at the middle which flexes, thus allowing the removal of the bolts that screw to the tapped sheet metal of the cages. The tapped sheet metal covers are too thin to get a good grab and therefore the two center bolts appear to lack the ability to become a tight fit and thereby hold the center portion of the circuit boards. In fact one of the tapped holes was already stripped!

Okay George, all this is confusing. So what does this mean? Well, this complicated fastening system creates a few problems. It makes swapping tubes, removing and installing the tube cages a very difficult and time-consuming task. It also does not allow the center bolts holding the circuit board to achieve a tight fit because of the little thread available at the cage. Finally, there is no center support of the circuit board when the cage is off, thus the board with the tubes sags and is very bouncy. On this last point, one can find an appropriate nut to fasten the bolt to, which will solve the problem. Sadly, the cage can not be placed on a flat surface to aid in support. Surely on a product of this class there must be a better way of fastening the cage to the chassis. Perhaps this can be done by Allen bolts threaded to the top panel that will allow access to the cage and the tubes from the top without going inside the amplifier.

The eight power tubes are the relatively new KT90 manufactured by EI. Two tube amplifier designers told me that they use EI tubes in their pre-amplifiers. They agreed EI tubes are excellent and very quiet, but have low consistency, at least in pre-amplifier low signal tubes. They said one has to through about six to eight tubes to get one good one. Both also said they are the best sounding of the modern-made conventional tubes. As they say, “no pain no gain.”

The front panel is very simple and very attractive. It is made from a thick piece of metal (brass, I believe) that has been chrome-played. There is an illuminated on/off switch on the right-bottom, though the one shipped was installed crooked. An easy fix and could be attributed to possible rough shipping. The power transformer (or mains transformer for you Brits) is quite a good size, very heavy and is positioned in the middle front of the amplifier complete with chrome bell caps. The output transformers are located at the rear corners of the chassis and are also topped off with chrome bell caps. Very nice.

There is a metal cover on top of the chassis with the amplifier’s schematic printed on it. This cover screws off, allowing access to the soldered portion of the driver tube circuit board. The driver tubes face head down and are located inside the chassis. This arrangement would make it very easy to service the amplifier in allowing access to both sides of the board without removing it. it also places the smaller signal tubes [ECC85 (6AQ8) and ECC83 (12AX7)] inside the chassis facing downward. While unconventional, the net result is that the aluminum plate on the top chassis gets very hot to the touch. This may be a deliberate part of the design. I do not know for sure, but it strikes me as counterintuitive. The other disadvantage of this is it makes tube swapping or replacing more difficult. This is not the only hot area of the amplifier. The power (mains) transformer operates quite hot. I can only touch it for about a second or so before having to remove my hand. This may be a design feature as I also noted that the Art Audio’s Diavolo single-ended power amplifier does the same thing. I am not a circuit designer, just reporting the facts.

One thing that I was not pleased with was the design of the loudspeaker binding posts. They were positioned too close to the output transformers and, as a result, I could not get these knurled (round) posts tight. Because these posts did not have a six-sided design, I could not use the Postman or Audioguest wrench to tighten down the loudspeaker cables. About half of these posts also would revolve around their connection to the top chassis plate further preventing me from tightening the posts properly. The last problem with these posts is that the nuts have been tapered at the contract point. Therefore making it impossible to wrap bare wire loudspeaker cables around them. One has to place this wire through the “eyelet” hole, which crushes and shears smaller wires.

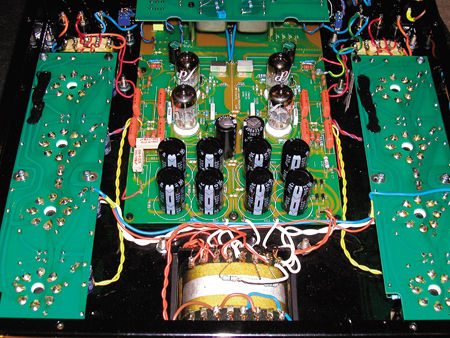

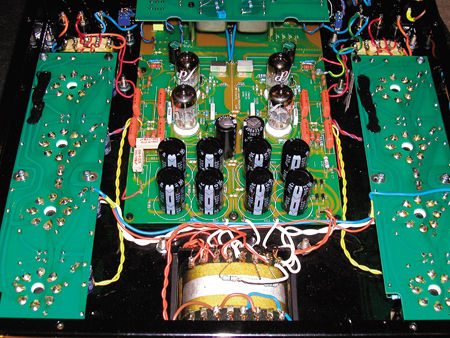

Looking at the inner construction of the mounted components and circuit boards was very interesting. One thing I was happy to see was that there was no “clip-on” connectors used anywhere. That’s great! The snap-on connectors normally used degrade the sound substantially in my experience. The AC switch also felt very lightweight and not very substantial. This is something I have noticed with many amplifiers. It makes me wonder why I put an 8-10 gauge special power cord when the electricity then goes through typically light-weight AC switches and tiny chassis wire. Again, I am no designer so perhaps this does not matter, but I have experimented with temporarily removing the AC switch and the associated thin wires in my Audio Note Meishu integrated 300B amplifier and found it made a noticeable improvement in the sound. Perhaps this is the result of rational choices due to the reasonable cost of this amplifier.

One nice feature is the design of transformer wire connections. Normally the transformer wires inside the core have “pigtails” of chassis wire that are then soldered or connected to the appropriate locations. EAR employs a termination that I have never seen before. The transformer solid wires actually come out of the core and end in solderable clips, thus allowing the designer to choose the chassis wire of his choice.

Some of the assembly work also appeared amateurish to me. Black silicone was used in various locations such as fastening the chassis wires in several locations, around the tubes near the circuit board and the back of the AC switch was covered with it. This likely does not have any sonic consequences, but feel it may have an effect on the pride of ownership considering the cost of this unit at $4,995. To add to this, I also noticed that the solder joint quality on the main circuit board did not look neat or clean. Again, this may be just a visual item but would have felt better if the amp were soldered more neatly. In the final analysis it is how the amplifier reproduces music that is most important.

How Did It Sound, George?

I may have been a little critical on the design and assembly quality of this amplifier, but when it comes to the sonics this amplifier is a winner. It was nice to have a 70 watt per channel unit available to properly drive my Green Mountain Audio Continuum 2 loudspeakers to concert levels with ease. This is what I mainly used for this review. Other loudspeakers were the Spica Angelus floor standers and a highly modified pair of Energy 22 Connoisseurs.

The first thing that I noticed with this great amplifier was how easy it was to get good sound. It was not quirky or temperamental about placement, support, rack choices, wiring etc. It was a cinch to get this unit enjoyable sounding and highly listenable. I am not saying it was insensitive to these factors, it is. As an example, you can easily hear differences by swapping cables. What I want to stress here is that this amplifier was extremely enjoyable and musical no matter what you did, within reason. Too many components, including amplifiers, are overly finicky to get sounding balanced and musical. I find this very frustrating because I am constantly on edge to change this or try that, in an effort to get the component to sound decent. Maybe this is a factor of my age (49)? I do not want to go to extreme and ridiculous measures to get a piece of gear to sound good.

When first installing the EAR 890 to my system, I had a brief listen and said, “Yeah, this sounds good.” Over the next several days I listened to it with various recordings and thoroughly enjoyed them. While listening to the music I noticed at some point that there was no apparent need to get up and change anything. I did not feel like trying this interconnect, another loudspeaker cable, putting it on cones or doing anything. Just wanted to relax on the couch and enjoy the quality of the music. This might seem like a minor point, but have learned a lot from this episode. Specifically, if a component or music system does not force you to constantly get up and change things, it naturally encourages you to enjoy the music. This tells you a tremendous amount about the quality of the component or system. It means, to me, that something is inherently right about the sound. On some level, perhaps even sub-conscious, your brain, body, heart and guts connect with the music. The emotion of the music if you will. I think this is a big deal because if you do not “enjoy the music” (nyuk, nyuk) or if you are not getting the essence, nothing else matters. Thank you EAR and Dan for the lesson.

Power wise, this unit is very potent! It sounds more powerful than the 70 watts per channel rating would indicate. It drove my loudspeakers with ease and had plenty of reserve. This included my playing of large orchestral works or rock music. Sonically, this amplifier reproduces music a bit like the classic tube sound. I said a bit, not a lot. It did not sound thick or syrupy, or have that old bloated tube sound of yesteryear. Still, it did go towards the warm, euphonic side of the medium. This amplifier would be a great match for many modern loudspeakers that tend to have a more analytical sound due to tipped-up high frequencies.

The EAR 890 is especially good at reproducing voices, particularly of the male variety. You can easily hear in Frank Sinatra’s voice his power, depth, and resonance. The almost raunchy quality that makes his voice so enjoyable. The EAR 890 also gets the mass and chestiness of a person’s voice nearly perfect. Voice actually sounds like it is coming from a human body and head instead of this ethereal voice from thin air.

The bass on this gem is a touch elevated in level, thus providing a warmer, more solid sound. Again, this would work really well with most modern loudspeakers and be an excellent match with some excellent minimonitors on the market. This healthy bottom end was also pointed out in a review of another EAR amplifier, the model 861 vacuum tube power amplifier reviewed by Dayna B. for Ultimate Audio (Winter 1999). While not a major concern, it makes bass instruments a little heavier than normal though still enjoyable. One thing I enjoyed about the EAR’s bass is that it allowed the natural resonant sounds of many bass instruments to be expressed. Many times, some amplifiers sound tight and pinchy. Akin to constipated in the bass region with their overly damped sound. I notice this with solid-state amplifiers, primarily, more so than with tubed units.

High frequencies are very well handled, being light, airy and very well extended without any harshness or stridency of any kind. Very pleasing with a smoothness that allowed me to relax and absorb the music. I noticed with this amplifier that my Green Mountain Audio three-way loudspeakers were better integrated and sounded closer to the sound of one driver. The EAR is very cohesive and exceeds at integrating the lows, mids and highs extremely well.

Detail, attack, decay and resolution were excellent. The subtleties and nuances were there, yet not thrust in your face nor disembodied from the rest of the music. If you are a detail freak, or love that “hyped-up” inner detail and resolution, you would be better served to look elsewhere. This amplifier is so smooth and stress free that at first it feels as if you are loosing detail and resolution. Then you suddenly notice a singer’s many tonal and pitch changes and realize the detail is all there. It just is presented in a smoother, more relaxed perspective.

I was also impressed with the soundscaping and imaging of this amplifier. The music was expansive with good depth, when it was recorded that way, many times going beyond the edges of the loudspeakers. The music extended far back as well as in front of the loudspeakers. The time and phase coherent Green Mountain loudspeakers are a great help here with their staggered drivers and phase-correct 6dB/oct crossover slopes.

Give Me The Bottom Line

All in all, this is a great amplifier! It is extremely easy to set up and sounds good with little or no tweaking. It is about enjoying the music and not a finicky or touchy piece of gear. It is very cohesive and the tonality is excellent and very well integrated from highs to lows. There is a slight boom in the bass that is noticeable, yet not very obtrusive and may be a benefit with most modern loudspeakers. I found it very enjoyable to have a well-rounded, fuller sound to create a proper foundation to the music.

Resolution and detail are excellent and they are presented in a relaxed, smooth manner. This EAR will not likely make “detail above all” types happy. The detail and nuances are there; they’re not thrown at you, but are, more appropriately, part of the music’s tapestry.

Sound staging and imaging are terrific. Tube amplifiers have an advantage here and the EAR 890 is no exception. The music, when thus recorded, extends beyond the edges of the loudspeakers with good depth and extension. This includes “throwing” sounds well in front of the loudspeakers and find this very engaging as one gets swept into the energy and mood of the music. True stress relief served here.

The U.S. importer, Dan Meinwald, told me that the EAR 890 is one of Tim de Paravicini’s more tube-like sounding amplifiers. Generally his designs do not sound classically tube-like. I agree with Dan, this amplifier is slightly, just slightly to the warm romantic side, yet not so much so that it impedes the music. I will really miss the great musicality and powerful presentation that this amplifier produces. Amazing considering it demands very little or no tweaking on my part. Less stress and anxiety in my life is a good thing.

Most of us have at least some taste for gear that jumps out—for audio components whose sonic and musical distinctions are easy to hear from the start. In audio, unlike in the art of music itself, there’s nothing wrong with being obvious.

Then there are such products as the grand-looking 890 amplifier ($4995) from Esoteric Audio Research, which had nothing of the obvious about it during its stay in my home. Voices didn’t pop out. Groove noise didn’t vanish. Textures were neither smoothed-over nor scuffed-up. Whites weren’t whiter and colors weren’t brighter, and I had to listen to it for weeks on end before it sank in just how beautifully well the 890 played music. That’s not so much an indictment of the amp as it is of the whole audio reviewing paradigm, which, admittedly, is more about jumping in the sack than mating for life.

The EAR 890 confounds reviewers in another way: It’s a straightforward thing, and while its design and execution are not without ingenuity, the EAR 890 lacks even such basics as hand-rolled capacitors or exotic metallurgy. Good God, this amp…has no story!

Description

The EAR 890 is, in designer Tim de Paravicini’s own words, a very conventional tube amplifier. Each channel uses its own 6AQ8 dual-triode as a differential pair, working in concert with another dual-triode, the ubiquitous 12AX7. The output section uses four tubes per channel in a parallel push-pull configuration: the relatively young KT90, which de Paravicini describes as Yugoslavia’s answer to the classic KT88. This beam tetrode, which shares some physical characteristics with the EL509 power tube used in the earliest EAR amps, is used as a tetrode, albeit not in ultralinear mode.

The payoff is a hefty, hell-raising 70Wpc, operating in pure class-A (footnote 1). Although de Paravicini says he strives for extended tube life—described for our purposes as a minimum of 10,000 hours—and thus maintains plate current within the realm of sanity, you still would not want to rest your hand on the metalwork of an EAR 890 that’s been playing music for any amount of time. As we say here in the Northeast US, “Bastid git hot, dunnit?”

Other interesting details: Hobbyists whose preamplifiers lack a balance control will be cheered by the presence of individual left and right channel-level controls, mounted on the rear panel. Nearby, a top-mounted switch allows the user to transform his or her EAR 890 into a 140Wpc monoblock; two-channel enthusiasts will then need to buy another 890, while monophiles can use a single one to intimidate the corner horn or old Quad ESL of their choice. Another switch toggles between unbalanced and balanced operation, the latter involving XLR sockets and an internal pair of custom-wound line transformers.

The 890’s output transformers are also de Paravicini’s own—he perfected the craft decades ago while working for Japan’s Luxman Corporation—and they present the user with separate taps for 8 and 16 ohm loudspeakers. And, finally, the auto-bias 890 requires little in the way of user intervention apart from working the On/Off switch, which is an orange plastic button. (But Tim: Are you sure that ivory, or perhaps even whalebone, wouldn’t sound better…?)

Notwithstanding an idiosyncratic approach to holding the tube cages in place (hard-to-reach bolts that extend into the circuit-board standoffs on each channel’s output boards), the 890’s construction is logical, robust, and beautiful. The parts count is surprisingly low—especially true of the tubeless power supply, which Tim de P describes as “a boring, conventional voltage doubler”—and the whole of the amp comprises four neat circuit boards: a small one for the balanced input trannies and associated bits; one large, central board for the driver section and power supply; and two output section boards. The smooth, heavy chassis has a finish of baked enamel, and the front of the amp is anchored with a thick brass faceplate, chrome-plated and polished to the proverbial mirror finish. Heavily chromed tranny covers with brass fixing nuts, another EAR calling card, complete the look.

Listening

At first I tried the 890 with my Lowther horns, replacing the Fi 2A3 Stereo amp I usually use. (My sample of the 890 already had several hundred hours on it, so I’m afraid I can’t speak to the issue of break-in time as it affects this particular amp.) I was extremely impressed, and although it may sound simpleminded to say so, the 890’s performance made me think of nothing so much as a Fi amp with even more headroom, and a little more drive and richness in the bass. Musically, the performance was faultless. Symphonies were appropriately forceful but never lacking in poise—and, to an equal extent, never lacking in musical flow. This was not at all the choppy, mechanical sound for which some SET devotees criticize push-pull.

But for the most part, I put all 70Wpc to work using the EAR 890 with my mildly insensitive Quad ESL-989 loudspeakers (Stereophile, November 2002 and May 2003). The combination proved to be among the most sonically faultless and musically satisfying I’ve had in my home.

In the past, I’ve used the word unspectacular in a derogatory way; this time, I mean it nicely. The EAR 890 was an unspectacular amp that gave me easy access to musically important details. When I used it to play Clarence White’s “Bury Me Beneath the Willow” (from the indispensable 33 Guitar Instrumentals CD, Sierra SZCD 26023-2), I heard clearly, for the first time, how the occasional “late” note attacks in this very early White recording weren’t mistakes at all, but rather deliberate attempts to push his cross-picking pattern off the tracks, so to speak, and to shift the upstroke—and thus the emphasis in each measure—in a way that made the tune more interesting. (Special note to guitar enthusiasts: Clarence White’s cross-picking pattern was virtually always down-down-up, down-down-up, not down-up-down, up-down-up, resulting in what I consider a more old-fashioned, mildly syncopated sound.)

The 890 also let me appreciate—if not for the first time, then certainly more easily than usual—Billie Holiday’s calm, understated delivery in the unsettling “Strange Fruit” (from the album of the same name, Commodore MVCJ 19214). I’m not sure why, but the 1930s-era recording, which merely sounds quaint through most gear, seemed “righter,” more serene, more inviting through this amp-speaker combination. Even the inevitable transfer noise, though still audible, imparted less distraction and fussiness to the listening experience.

Considering the Purcell music associated with the funeral of Queen Mary (I balk at a more specific title than that if only to avoid the ire of those who rightly observe that we don’t know for sure what was performed on that miserable day in 1695), the recording I most enjoy is the one made by John Eliot Gardiner in the late 1970s (LP, Erato STU 70911). At the end of this recording of the March, the percussionist plays a roll on a kettledrum tuned to C, the sound of which is then left to fade naturally (ie, it isn’t damped by the player). Bad amps—even enjoyable bad amps—èt this all wrong, refusing to let go of the sound and making mush of it in the process. Good amps give you a natural decay that dies away cleanly, letting you hear how the sound of a kettledrum at stage left can both splash off the assortment of brass instruments at stage right and induce them to resonate sympathetically. By this standard, the EAR 890 proved itself a very good amp indeed.

And that was just the sound; musically, the 890 made for a draining experience—but in the best possible way. The second sentence in the funeral service, “In the midst of life we are in death,” was uncommonly moving through this amp: The complex and often modern-sounding intervals carried by the four sections of the choir, in a continuous dynamic exchange with the organ, came through cleanly and clearly, leading me to wonder if the 890 produced much less than average in the way of both intermodulation and gross harmonic additives.

While on the subject of good English music, I recommend an impressive recording of John Tavener’s recent Ikon of Eros, for vocal soloists, solo violin, orchestra, and choir (CD, Reference Recordings RR-102CD). Throughout the work, violinist Jorja Fleezanis plays an almost continuous violin obbligato, which she does with remarkable consistency and sweetness of tone—and which the combination of EAR 890 amplifier and Quad ESL-989 speakers played with both convincing flow and lack of coloration. In fact, the only departure from utter timbral neutrality I thought I heard through this amp was an occasional excess of richness in the upper bass—which I noticed, for instance, in the plucked cello notes of the famous second movement of Borodin’s String Quartet 2 (LP, Decca SXL 6036, in a fine Speakers Corner reissue). But the effect was so very slight that, taken in the context of the Quads’ own slight tendency toward excess down there, and the possibilities that room reactions might produce the same thing, I hesitate to even mention it.

I don’t mean to give short shrift to the 890’s considerable output power, which is, after all, among its grandest raisons d’être. All I can say—which is considerable, I suppose—is that I never once heard the 890 get into any kind of trouble, even with the Quads in the largest of my listening rooms. This was as true of heldentenors as of Mott the Hoople.

Based on my experiences with other, earlier EAR amplifiers, I expected the 890 to excel at stereo imaging—and wasn’t in the least disappointed. Using a string quartet recording to describe a home music system’s imaging capabilities has become a bit of a cliché, so I’m a little embarrassed to still be thinking of that Borodin LP; in my defense, however, while I can’t think of a single stereo recording that really suggests the spatial qualities I hear in a live concert setting, of any type of music and from any seat, good chamber-music recordings such as the above-mentioned probably come the closest. And, yes, the EAR 890 reproduced the sense of depth and performer placement that I presume is a part of the original recording with both uncanny precision and the same sense of “rightness” with which it approached the music itself. (I could also point to how well it separated the voice sections on that Purcell LP, even going so far as to suggest some curve to the choir’s risers…)

Previous EAR experiences might also have led me to expect less than the best from the 890 in terms of rhythm and pacing; it’s been a few years since I heard it, but I remember the similarly beautiful-sounding 534 being somewhat less than jaunty with upbeat music. For whatever reason—improved damping? the essential sonic differences between EL34 and KT90 tubes?—I heard no such troubles here. In fact, when I used the EAR-Quad combination to listen to such songs as “Don’t Kill” and “A Little Concerned, That’s All,” from the great album Tough Love by Hamell on Trial (Righteous Babe RBR033-D), I had just as much fun as with our “party” rig (Naim amps driving Lowther horns—wheee!).

And the opening bars of Martin Sieghart’s altogether superior Schmidt Fourth (CD, Chesky CD143) had a rhythmic insistence I don’t get even with Lowthers (although perhaps that’s because so much of it takes place in the bass registers). And when the tempo picked up very slightly, some 12 minutes later—just before the transition to the second movement and its solo cello line—the EAR-Quad combination got the idea across effectively. All in all, there was nothing soggy or slow in the way Tim de P’s amp played rhythmically demanding music.

Finally, while most of my listening was done with my usual unbalanced interconnects (my own homemade solid-core silver), a sense of duty compelled me to try the 890 in balanced mode, too. (This despite the fact that Tim de Paravicini told me he believes “There are no sonic benefits that are peculiar to balanced [operation] that can’t be accomplished with unbalanced.” He went on to suggest that the 890 offers the choice simply to accommodate customers from a pro background, who are more comfortable working in a low-impedance connection context.) In particular, I tried a balanced cable set from DNM (see this month’s “Listening“), which is at least somewhat similar in construction and intent, if you will, to my reference.

Was there a difference? Actually, yes: While I heard no distinctions one way or the other in terms of flow or timbre or pitch or drama, I did in fact hear what I took to be a better, bigger sense of scale with the balanced cables. Sorry, Tim.

Back to where I started

As much as anyone else, I enjoy audio products whose strengths are plain and upfront and obvious—that is, as long as those strengths are the sorts of things that I care to hear. (Also as much as anyone else, I find it all too easy to fall into the trap of congratulating myself for hearing any difference at all, then buying whatever seems “freshest.” Self-control is as hard to come by at my house as at yours.) I hear obvious products all the time, and I’ve even reviewed a few for Stereophile.

But as often as that happens, I tend not to covet such products. The extra few notes of bass, the heightened sense of presence, the scary-quiet groove…they’re all nice, but after enjoying the luxury of having them in my home for 90 days out of my life, I can still do without them over the course of the days that remain.

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about the EAR 890 was that, with the exception of the Quads that I used it to drive, this was the first new audio product in a very long time that I caught myself scheming to buy.

Then again, look what we’re talking about here. A $5000 amp. Mama.

I have an idea. The EAR 890’s only significant flaw is in its engraved top plate, which is screwed to the top of that enameled chassis, and on which are inscribed the words “Technology at it’s best!” For one thing, the exclamation point is unnecessary, and its removal would lend the statement more in the way of, you’ll pardon the expression, quiet power—which I imagine would appeal to Mr. de P in any event. Second, and more critical, is the inappropriate use of an apostrophe, denoting a contraction where there is none—a common mistake, and one that I saw many of my fellow teachers make with impunity when I taught sixth grade. (I think they should have got the hot lead themselves. But it is—or should I say it’s—a sadly common thing nonetheless.) So I hereby offer my services as an English major to Tim de Paravicini, and I would gladly forgo monetary pay in favor of…oh, I don’t know, perhaps some sort of barter arrangement. I will wait to see what he offers in return. I’m not holding my breath.

An expensive amp, then, but one whose only apparent flaw is grammatical. I suppose it’s possible that the EAR 890, whose designer suggests that he could make an amplifier of precisely identical performance using transistors instead of tubes, sounds as good as it does because of its ability to step out of the way of good-sounding recordings. But if that’s so, I can’t help thinking it steps out of the way more gracefully than most.

Description

Price: $4,995, upgrades $1200!!

I have always wanted to hear an EAR amplifier. Have chatted with many people and read quite a few reviews of their products. All of them seemed to fee that these amplifiers were excellent. Well, I had a chance to meet the big cheese, U.S. importer Dan Meinwald, at the recent CES show. Dan proudly imports England-based EAR products. I bugged Dan to review their amplifiers and he suggested one of their newer models, the 890 power amplifier. This amplifier is among EAR’s higher-powered models and produces 70 watts per channel in stereo, yet is bridgeable to 140 watts in monoblock. For your information, EAR has recently unveiled some new products that include the 890 power amplifier plus an integrated amplifier version called the 899. They are also re-introducing the “Silver Jubilee Limited Edition” EAR 509, the classic 100 watt monoblock tube power amplifier using the designer’s favorite 509/519 tube, plus a solid-state phone section called the model 324. It is said to employs circuitry similar to the Paravicini 312 Power Centre pre-amplifier. The 312 amplifier retails at an eye opening $18,000 and is available only by special order.

The Designer

By the way, Tim de Paravicini is the head designer of the EAR products (which stands for Esoteric Audio Research). Tim is a really interesting man as his accomplishments in audio are incredible. He has designed amplifiers for Lux Corporation (Luxman), Michaelson and Austin, and worked as a design consultant to Tangent Loudspeakers, Musical Fidelity and Alba Radio Corporation. He also designs and builds professional audio gear under the EAR banner. This includes modifying recording equipment, studio equipment, record cutting equipment, tape machines like his favorite (and legendary) Studer C37. In fact Tim’s recording studio work includes none other than famous musician and singer Paul McCartney!

In an interview for the former Audio magazine in January 1995, Tim is quoted as saying “I don’t have to use tubes in my designs; I only do it for marketing reasons. I’ve got an exact equivalent in solid state. I can make either type do the same job, and I have no preference. People can’t pick which is which. And electrons have no memory of where they’ve been: The end result is what counts. Most transistor-circuit architecture was different from tube-circuit architecture, and that’s what people were hearing, more than the device itself. The main advantage of tubes is that an average tube has more gain than an average transistor. Second, tubes don’t have the enormous storage times of transistors, so they are very fast. Tubes can go to 100MHz without trying.” Hmmm-very interesting. Is it possible that the typical sounds from tube and transistor gear sounds different because of the circuit topology rather than the actual device? Interesting debate, is it not?”

Tim de Paravicini is also a very controversial individual. Some people have called him (among other things) arrogant, “the wild man of audio” and “the best tube circuit designer alive”, as well as probably some less flattering names. This, writes Hi-Fi News in November 1994 “attests to both the fear he instills in his opposition and the respect which even his rivals hold for him.” I met Tim at CES a number of years ago and he struck me in our short conversation as a very confident and extremely bright man, probably bordering on genius. I have heard from several sources that he has solved circuit problems in seconds that have baffled other designers for months or more. Quite an interesting man! he is an individual and something I believe we need more of. Tim’s uniqueness is much needed instead of everyone trying to behave like the masses or like someone else.

Construction And Features

I was really impressed with the EAR 890 amplifier when first receiving it. It was double-boxed, which is a very good idea because the amplifier is very heavy and very substantially built. The chassis is very stiff and thick, providing great support for the transformers, tubes and circuitry. The tubes are held by circuit boards that are hang-fastened from the top plate. This gives the amplifier good aesthetics according to my eye as about one-quarter of the tube is below the top panel. There are two black tube cages — one for each channel to protect the tubes. These cages are fastened in a really strange way that makes them very difficult and very time consuming to remove and install. The same bolts that hang-fasten the power tubes circuit board are the ones that fasten the cages. To loosen the cages, you have to remove the bottom (yes, you read right) cover from the amplifier. Then you turn the amplifier on its side and remove the two center nuts that fasten the KT90 power tube circuit board. There is a total of six bolts holding each channels circuit board. Now you have the circuit board loose at the middle which flexes, thus allowing the removal of the bolts that screw to the tapped sheet metal of the cages. The tapped sheet metal covers are too thin to get a good grab and therefore the two center bolts appear to lack the ability to become a tight fit and thereby hold the center portion of the circuit boards. In fact one of the tapped holes was already stripped!

Okay George, all this is confusing. So what does this mean? Well, this complicated fastening system creates a few problems. It makes swapping tubes, removing and installing the tube cages a very difficult and time-consuming task. It also does not allow the center bolts holding the circuit board to achieve a tight fit because of the little thread available at the cage. Finally, there is no center support of the circuit board when the cage is off, thus the board with the tubes sags and is very bouncy. On this last point, one can find an appropriate nut to fasten the bolt to, which will solve the problem. Sadly, the cage can not be placed on a flat surface to aid in support. Surely on a product of this class there must be a better way of fastening the cage to the chassis. Perhaps this can be done by Allen bolts threaded to the top panel that will allow access to the cage and the tubes from the top without going inside the amplifier.

The eight power tubes are the relatively new KT90 manufactured by EI. Two tube amplifier designers told me that they use EI tubes in their pre-amplifiers. They agreed EI tubes are excellent and very quiet, but have low consistency, at least in pre-amplifier low signal tubes. They said one has to through about six to eight tubes to get one good one. Both also said they are the best sounding of the modern-made conventional tubes. As they say, “no pain no gain.”

The front panel is very simple and very attractive. It is made from a thick piece of metal (brass, I believe) that has been chrome-played. There is an illuminated on/off switch on the right-bottom, though the one shipped was installed crooked. An easy fix and could be attributed to possible rough shipping. The power transformer (or mains transformer for you Brits) is quite a good size, very heavy and is positioned in the middle front of the amplifier complete with chrome bell caps. The output transformers are located at the rear corners of the chassis and are also topped off with chrome bell caps. Very nice.

There is a metal cover on top of the chassis with the amplifier’s schematic printed on it. This cover screws off, allowing access to the soldered portion of the driver tube circuit board. The driver tubes face head down and are located inside the chassis. This arrangement would make it very easy to service the amplifier in allowing access to both sides of the board without removing it. it also places the smaller signal tubes [ECC85 (6AQ8) and ECC83 (12AX7)] inside the chassis facing downward. While unconventional, the net result is that the aluminum plate on the top chassis gets very hot to the touch. This may be a deliberate part of the design. I do not know for sure, but it strikes me as counterintuitive. The other disadvantage of this is it makes tube swapping or replacing more difficult. This is not the only hot area of the amplifier. The power (mains) transformer operates quite hot. I can only touch it for about a second or so before having to remove my hand. This may be a design feature as I also noted that the Art Audio’s Diavolo single-ended power amplifier does the same thing. I am not a circuit designer, just reporting the facts.

One thing that I was not pleased with was the design of the loudspeaker binding posts. They were positioned too close to the output transformers and, as a result, I could not get these knurled (round) posts tight. Because these posts did not have a six-sided design, I could not use the Postman or Audioguest wrench to tighten down the loudspeaker cables. About half of these posts also would revolve around their connection to the top chassis plate further preventing me from tightening the posts properly. The last problem with these posts is that the nuts have been tapered at the contract point. Therefore making it impossible to wrap bare wire loudspeaker cables around them. One has to place this wire through the “eyelet” hole, which crushes and shears smaller wires.

Looking at the inner construction of the mounted components and circuit boards was very interesting. One thing I was happy to see was that there was no “clip-on” connectors used anywhere. That’s great! The snap-on connectors normally used degrade the sound substantially in my experience. The AC switch also felt very lightweight and not very substantial. This is something I have noticed with many amplifiers. It makes me wonder why I put an 8-10 gauge special power cord when the electricity then goes through typically light-weight AC switches and tiny chassis wire. Again, I am no designer so perhaps this does not matter, but I have experimented with temporarily removing the AC switch and the associated thin wires in my Audio Note Meishu integrated 300B amplifier and found it made a noticeable improvement in the sound. Perhaps this is the result of rational choices due to the reasonable cost of this amplifier.

One nice feature is the design of transformer wire connections. Normally the transformer wires inside the core have “pigtails” of chassis wire that are then soldered or connected to the appropriate locations. EAR employs a termination that I have never seen before. The transformer solid wires actually come out of the core and end in solderable clips, thus allowing the designer to choose the chassis wire of his choice.

Some of the assembly work also appeared amateurish to me. Black silicone was used in various locations such as fastening the chassis wires in several locations, around the tubes near the circuit board and the back of the AC switch was covered with it. This likely does not have any sonic consequences, but feel it may have an effect on the pride of ownership considering the cost of this unit at $4,995. To add to this, I also noticed that the solder joint quality on the main circuit board did not look neat or clean. Again, this may be just a visual item but would have felt better if the amp were soldered more neatly. In the final analysis it is how the amplifier reproduces music that is most important.

How Did It Sound, George?

I may have been a little critical on the design and assembly quality of this amplifier, but when it comes to the sonics this amplifier is a winner. It was nice to have a 70 watt per channel unit available to properly drive my Green Mountain Audio Continuum 2 loudspeakers to concert levels with ease. This is what I mainly used for this review. Other loudspeakers were the Spica Angelus floor standers and a highly modified pair of Energy 22 Connoisseurs.

The first thing that I noticed with this great amplifier was how easy it was to get good sound. It was not quirky or temperamental about placement, support, rack choices, wiring etc. It was a cinch to get this unit enjoyable sounding and highly listenable. I am not saying it was insensitive to these factors, it is. As an example, you can easily hear differences by swapping cables. What I want to stress here is that this amplifier was extremely enjoyable and musical no matter what you did, within reason. Too many components, including amplifiers, are overly finicky to get sounding balanced and musical. I find this very frustrating because I am constantly on edge to change this or try that, in an effort to get the component to sound decent. Maybe this is a factor of my age (49)? I do not want to go to extreme and ridiculous measures to get a piece of gear to sound good.

When first installing the EAR 890 to my system, I had a brief listen and said, “Yeah, this sounds good.” Over the next several days I listened to it with various recordings and thoroughly enjoyed them. While listening to the music I noticed at some point that there was no apparent need to get up and change anything. I did not feel like trying this interconnect, another loudspeaker cable, putting it on cones or doing anything. Just wanted to relax on the couch and enjoy the quality of the music. This might seem like a minor point, but have learned a lot from this episode. Specifically, if a component or music system does not force you to constantly get up and change things, it naturally encourages you to enjoy the music. This tells you a tremendous amount about the quality of the component or system. It means, to me, that something is inherently right about the sound. On some level, perhaps even sub-conscious, your brain, body, heart and guts connect with the music. The emotion of the music if you will. I think this is a big deal because if you do not “enjoy the music” (nyuk, nyuk) or if you are not getting the essence, nothing else matters. Thank you EAR and Dan for the lesson.

Power wise, this unit is very potent! It sounds more powerful than the 70 watts per channel rating would indicate. It drove my loudspeakers with ease and had plenty of reserve. This included my playing of large orchestral works or rock music. Sonically, this amplifier reproduces music a bit like the classic tube sound. I said a bit, not a lot. It did not sound thick or syrupy, or have that old bloated tube sound of yesteryear. Still, it did go towards the warm, euphonic side of the medium. This amplifier would be a great match for many modern loudspeakers that tend to have a more analytical sound due to tipped-up high frequencies.

The EAR 890 is especially good at reproducing voices, particularly of the male variety. You can easily hear in Frank Sinatra’s voice his power, depth, and resonance. The almost raunchy quality that makes his voice so enjoyable. The EAR 890 also gets the mass and chestiness of a person’s voice nearly perfect. Voice actually sounds like it is coming from a human body and head instead of this ethereal voice from thin air.

The bass on this gem is a touch elevated in level, thus providing a warmer, more solid sound. Again, this would work really well with most modern loudspeakers and be an excellent match with some excellent minimonitors on the market. This healthy bottom end was also pointed out in a review of another EAR amplifier, the model 861 vacuum tube power amplifier reviewed by Dayna B. for Ultimate Audio (Winter 1999). While not a major concern, it makes bass instruments a little heavier than normal though still enjoyable. One thing I enjoyed about the EAR’s bass is that it allowed the natural resonant sounds of many bass instruments to be expressed. Many times, some amplifiers sound tight and pinchy. Akin to constipated in the bass region with their overly damped sound. I notice this with solid-state amplifiers, primarily, more so than with tubed units.

High frequencies are very well handled, being light, airy and very well extended without any harshness or stridency of any kind. Very pleasing with a smoothness that allowed me to relax and absorb the music. I noticed with this amplifier that my Green Mountain Audio three-way loudspeakers were better integrated and sounded closer to the sound of one driver. The EAR is very cohesive and exceeds at integrating the lows, mids and highs extremely well.

Detail, attack, decay and resolution were excellent. The subtleties and nuances were there, yet not thrust in your face nor disembodied from the rest of the music. If you are a detail freak, or love that “hyped-up” inner detail and resolution, you would be better served to look elsewhere. This amplifier is so smooth and stress free that at first it feels as if you are loosing detail and resolution. Then you suddenly notice a singer’s many tonal and pitch changes and realize the detail is all there. It just is presented in a smoother, more relaxed perspective.

I was also impressed with the soundscaping and imaging of this amplifier. The music was expansive with good depth, when it was recorded that way, many times going beyond the edges of the loudspeakers. The music extended far back as well as in front of the loudspeakers. The time and phase coherent Green Mountain loudspeakers are a great help here with their staggered drivers and phase-correct 6dB/oct crossover slopes.

Give Me The Bottom Line

All in all, this is a great amplifier! It is extremely easy to set up and sounds good with little or no tweaking. It is about enjoying the music and not a finicky or touchy piece of gear. It is very cohesive and the tonality is excellent and very well integrated from highs to lows. There is a slight boom in the bass that is noticeable, yet not very obtrusive and may be a benefit with most modern loudspeakers. I found it very enjoyable to have a well-rounded, fuller sound to create a proper foundation to the music.

Resolution and detail are excellent and they are presented in a relaxed, smooth manner. This EAR will not likely make “detail above all” types happy. The detail and nuances are there; they’re not thrown at you, but are, more appropriately, part of the music’s tapestry.

Sound staging and imaging are terrific. Tube amplifiers have an advantage here and the EAR 890 is no exception. The music, when thus recorded, extends beyond the edges of the loudspeakers with good depth and extension. This includes “throwing” sounds well in front of the loudspeakers and find this very engaging as one gets swept into the energy and mood of the music. True stress relief served here.

The U.S. importer, Dan Meinwald, told me that the EAR 890 is one of Tim de Paravicini’s more tube-like sounding amplifiers. Generally his designs do not sound classically tube-like. I agree with Dan, this amplifier is slightly, just slightly to the warm romantic side, yet not so much so that it impedes the music. I will really miss the great musicality and powerful presentation that this amplifier produces. Amazing considering it demands very little or no tweaking on my part. Less stress and anxiety in my life is a good thing.

Most of us have at least some taste for gear that jumps out—for audio components whose sonic and musical distinctions are easy to hear from the start. In audio, unlike in the art of music itself, there’s nothing wrong with being obvious.

Then there are such products as the grand-looking 890 amplifier ($4995) from Esoteric Audio Research, which had nothing of the obvious about it during its stay in my home. Voices didn’t pop out. Groove noise didn’t vanish. Textures were neither smoothed-over nor scuffed-up. Whites weren’t whiter and colors weren’t brighter, and I had to listen to it for weeks on end before it sank in just how beautifully well the 890 played music. That’s not so much an indictment of the amp as it is of the whole audio reviewing paradigm, which, admittedly, is more about jumping in the sack than mating for life.

The EAR 890 confounds reviewers in another way: It’s a straightforward thing, and while its design and execution are not without ingenuity, the EAR 890 lacks even such basics as hand-rolled capacitors or exotic metallurgy. Good God, this amp…has no story!

Description

The EAR 890 is, in designer Tim de Paravicini’s own words, a very conventional tube amplifier. Each channel uses its own 6AQ8 dual-triode as a differential pair, working in concert with another dual-triode, the ubiquitous 12AX7. The output section uses four tubes per channel in a parallel push-pull configuration: the relatively young KT90, which de Paravicini describes as Yugoslavia’s answer to the classic KT88. This beam tetrode, which shares some physical characteristics with the EL509 power tube used in the earliest EAR amps, is used as a tetrode, albeit not in ultralinear mode.

The payoff is a hefty, hell-raising 70Wpc, operating in pure class-A (footnote 1). Although de Paravicini says he strives for extended tube life—described for our purposes as a minimum of 10,000 hours—and thus maintains plate current within the realm of sanity, you still would not want to rest your hand on the metalwork of an EAR 890 that’s been playing music for any amount of time. As we say here in the Northeast US, “Bastid git hot, dunnit?”

Other interesting details: Hobbyists whose preamplifiers lack a balance control will be cheered by the presence of individual left and right channel-level controls, mounted on the rear panel. Nearby, a top-mounted switch allows the user to transform his or her EAR 890 into a 140Wpc monoblock; two-channel enthusiasts will then need to buy another 890, while monophiles can use a single one to intimidate the corner horn or old Quad ESL of their choice. Another switch toggles between unbalanced and balanced operation, the latter involving XLR sockets and an internal pair of custom-wound line transformers.

The 890’s output transformers are also de Paravicini’s own—he perfected the craft decades ago while working for Japan’s Luxman Corporation—and they present the user with separate taps for 8 and 16 ohm loudspeakers. And, finally, the auto-bias 890 requires little in the way of user intervention apart from working the On/Off switch, which is an orange plastic button. (But Tim: Are you sure that ivory, or perhaps even whalebone, wouldn’t sound better…?)

Notwithstanding an idiosyncratic approach to holding the tube cages in place (hard-to-reach bolts that extend into the circuit-board standoffs on each channel’s output boards), the 890’s construction is logical, robust, and beautiful. The parts count is surprisingly low—especially true of the tubeless power supply, which Tim de P describes as “a boring, conventional voltage doubler”—and the whole of the amp comprises four neat circuit boards: a small one for the balanced input trannies and associated bits; one large, central board for the driver section and power supply; and two output section boards. The smooth, heavy chassis has a finish of baked enamel, and the front of the amp is anchored with a thick brass faceplate, chrome-plated and polished to the proverbial mirror finish. Heavily chromed tranny covers with brass fixing nuts, another EAR calling card, complete the look.

Listening

At first I tried the 890 with my Lowther horns, replacing the Fi 2A3 Stereo amp I usually use. (My sample of the 890 already had several hundred hours on it, so I’m afraid I can’t speak to the issue of break-in time as it affects this particular amp.) I was extremely impressed, and although it may sound simpleminded to say so, the 890’s performance made me think of nothing so much as a Fi amp with even more headroom, and a little more drive and richness in the bass. Musically, the performance was faultless. Symphonies were appropriately forceful but never lacking in poise—and, to an equal extent, never lacking in musical flow. This was not at all the choppy, mechanical sound for which some SET devotees criticize push-pull.

But for the most part, I put all 70Wpc to work using the EAR 890 with my mildly insensitive Quad ESL-989 loudspeakers (Stereophile, November 2002 and May 2003). The combination proved to be among the most sonically faultless and musically satisfying I’ve had in my home.

In the past, I’ve used the word unspectacular in a derogatory way; this time, I mean it nicely. The EAR 890 was an unspectacular amp that gave me easy access to musically important details. When I used it to play Clarence White’s “Bury Me Beneath the Willow” (from the indispensable 33 Guitar Instrumentals CD, Sierra SZCD 26023-2), I heard clearly, for the first time, how the occasional “late” note attacks in this very early White recording weren’t mistakes at all, but rather deliberate attempts to push his cross-picking pattern off the tracks, so to speak, and to shift the upstroke—and thus the emphasis in each measure—in a way that made the tune more interesting. (Special note to guitar enthusiasts: Clarence White’s cross-picking pattern was virtually always down-down-up, down-down-up, not down-up-down, up-down-up, resulting in what I consider a more old-fashioned, mildly syncopated sound.)

The 890 also let me appreciate—if not for the first time, then certainly more easily than usual—Billie Holiday’s calm, understated delivery in the unsettling “Strange Fruit” (from the album of the same name, Commodore MVCJ 19214). I’m not sure why, but the 1930s-era recording, which merely sounds quaint through most gear, seemed “righter,” more serene, more inviting through this amp-speaker combination. Even the inevitable transfer noise, though still audible, imparted less distraction and fussiness to the listening experience.

Considering the Purcell music associated with the funeral of Queen Mary (I balk at a more specific title than that if only to avoid the ire of those who rightly observe that we don’t know for sure what was performed on that miserable day in 1695), the recording I most enjoy is the one made by John Eliot Gardiner in the late 1970s (LP, Erato STU 70911). At the end of this recording of the March, the percussionist plays a roll on a kettledrum tuned to C, the sound of which is then left to fade naturally (ie, it isn’t damped by the player). Bad amps—even enjoyable bad amps—èt this all wrong, refusing to let go of the sound and making mush of it in the process. Good amps give you a natural decay that dies away cleanly, letting you hear how the sound of a kettledrum at stage left can both splash off the assortment of brass instruments at stage right and induce them to resonate sympathetically. By this standard, the EAR 890 proved itself a very good amp indeed.

And that was just the sound; musically, the 890 made for a draining experience—but in the best possible way. The second sentence in the funeral service, “In the midst of life we are in death,” was uncommonly moving through this amp: The complex and often modern-sounding intervals carried by the four sections of the choir, in a continuous dynamic exchange with the organ, came through cleanly and clearly, leading me to wonder if the 890 produced much less than average in the way of both intermodulation and gross harmonic additives.

While on the subject of good English music, I recommend an impressive recording of John Tavener’s recent Ikon of Eros, for vocal soloists, solo violin, orchestra, and choir (CD, Reference Recordings RR-102CD). Throughout the work, violinist Jorja Fleezanis plays an almost continuous violin obbligato, which she does with remarkable consistency and sweetness of tone—and which the combination of EAR 890 amplifier and Quad ESL-989 speakers played with both convincing flow and lack of coloration. In fact, the only departure from utter timbral neutrality I thought I heard through this amp was an occasional excess of richness in the upper bass—which I noticed, for instance, in the plucked cello notes of the famous second movement of Borodin’s String Quartet 2 (LP, Decca SXL 6036, in a fine Speakers Corner reissue). But the effect was so very slight that, taken in the context of the Quads’ own slight tendency toward excess down there, and the possibilities that room reactions might produce the same thing, I hesitate to even mention it.

I don’t mean to give short shrift to the 890’s considerable output power, which is, after all, among its grandest raisons d’être. All I can say—which is considerable, I suppose—is that I never once heard the 890 get into any kind of trouble, even with the Quads in the largest of my listening rooms. This was as true of heldentenors as of Mott the Hoople.

Based on my experiences with other, earlier EAR amplifiers, I expected the 890 to excel at stereo imaging—and wasn’t in the least disappointed. Using a string quartet recording to describe a home music system’s imaging capabilities has become a bit of a cliché, so I’m a little embarrassed to still be thinking of that Borodin LP; in my defense, however, while I can’t think of a single stereo recording that really suggests the spatial qualities I hear in a live concert setting, of any type of music and from any seat, good chamber-music recordings such as the above-mentioned probably come the closest. And, yes, the EAR 890 reproduced the sense of depth and performer placement that I presume is a part of the original recording with both uncanny precision and the same sense of “rightness” with which it approached the music itself. (I could also point to how well it separated the voice sections on that Purcell LP, even going so far as to suggest some curve to the choir’s risers…)

Previous EAR experiences might also have led me to expect less than the best from the 890 in terms of rhythm and pacing; it’s been a few years since I heard it, but I remember the similarly beautiful-sounding 534 being somewhat less than jaunty with upbeat music. For whatever reason—improved damping? the essential sonic differences between EL34 and KT90 tubes?—I heard no such troubles here. In fact, when I used the EAR-Quad combination to listen to such songs as “Don’t Kill” and “A Little Concerned, That’s All,” from the great album Tough Love by Hamell on Trial (Righteous Babe RBR033-D), I had just as much fun as with our “party” rig (Naim amps driving Lowther horns—wheee!).

And the opening bars of Martin Sieghart’s altogether superior Schmidt Fourth (CD, Chesky CD143) had a rhythmic insistence I don’t get even with Lowthers (although perhaps that’s because so much of it takes place in the bass registers). And when the tempo picked up very slightly, some 12 minutes later—just before the transition to the second movement and its solo cello line—the EAR-Quad combination got the idea across effectively. All in all, there was nothing soggy or slow in the way Tim de P’s amp played rhythmically demanding music.

Finally, while most of my listening was done with my usual unbalanced interconnects (my own homemade solid-core silver), a sense of duty compelled me to try the 890 in balanced mode, too. (This despite the fact that Tim de Paravicini told me he believes “There are no sonic benefits that are peculiar to balanced [operation] that can’t be accomplished with unbalanced.” He went on to suggest that the 890 offers the choice simply to accommodate customers from a pro background, who are more comfortable working in a low-impedance connection context.) In particular, I tried a balanced cable set from DNM (see this month’s “Listening“), which is at least somewhat similar in construction and intent, if you will, to my reference.

Was there a difference? Actually, yes: While I heard no distinctions one way or the other in terms of flow or timbre or pitch or drama, I did in fact hear what I took to be a better, bigger sense of scale with the balanced cables. Sorry, Tim.

Back to where I started

As much as anyone else, I enjoy audio products whose strengths are plain and upfront and obvious—that is, as long as those strengths are the sorts of things that I care to hear. (Also as much as anyone else, I find it all too easy to fall into the trap of congratulating myself for hearing any difference at all, then buying whatever seems “freshest.” Self-control is as hard to come by at my house as at yours.) I hear obvious products all the time, and I’ve even reviewed a few for Stereophile.

But as often as that happens, I tend not to covet such products. The extra few notes of bass, the heightened sense of presence, the scary-quiet groove…they’re all nice, but after enjoying the luxury of having them in my home for 90 days out of my life, I can still do without them over the course of the days that remain.

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about the EAR 890 was that, with the exception of the Quads that I used it to drive, this was the first new audio product in a very long time that I caught myself scheming to buy.

Then again, look what we’re talking about here. A $5000 amp. Mama.

I have an idea. The EAR 890’s only significant flaw is in its engraved top plate, which is screwed to the top of that enameled chassis, and on which are inscribed the words “Technology at it’s best!” For one thing, the exclamation point is unnecessary, and its removal would lend the statement more in the way of, you’ll pardon the expression, quiet power—which I imagine would appeal to Mr. de P in any event. Second, and more critical, is the inappropriate use of an apostrophe, denoting a contraction where there is none—a common mistake, and one that I saw many of my fellow teachers make with impunity when I taught sixth grade. (I think they should have got the hot lead themselves. But it is—or should I say it’s—a sadly common thing nonetheless.) So I hereby offer my services as an English major to Tim de Paravicini, and I would gladly forgo monetary pay in favor of…oh, I don’t know, perhaps some sort of barter arrangement. I will wait to see what he offers in return. I’m not holding my breath.

An expensive amp, then, but one whose only apparent flaw is grammatical. I suppose it’s possible that the EAR 890, whose designer suggests that he could make an amplifier of precisely identical performance using transistors instead of tubes, sounds as good as it does because of its ability to step out of the way of good-sounding recordings. But if that’s so, I can’t help thinking it steps out of the way more gracefully than most.