Mark Levinson No 53 Monoblock Power Amplifiers

Original price was: R900,000.00.R280,000.00Current price is: R280,000.00.

Mark Levinson founded Mark Levinson Audio Systems in 1972, but sold it, and the right to market audio gear under his own name, to Madrigal Audio Laboratories, then owned by the late Sandy Berlin, in 1984. Harman International bought Madrigal in 1995. As well as Mark Levinson, Harman’s Luxury Audio Group now also includes digital processing pioneer Lexicon, speaker manufacturer Revel, and JBL Synthesis. The Mark Levinson brand is now headquartered in Elkhart, Indiana, at the Crown Audio facility, another Harman-owned brand. The No.53 ($25,000 each; $50,000/pair) is Mark Levinson’s first new Reference series monoblock since the No.33, way back in 1993, when Madrigal owned the company. Like other Mark Levinson products, it is manufactured at an independent facility in Massachusetts.Although it has a switching output stage, the No.53 is not a class-D amplifier. While the original rationale for the class-D technology was its efficiency—lightweight, cool-running amps that could produce a great deal of power—the No.53 is big and heavy, resembling the No.33—and it runs warm even at idle. It weighs 135 lbs, with claimed outputs of 500W RMS into 8 ohms or 1000W into 4 ohms, 20Hz–20kHz, at no more than 0.1% total harmonic distortion.

What’s wrong with class-D

Without going into too much tech detail, class-D, aka “switch mode,” amplifiers are more efficient than class-A or -B designs because their output transistors are either full on or full off. Rather than produce a higher-voltage version of the input signal, a class-D amp produces a high-frequency pulsed rectangular waveform: its transistors alternately connect the output to the positive and negative supply rails, with no in-between state. If the width of each pulse can be made proportional to the input signal’s instantaneous level, the power delivered to the speaker over time from this “pulse width modulated” (PWM) signal will be equal to that of a conventional amplifier. When this PWM signal is low-pass filtered, the theoretical result is the original signal at a much higher voltage, just as you get from a class-A/B amplifier.

Of course, producing those proportional pulses in the first place and then perfectly filtering the squarewave are no mean feats. What’s more, the high-frequency pulse signal will “broadcast” RF energy at upward of 300kHz.

Mark Levinson’s innovations

The No.53 uses what Mark Levinson calls a patented, multistage “very high speed switching amplifier technology,” Interleaved Power Technology (IPT), which is claimed to offer significant advantages over prior switching-amp topologies.

In a conventional class-D amplifier, one output transistor connects the output to the positive voltage rail, another connects it to the negative voltage rail. It is very important that when one transistor is turned on, the other must be turned off and vice versa, otherwise the positive and negative voltage rails will be short-circuited and the amplifier will self-destruct. However, because one transistor will be turned off before the other is turned on, there will be a short period of “dead time” when neither is turned on. This is analogous to crossover distortion in a conventional class-B amplifier.

ML’s engineers set out to develop a new PWM output stage designed to overcome these limitations. The transistors switching the positive and negative voltage rails to the load in Levinson’s “class-I” topology are each connected to the load via a large air-cored inductor and to the opposite voltage rail via a diode. The result is a stable amplifier with an effectively doubled switching frequency. Modulating the duty cycle of the 500kHz switching frequency of each transistor results in a 1MHz PWM output signal but without producing anything like the usual amount of ultrasonic noise. So minimal are the ultrasonic artifacts in the No.53’s output, it is claimed, that, rather than requiring a sonically degrading brick-wall filter, all that’s needed to remove them is a simple notch filter.

The No.53 uses four interleaved class-I/IPT stages in a balanced bridge configuration, to produce an effective PWM switching frequency of 4MHz. This allows the No.53’s signal bandwidth to be extended to 100kHz.

Four Subsections

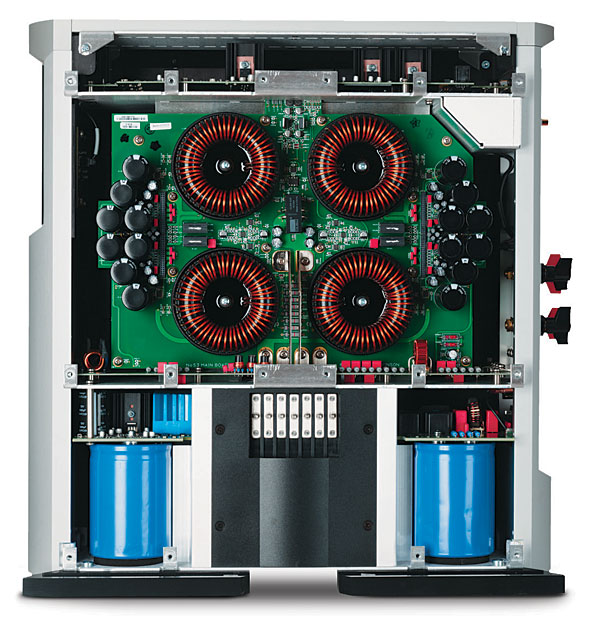

The No.53’s interior is divided into four sections: the single-ended and balanced inputs (SE signals are converted to balanced and remain so throughout the No.53), a modulation section, the amplifier itself, and the power supply. A six-layer printed-circuit board containing about 1500 parts incorporates the four isolated IPT modulator circuits, as well as the proprietary Link2 and MLNet system-control functions and the No.53’s protection circuits. The output stage includes multiple high-voltage, high-current, high-frequency vertical MOSFETs and eight air-core (nonferrite) inductors said to be virtually immune from saturation at high current levels.

The power supply is at the base of the tower, and includes a large toroidal transformer, 188,000µF of capacitance in the main supply, and an additional 105,600µF of “local” capacitance. While one of the supposed disadvantages of amplifiers with switching output stages is a low damping factor, due to the output low-pass filter, ML states that the No.53 has a very high damping factor, which allows the speaker to see a “virtual short circuit path back to the amplifier” that limits the effects of back EMF and results in tight, deep bass.

The result is a powerful amplifier capable of enormous peak current delivery, “tremendous” headroom, operational stability, improved electrical and thermal efficiency, and substantially reduced mass.

Setup and Use

The No.53 is about as tall (20.9″) as it is deep (20.4″), but only 8.4″ wide, with carrying handles cleverly integrated into the curved front and rear faáades. Nonetheless, carrying one was not easy. Once they were in place, it was easy to make connections on their open, uncluttered rear panels. In addition to the RCA and XLR inputs, each panel has two sets of sturdy speaker terminals fitted with wide, flanged, easy-to-grip plastic nuts. There are also low-voltage mini-plug trigger inputs and outputs for signal-sensing turn-on, Link2 inputs and outputs, and an Ethernet port to allow you to connect the No.53s to your computer network. Doing so allows you to connect to the amplifier’s internal Web page with Internet Explorer, where you can modify the network setup, pull down a window to select one of four levels of intensity for the front-panel display, get basic status information, and track system-related error messages. In the event of a problem, this page will also be used by Mark Levinson Customer Service.

The ML Net protocol allows you to control two or more network-capable Mark Levinson products simultaneously from their Ethernet ports by setting up master and slave units. If the system doesn’t work right, make sure the master and slaves are “properly daisy-chained.” A front-panel status LED blinks differently, depending on what it’s trying to tell you.

When I first listened to the Mark Levinson No.53, its sound most reminded me of that of the Soulution 710 stereo amplifier that I reviewed in August 2011: fast, precise, detailed, somewhat lean overall, and more interested in correctly producing the initial transient than in fleshing out the texture-producing sustain. In “Yulunga,” from Dead Can Dance’s Into the Labyrinth (LP, 4AD), the hand drum crackled with taut definition, while the metal percussive accent that floats above was noticeably and appropriately metallic. The shaker was reproduced as cleanly as I’ve ever heard it; the sound of each seed (or whatever) inside it was precisely rendered and compactly sized.But the hand drum, too, sounded somewhat metallic. Clean, orderly, and precise, with a pitch-black backdrop, the No.53’s reproduction of this album was in many ways compelling, though stage depth was less pronounced than I’ve grown accustomed to, and the picture was generally dry.

As promised, the No.53’s bottom end was fast, taut, and very well extended through the Wilson Audio Specialties Alexandria XLF speakers (review in the works)—the bass transients in “Yulunga” were superbly defined. The depth-charge bass notes a few minutes in had full extension and notably clean delineation of the transients, though they could have used some additional weight, and definitely more body. The amp gripped that bass bomb and held it cleanly until it was time to let it go. Then it seemed to dissipate unusually cleanly and quickly.If you like your midband rich, you won’t get it from the No.53; but if you like it transparent, open, and lightning-fast, that the ML could do—it was much like the Soulution 710 in that way.

As promised, the No.53’s bottom end was fast, taut, and very well extended through the Wilson Audio Specialties Alexandria XLF speakers (review in the works)—the bass transients in “Yulunga” were superbly defined. The depth-charge bass notes a few minutes in had full extension and notably clean delineation of the transients, though they could have used some additional weight, and definitely more body. The amp gripped that bass bomb and held it cleanly until it was time to let it go. Then it seemed to dissipate unusually cleanly and quickly.If you like your midband rich, you won’t get it from the No.53; but if you like it transparent, open, and lightning-fast, that the ML could do—it was much like the Soulution 710 in that way.

I sat down and began cycling through CD-resolution and higher-rez files, using an iPad to control my Meridian (née Sooloos) Digital Music Server via Meridian’s Core Control app. Decoding duties were performed by MSB’s Platinum Diamond DAC IV, which produces the best digital sound I’ve ever heard, particularly in terms of top-end cleanness, transient clarity, image size, and three-dimensionality.

I went through everything from “It’s Good News Week,” by Hedgehoppers Anonymous, to Howlin’ Wolf’s “Smokestack Lightning,” to Arvo Pärt’s Kanon Pokajanen, with the Estonian Philharmonic and Chamber Choir conducted by Tõnu Kaljuste (ECM New Series 1654/55), and noted the overall transient precision, superb if not unprecedented speed and clarity, resolution of inner detail, and black backgrounds. However, there was also a dose of listening fatigue partly caused by high-frequency hardness, and partly by the overall dryness, which also produced well-rendered outlines but little in the way of nuanced textures: all outer shell, very little creamy center.

Women’s voices were problematic through the No.53. For instance, “Fields of Gold,” from an out-of-print edition of Eva Cassidy’s Songbird (LP, S&P 501), features a pristine recording of her stunningly pure voice, bathed in reverberation. The voice should be pinpoint sharp in the best sense of that phrase, compact in size, and well separated from the engulfing reverb. That reverb should be a cushion, not a trap. Through the No.53s Cassidy’s voice was pinpoint sharp but the reverb, instead of being airy and ethereal, sounded like a hard haze that obscured detail at low levels and became fatiguing at higher ones. Reverb should be experienced as an event separate from the main one, but with every record or file I played through the No.53s, instruments, voices, and reverb seemed to blend into a single event.

As seems to be the case with switching amps, no matter how carefully designed, the higher in frequency the music goes, the more problems there are. That also holds true the more you turn up the volume. Generally speaking, the louder I played the No.53s, the more pronounced the haze. The more high-frequency content in the music—women’s voices, cymbals, reverberant backdrops—the more the haze intruded on and obscured the images, forcing me to turn down the volume.

Singer Johnny Hartman’s baritone on John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman (LP, Impulse!/ORG 017) should produce a warm, rich, graceful, round, full voice between the speakers. The No.53s managed great clarity and edge definition, as they did with everything I played, analog or digital, but Hartman’s voice sounded grayed-out. Turning up the volume helped fill it in a bit, but as soon as Hartman or Coltrane accented something with an increase in loudness, particularly in the upper octaves, the haze seemed to increase, pressing against an imaginary wall that prevented it from expressing itself spatially. The soundstages of familiar recordings were noticeably flattened.

Cables to the Rescue?

I wondered if swapping out the TARA Labs Omega Gold speaker cables, with their airy, extended top end, for something warmer and more inviting, might help. I had on hand the softer- and richer-sounding Stealth Dream V10, as well as AudioQuest’s William E. Low Signature Series. I tried both. The overall balance became warmer and more burnished on top, but that seemed to mute the clarity of the very top end and the transient precision—among the No.53’s best qualities—while accentuating and laying bare the haze and glare still inhabiting the upper octaves.

Conclusions

I found the sound of the No.53 very fast and clean, though very lean. They resolved a remarkable amount of genuine detail but were harmonically threadbare, sounded somewhat hard and mechanical on top, and had a hazy overlay just below that. The bass was fast, lean, taut, and well damped—rhythm’n’pacing were among the No.53’s strongest suits. But overall, the nature of the sound induced listening fatigue. I rarely listened for more than an hour at a time, which for me is unusual.

Mark Levinson’s No.53 is beautifully built, technologically impressive, and physically attractive in an industrial high-tech kind of way. If you prefer powerful, muscular solid-state amps—I’m already sold on them—and you’re shopping in the $50,000 range, find a retailer who can demonstrate for you a pair of No.53s, and give them a long, serious listen. You might like the sound, especially if your goal is to firm up a system that sounds too warm and loose. But be careful—at first, you might be bowled over by their speed, clarity, and seeming resolution of detail. Longer-term listening, however, might reveal that those pinpoints of detail appear because the surrounding context has been stripped away.

Description

Specifications

- Design: Solid State Monoblock Power Amplifier; Switching Output Stage

- Power: 500 Watts RMS into 8 Ohms, 1,000 Watts into 4 Ohms

- MFR: 10 Hz – 20 kHz, ± 0.1 dB

- THD+N: Not Specified

- S/N: 85 dB (@ 1 Watt into 8 Ohms)

- Inputs: XLR and RCA

- Input Impedance: 100 kOhms Balanced (XLR), 50 kOhms Unbalanced (RCA)

- Outputs: Two Sets of Speaker Binding Posts for Bare Wire or Spade Lugs

- Other Connections: Ethernet, Link Port (connection to othe Levinson products), Trigger

- Dimensions: 20.4″ H x 8.4″ W x 20.4″ D

- Weight: 135 Pounds

- MSRP: $50,000/pair USA