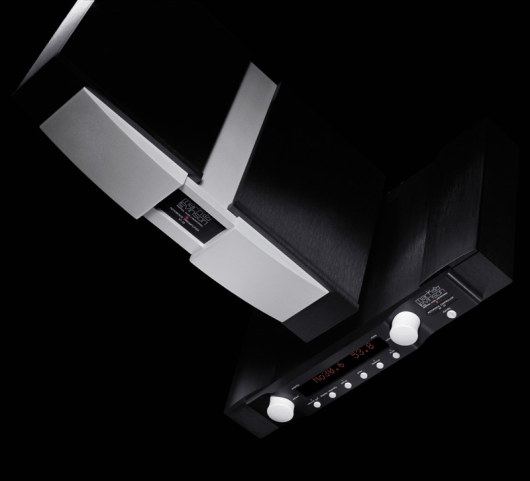

Mark Levinson Reference 32 Preamp (One Owner – MINT)

Original price was: R330,000.00.R120,000.00Current price is: R120,000.00.

Description

Mark Levinson No.32 Reference preamplifier

Power supply matters

Power supply mattersWhen phono was the primary source and all circuits were single-ended, a separate power supply was the most obvious characteristic of a high-end preamplifier design. Even today, many low-gain line stages use an external power supply, despite the fact that, as Madrigal points out, balanced circuitry is generally less sensitive to noise. In fact, Madrigal feels the cost of the additional chassis far outweighs the benefit. They prefer reaching their technical and performance goals with properly implemented balanced circuitry, relay switching, and microprocessor control.The No.32 takes an evolutionary step forward by packaging the power supply, control circuitry, and display together in one chassis: the “dirty box” Reference Controller. The audio circuitry, more sensitive to noise, comes in a separate chassis: the “clean box” preamp itself. AC power supplies, microprocessors, LED displays—anything that generates noise—is thus physically separated from low-level audio signals. The only element the audio circuits are exposed to is quiet, regulated DC power and the audio signal itself.Two master supplies are located in the center section of the sleek-looking Controller. One supply is dedicated to control and communications, the other to the audio circuits. A combination of inductors and capacitors prefilters the AC line and isolates the two master supplies from each other. The supplies use custom-designed transformers with multiple secondary windings to improve isolation between circuit blocks. Separate rectification, filtering, and regulation circuits supply DC to the control/communications circuits, to a Levinson No.25 phono preamp, for the optional phono modules installed in this unit, and to the 400Hz oscillator circuits used in power-supply regeneration. An external ground terminal is provided for systems in which the AC mains receptacle lacks a separate ground pin.AC power regeneration refers to the DC supply feeding the voltage gain stages. This supply is derived from an AC source generated within the device itself. This technique is expensive but very effective, according to Madrigal. In the No.32’s Controller, a 400Hz oscillator generates the AC source for the preamplifier’s audio power supplies, replacing the 50/60Hz reference provided by your local utility. One advantage to operating at 400Hz as opposed to 60Hz is that the transformers operate more efficiently and thus generate less heat. Another advantage is that the filter capacitors are charged more quickly, yielding a smoother DC supply from the filter caps. Equivalent filtering from a 60Hz supply requires larger capacitors, and thus higher ESR (Effective Series Resistance) at high frequencies. Because 400Hz oscillators and power-supply components are commonly used in aircraft electronics, high-quality parts are readily available.The 400Hz oscillators supply individual left- and right-channel isolation transformers, followed by rectifiers and discrete DC voltage regulators. The outputs supply clean, stable 400Hz power in the adjacent left and right “towers” capping the Controller. Each tower, machined from a solid block of aluminum, contains the power supply for its respective audio channel. An isolation transformer mounted inside the block further decouples the audio-regulation stages from the 400Hz oscillator amplifier. Soft-recovery diodes rectify and filter the transformer’s output, which is then regulated with a low-noise, high-speed voltage regulator designed specifically for the task. Separate cables supply the DC output to each channel. While 2m DC cables are supplied with each unit, lengths of up to 8m are available to expand placement options; a nice touch.

Microprocessor control

While microprocessors offer lots of flexibility, they’re typically noisy little buggers that can pollute low-level audio signals. In the No.32, aside from being located in the separate Controller chassis, the controller module itself (and its microprocessors) sits in a shielded enclosure that is easily removable for hardware updates. In addition to communications, the No.32’s microprocessors control volume, signal routing, and other switching functions.

While microprocessors offer lots of flexibility, they’re typically noisy little buggers that can pollute low-level audio signals. In the No.32, aside from being located in the separate Controller chassis, the controller module itself (and its microprocessors) sits in a shielded enclosure that is easily removable for hardware updates. In addition to communications, the No.32’s microprocessors control volume, signal routing, and other switching functions.

The lucky audiophile using a No.32 can easily name inputs, select mono modes, set mute level, or program gain offset and overall level for individual inputs from the front panel or remote. And, miracle of miracles, you can actually adjust phono loading during play, via the remote or at the front panel! When ML trumpets that cartridge loading has never been simpler or easier, they’re not just whistlin’ Dixie! Man, that’s luxury. Just think of it—you can tune each LP during play, with hardly any effort, from the comfort of your listening chair. Ahhh…pay your big bucks, get spoiled.

Communications

Despite its purist two-channel status, the No.32 Reference participates at the high level of intercomponent communication that is central to the Mark Levinson systems philosophy. Like other recent ML products, the No.32 is built around a software-based operating system that can be upgraded without even opening the chassis: New operating-system software can be downloaded into the preamp via its RS-232 port. That also allows AMX, Crestron, and other, similar multi-zone control systems to communicate with the unit. The three 3.5mm mini-jacks on the rear panel offer DC trigger output (5-12VDC, pulse or level), DC trigger input, and remote IR input control. Two PHAST communications ports offer forward-compatibility with future ML products, as well as other PHAST-equipped components and systems. A separate amplifier control connector provides communications to the No.33 and No.33H amplifiers, as well as to the 300 series amplifiers, if you’ve got them.

While I didn’t make use of these communications subsystems, their very existence suggests the thoroughness and depth of engineering lavished on the No.32—right down to the elegant pair of white gloves packed with each preamplifier.

User interface

The No.32’s user interface is a miracle of thoroughness, finesse, and ease of use. The preamp itself has no buttons—just an LED to tell you it’s awake. The electromechanical isolation surrounding each of the Controller section’s unused inputs allows it to be programmed to act as a dedicated preamp for each individual input source. The two inviting, soft-hued knobs jutting from the Controller’s towers set volume and perform input selection. Secondary functions like balance, mute, and selection of recording source are accessed via small buttons ranged along the bottom of the central panel. Parameters for optimum performance for each source can be input, adjusted, and saved. The source selector toggles only among active inputs; ie, it presents only those sources actually connected to the system. Each source can be named in the alphanumeric display, and full control of all functions, with the addition of mono/stereo selection and polarity control, is available from the remote. The remote itself is a nicely designed, ergonomic hunk that’s easy to use and falls beautifully to hand.

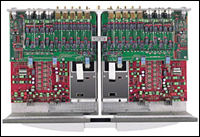

The preamplifier chassis’ casework gives the lucky user something of a visceral thrill. It’s a custom aluminum casting, machined and finished with a coating of conductive Irridite (clear chromate). This, per Madrigal, ensures a rigid, stable environment in which vibration and microphonic effects are well controlled. The left and right channels are separated by a solid aluminum divider wall (part of the casting), which seals each channel into its own environment. This prevents one channel’s electromagnetic noise from degrading the other channel’s signal. Since each channel is effectively isolated electrically and physically, the No.32’s stereo separation is equivalent, Madrigal claims, to that of two separate mono preamplifiers.

Power and control connections

Each channel is connected to the Controller by a 10-conductor, heavily shielded DC cable. Four conductors deliver regulated DC power to the preamplifier’s audio circuits; the other six carry DC control signals. More important, each channel’s microprocessor is active only when receiving control signals—otherwise they’re in “sleep mode” and entirely silent. A low-voltage, differential-drive control signal, buffered by optoisolators, issues commands. Except for the fraction of a second when the microprocessor is actually transmitting one of these commands, there’s nothing in the DC cables between Controller and preamplifier except pure DC.

And that means pure. The DC flowing from the Controller is further regulated with another low-noise, high-speed voltage regulator. Critical blocks such as the volume control and the optional phono modules receive additional local supply regulation. “Liberal use of local bypass capacitors assures an optimal electrical environment for critical audio circuit components.”

Why is it so easy to believe them?

Inputs

The No.32 sports eight inputs: three on balanced XLR connectors and five on single-ended RCAs. The optional phono modules include two additional inputs, either balanced or single-ended. As alluded to before, unused inputs have both their signal and ground connections open to prevent noise from seeking a path through the preamp’s well-grounded chassis. An R/C network hinged at 1MHz provides RF filtering for each input. An instrumentation-grade T-switch topology keeps the No.32’s inter-input crosstalk “exceptionally low.” Even with adjacent inputs unassigned and unterminated, isolation is greater than 120dB. With other source components connected, as would usually be the case, isolation improves to a rather startling 140dB. Madrigal proudly points out that that’s about 100 times quieter than their “already excellent” No.380S. The special relay switching scheme, circuit layout, and shield bars tied to the system ground are responsible for the high level of performance.

Circuitry

The No.32 is the first Mark Levinson product to use Arlon 25N circuit boards in the active preamplifier and phono-module circuits. Madrigal explains that this material offers superb dielectric properties and was chosen after extensive listening tests. A quick visual inspection of the left- and right-channel circuit boards reveals them to be symmetrical, but only in a general way—individual parts are not mirror-imaged to the opposite channel.

The No.32 is the first Mark Levinson product to use Arlon 25N circuit boards in the active preamplifier and phono-module circuits. Madrigal explains that this material offers superb dielectric properties and was chosen after extensive listening tests. A quick visual inspection of the left- and right-channel circuit boards reveals them to be symmetrical, but only in a general way—individual parts are not mirror-imaged to the opposite channel.

“The layout was developed by hand for electrical rather than visual symmetry. We have learned that this is the only way to approach circuit layout, using exhaustive listening tests as the measurement of success—to understand this point is to recognize the beauty of the circuit itself.” That’s devotion.

Single-ended signals have their common-mode noise (ie, noise present on both signal and ground) rejected at the input stage. Fully balanced instrumentation amplifiers are used in the gain stages, and each input can be separately adjusted for 0, 6, 12, or 18dB of gain. This allows the volume control to work in its optimum range even with sources of substantially different output levels.

Optional phono modules

Phono modules can be installed in the No.32 for analog diehards like me. The channels are separately enclosed in mu-metal shielded boxes that slide into the preamplifier chassis on either side of the channel divider wall. The positioning is anything but accidental; it’s optimized for the power supply and signal path, and being close together allows for easy connection of tonearm cables. Each phono module is fitted with two independent input connectors to accommodate systems in which two tonearms or turntables are in use. Phono modules are available with each input configured for either single-ended (RCA) or balanced (XLR) connectors. The review module had two pairs of RCA inputs so I could run the Forsell and the SpJ/La Luce turntables!

Each input’s settings are independent of the other, allowing custom setup and optimization for two different analog sources. A defeatable infrasonic filter, resistive and capacitive loading, and gain—all can be selected independently for each input. A fine trim adjustment for balance allows the rapidly-getting-spoiled owner to compensate for the small channel imbalances found in many cartridges. Couch potatoes rejoice! It’s all doable from the remote control while you’re sitting on your can in the listening chair!

Volume control

The No.32 Reference introduces Mark Levinson’s new active attenuator. The attenuator modules are constructed on their own four-layer Arlon boards, where local power-supply regulation and bypass capacitors make for clean power and optimum isolation. An array of precision resistors provides attenuation in 0.1dB steps down to -57.0dB, at which point the steps increase to 1.0dB. In total, this hardware provides for more than 65,000 steps, allowing the No.32’s “stepped attenuator” to act—and sound—like a continuously variable control. Optimal volume was always a cinch to find, even though one has to lean on the remote and hold the button down for longer than usual as the display moves up or down in 0.1dB steps. But it’s churlish to complain—repeatable and precise settings make for happy reviewers. If you’re in a hurry, spinning the knob on the Controller steps through volume settings in a more lively manner.

Outputs

The No.32’s output contains high-performance buffer amplifiers that, Madrigal claims, feature low noise and distortion, low output impedance, high current capability, and broad bandwidth. Two pairs each of balanced (XLR) and single-ended (RCA) connectors are available at the main outputs. Single-ended and balanced outputs are independently buffered to allow simultaneous use of both connector types without sonic compromise. Buffered record outputs are provided on one pair of balanced (XLR) and two pairs of single-ended (RCA) connectors.

With the No.32, Mark Levinson has institutionalized the art of engineering tweakage! To their heroic efforts, jaded though I may be, I doff my hat.

32 and Reference to go

I begin my description of the No.32’s sound by simply saying…Patricia Barber. Her new album, Companion (Premonition/Blue Note 5 22963 2), is just phenomenal. It’s her first recording with the Hammond-B3, and it’s the best yet from engineer Jim Anderson. What a babe! What a talent! What a recording! [It’s this issue’s “Recording of the Month.”—Ed.]

Start with “Use Me,” that ol’ Bill Withers warhorse. For the sheer enjoyment of it, groove to the long acoustic-bass exposition. At first, you might not have a clear idea where it’s going (although I, for one, was content to follow the musical exploration with much anticipation and enjoyment). Then, suddenly, out pops that familiar tune: “If it feels this good getting used…” Yeah, baby.

Let’s get audiophile. Soundstage width, depth, and “population,” as it were, never sounded better. Not overall as screamingly transparent as some preamps manage, but I came to understand that the No.32 put its many talents into the totality of its presentation, so transparency as an end in itself was out; the No.32’s version of transparency was dictated more by the overall balance of its presentation. For instance: The audiophile concept of “air”—the sense of the original acoustic—is inextricably tied up with transparency…and with speed, pace, tonal color, harmonics, bloom, decay, and so on. In this regard, the totality of music as presented by the No.32 was astonishing.

The ambience of the Green Mill in Chicago, the club where Barber got her start, was beautifully rendered; I almost felt a part of the proceedings. Check your system’s bass prowess with that involved acoustic bass solo that kick-starts “Use Me.” Feel the pull and release of the strings during the long sustain just before the familiar riff emerges. Feel yourself pulled into the moment as the percussion comes up, followed by Barber’s voice and strong stage presence. Musically, her take on “Use me” is wonderfully considered, the acoustic perfectly set up by the No.32. Engaging, rich, rife, extended, airy, smooth, and oh so palpable, the unforced detail rushed through the JMlab Utopias at an incredibly high level. Pace, speed, leading-edge definition, and pitch differentiation come no better than this.

Interesting audiophile tidbit: The sound of the Hammond B3 in its upper registers can be extremely revealing of a system’s ability to deliver the goods in the treble. If your tweeter’s at all touchy or hard, too close to its breakup mode, or insufficiently damped from same, trust me—you’ll hear it with the B3.

And that goes for the rest of your playback chain. Cable a little bright? Cover your ears! Get that unique Hammond tonewheel character right and pleasing, and you’re saying something. The Hammond sound was simply incredible through the No.32/Klimax kombo, all lashed up with Synergistic Research Designer’s Reference Active Shielding and Nordost SPM Reference on the Utopias: extended, linear, powerful, yet perfectly integrated into the rest of the frequency spectrum. And yes, with just a hint of sweetness at the very top, like a cherry perched on that dessert you’d better not be thinkin’ of eatin’! Yummy.

But despite its hewn-of-a-piece presentation, I was floored by one special characteristic of the No.32: the enormous amount of unforced information passing through its circuits, from the quiet between the notes down in the noise floor to the most impressive of crescendos, and from the deepest bass fundamentals through to the top of its treble extension. As a result, of course, palpability—a quality I much prize—was much enhanced. In that way, the No.32 proved a rather intimate component: no secrets. I had the sense that the floodgates were open, the signal flowing unimpeded, the quality of the source components allowed to pass through and reach me, utterly unmolested.

Given this superb level of information, so much about individual recordings became more clear and available. The Barber club date glowed with a gorgeous, full palette of midrange tonal colors, sandwiched between a powerful, involving bass and sweet, open highs. Interestingly, especially in the midrange, I experienced this rainbow of tonal color as “cool” rather than “warm” or “euphonic”—very attractive, and not quite like anything I’d ever heard before. Not analytic, you understand, or dry, just there—and, I conjecture, unchanged from the source feed.

This enormous level of utterly natural detail was evident throughout the audible frequency range. I’ve been exploring deep-bass performance and enjoying myself groovin’ along to a great film soundtrack called Run Lola Run (TVT 8220-2): technoid Art of Noise marries Morcheeba, and David Lynch and Angelo Badalamenti give away the bride under the watchful eye of a moody German director thrown in for laughs. Listen to one of my favorite tracks, “Casino,” and enjoy the splendid midrange for a bit. Commercial releases should all sound this good. Despite the complexity of the score, just before the 3:00-minute mark, a crescendo begins whose stunning sonic boom doesn’t crest until around 3:54. How’s the quality of that bass in your system?

The No.32 passed awfully deep and powerful bass, but not the single-note sonic depth charge some equipment dishes out. Rather, its fundamentals and full palette of tonal color, shading, control, and pitch differentiation down at the bottom were so well rendered they almost imploded my chest! Above, that wonderful and engaging midrange physically pulled me into the music, while the gorgeous highs beckoned me on seductively.

There’s some primeval connection between sound and emotion. I was feeling it deep. Somehow, the level of my involvement was tied in to that spectacular level of detail. It gave my little audiophile brain more than enough information to achieve that immersive, goosebump-inducing sonic state I crave—that all of you reading this crave, I presume.

As I had with the new Pat Barber recording, I noticed a few molecules of darkness at the very top of the range that seemed a part of the No.32’s presentation. But, as before, slightly tuning the high frequencies by rotating the flanking ASC Studio Traps to show a bit more reflective than absorbent surface to the Utopias’ drivers opened up that just-“objectionable” (only to a maniac) touch of somberness.

With sudden inspiration, I spun Jon Hassel’s Fascinoma (Water Lily Acoustics WLA-CS-70-CD), one of my favorite releases from producer/engineer/analog maven Kavi Alexander. The smooth and heady detail I’ve noted enhanced this purist recording’s acoustics immeasurably; the palp factor was enormous, allowing an easy, plush acoustic to develop, especially in the midrange, where, it is said, music “lives.”

Why even put it that way? Because I think the idea of “where it lives” is important, and relates to that primitive sense humans seem to have for sound and music. It’s alive! The closer a component gets you to that feeling, the better it is, in my book. I was completely captivated listening to “Secretly Happy” from Fascinoma. At that point, I’d have told anyone how happy I was!

Spoiled. K-10 and I are so spoiled.

Studio Traps or no, I found the very top of the No.32’s frequency band a hair less alight and bright than those of some other preamps. But again, the beauty of the overall gestalt was perfectly served. My toes wriggled with pleasure during the flute solo on “Happy,” the track’s analog hiss very much a part of the total sense of ambience—almost, I thought, appropriate to the music.

Although a lot of people gasp at the depth typically heard from our system, to me the No.32 sounded only medium-deep. This in itself means nothing except to be taken note of. Each manufacturer has its perspective, its take on the ideal listening position—row B, row M, whatever—and, I suppose, they consciously or unconsciously tune for it. Or perhaps it’s a result of the characteristics of the circuit. The Nagra PL-P sounded very much front-and-center, as did the Class&233 Omega preamp. The YBA 6 Chassis sounds more mid-hall in perspective, the BAT VK-50SE somewhere in between.

The No.32’s view was, like everything associated with it, carefully thought out and presented. The resultant sound was intimate and seductive in that way. The listener is cordially invited in to enjoy the musical experience. I imagine the No.32 saying, “No no, not to worry; if you can afford me, I expect you’ll enjoy it.”

Analog doings

I picked up A Jazz Portrait of Frank Sinatra (Japanese Verve UMV-21) for four bucks at a local street fair. Score! Recorded in Paris on May 18, 1959 “under the personal supervision of Norman Granz,” with Oscar Peterson on piano, Ray Brown on bass and Ed Thigpen on drums. I can’t remember “seeing” and hearing Oscar so totally enjoying himself making music. It was as if the No.32’s phono section allowed me to hear the very weight and momentum of his hands and arms, his very body behind the keystrokes. I found it easy to experience his movements as he jived around, stabbing joyfully at the piano. Man, it was organic!

I followed with my fave, Bags Groove (OJC-245), with Miles and company, then the delicious Ellington Jazz Party in Stereo (original six-eye Columbia CS 8127). Greedy for more, I spun Miles’ Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (Fontana 836 305-1) and Johnny Griffin’s Studio Jazz Party (Riverside RLP 9338).

Almost sated, I spun Basie Jam #2 (Pablo 2310-786), from that same heavy-duty street-fair score. I found the ability and ease of adjusting cartridge loading on the fly totally fabulous, and settled generally on 330 ohms to sufficiently damp the soupy roar of RFI that exits between the Empire State Building and the World Trade Center—a torture test if ever there was. Nor did 330 tamp down the top end too much. This was fine with the Grasshopper IV GLA, and, depending on the time I was listening—late nights and weekends were slightly less noisy—1k ohm sounded a shade better with the Clearaudio Insider and the Koetsu RSP.

But all cartridges loved the No.32. On the Basie disc, the No.32 set up a well-populated, airy soundstage. The naturalness and shimmer, the elegance of the sonic edifice the No.32 created were wonderfully palpable.

I reeled from the joy of all this sonic nirvana. I wondered—what have I done to deserve this? I’m sure many of you will shout “Not enough!,” and I almost might agree. I can’t remember the last time I gorged on vinyl like this or enjoyed it so deeply. Kathleen had to force me to shut down the system and go to bed.

It definitely adds up to more than 32

I have a friend, a Juilliard graduate with a great pair of ears. (His taste in cigars isn’t bad either.) His first reaction on hearing the No.32 Reference at full tilt was to drop his jaw at its ease of presentation. After a few more minutes:

“Hey, this is the one! Where can I get it? When can I afford it?” he wailed.

I know what he means. Audio is hell.

Except in the best gear, greater apparent detail is often thrust at the unwary listener as thin, bright, over-etched sound—although I’m bound to note that, in the High End, this is becoming far less the case than ever. Compared to only a few years ago, outstanding performance is available for quite modest prices. (And kudos to the industry for the convergence of solid-state and tubed sound, if at varying levels of overall refinement.)

But when you shell out the long green for gear like the Mark Levinson No.32 Reference preamplifier, you get a product that delivers on that promise of More and Better like nothing I’ve heard to date—a true Reference product whose name matches its performance. Bravo.

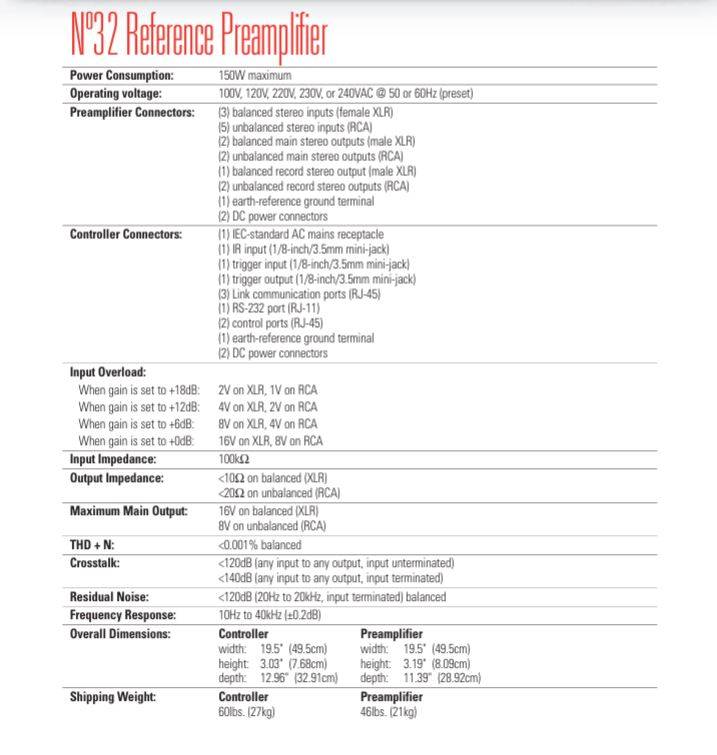

Mark Levinson No.32 Reference Preamplifier

by Marc Mickelson

Review Summary

|

Amidst the many buttons, knobs, LEDs, and processing modes of home-theater preamp/processors, the plain-Jane simplicity of a stereo preamp of the sort audiophiles use in their systems seems like a quaint anachronism, a rusting two-seat roadster with sticky manual transmission in the days of sleek sedans that run on gas or battery power and have built-in DVD players and navigation systems. Audiophile preamps often use vacuum tubes and lack even the most basic of user niceties, while their home-theater counterparts are anything but limited, having multiple digital processing modes, support for multiple-zone use, and various means of connectivity, all of which their owners require.

But then there is the Mark Levinson No.32 Reference, a two-channel preamp that bridges the gap between the minimalism of the audiophile world and the rich functionality of home-theater systems. The No.32 will please purist audiophiles who need their preamps to function as true control centers for strict stereo or combined stereo/multichannel systems, and it will do so with the sort of ergonomic class for which Mark Levinson products are famous.

Creating a Reference

The $15,950 No.32 Reference is the oldest of three Mark Levinson stereo preamps currently available (there are also the No.320S and No.326S), having been introduced in 1999, and the only one that is a two-chassis design. It is also the only Mark Levinson preamp to warrant the company’s Reference appellation, which designates it as the company’s most technologically advanced and best preamplifier.

While separating a preamp’s power supply from the rest of its circuitry is not a new idea, the No.32 takes this notion to a very logical extreme. Separated into discrete chassis is all of the audio circuitry (which Mark Levinson calls the Preamplifier; 4 1/8″H x 19 1/2″W x 11 3/8″D and 26 pounds) and anything that could affect its performance, including the power supply, the LED display, and all of the control functions (referred to as the Controller; 3″H x 19 1/2″W x 13D and 40 pounds). Therefore, only the audio signals, control commands and DC power enter the Preamplifier, with AC and any communication connectivity entering the Controller. This is an ingenious design and one that other companies, most notably VTL and McIntosh, have adopted for their highest-end preamps.

But the design innovations don’t stop there. The No.32 Reference regenerates the power used for its audio circuitry to ensure absolute purity. This is accomplished by two independent power supplies that are dedicated to the audio circuitry. The DC from these powers an optimized power amplifier that produces only a pure 400Hz sine wave, which is then rectified, filtered and re-regulated to create the DC power for the No.32’s Preamplifier circuits. The No.32 Reference is also a dual-mono design that’s balanced from input to output, including the single-ended inputs, whose signals are converted to balanced after entering the Preamplifier and are handled in balanced fashion thereafter.

There’s more. The No.32’s discrete attenuator uses 66 surface-mounted resistors per channel and provides volume control in 0.1dB increments. The unit’s expensive Arlon 25N circuit boards are said to outperform those of previous “S”-series Mark Levinson products, which are made of cyanate ester. Interestingly, the engineers at Mark Levinson have found that Arlon 25N is only beneficial for circuit boards that house active devices, while boards from other materials, including FR-4 glass epoxy, are used elsewhere. Their take: “We understand that the No.32 represents a big investment for anyone to make in their music system, and are careful to ensure that it is money well spent.”

Connectivity is immense. The No.32 has eight pairs of inputs (three balanced and five single ended) and four sets of main outputs (two each balanced and single ended). There is provision for an internal MM/MC phono stage (I didn’t test it, but it is rumored to sound incredibly good), which is also dual mono and fully balanced. Other than its inputs and outputs, the line-stage-only No.32 Reference has a grounding post and a pair of DC-power inlets on the back of the Preamplifier, and the IEC receptacle, a host of connectivity ports, and DC-power outlets on the rear of the Controller. The front of the Preamplifier has only a power LED, while the Controller has the knobs and buttons used to facilitate input switching and programming. Relevant functions are duplicated on the No.32’s hefty remote, which makes up for its physical clunkiness — it is broad and doesn’t fit very well to hand — with its ability to hit its mark with every command.

As with the Mark Levinson No.383 integrated amplifier I reviewed a few years ago, the No.32’s software-controlled user interface is state of the art. It allows you to name and set the offset for each input (and turn unused inputs off), set the volume control’s maximum level, set the mute level, and program a host of other characteristics of the No.32. The dot-matrix LED display, which is used for programming, is large and easy to see even from across the room, but you can dim it or turn it off completely if you find it distracting.

The No.32 Reference sets the standard for customization and user-friendliness for high-end audio electronics. More than any piece of audio equipment with which I am familiar, the No.32 can be tailored to your system and become an extension of the way you listen to music. It’s a joy to use.

Review system

The No.32 Reference took its place among some equally expensive equipment. Speakers were Wilson Audio MAXX 2s, while amplifiers were Lamm ML2.1 and M1.2 Reference monoblocks as well as a Blue Circle BC202 stereo unit near the end of the review period. Source components were an Esoteric X-01 CD/SACD player, an Audio Research CD3 Mk II CD player, and Zanden Audio Model 5000 Mk III DAC used with Zanden Model 2000P or Mark Levinson No.37 transports via Audience Au24 or i2Digital X-60 BNC-terminated digital cables. Interconnects and speaker cables were from Cardas (Golden Reference), Siltech (Signature G6 Compass Lake and The Emperor) and AudioQuest (Sky and Volcano). The preamp for comparison was a Lamm L2 Reference.

Power cords for most of the review period were from Shunyata Research — Anaconda Alpha, Anaconda Vx, Python and Taipan — as was the Hydra Model-8 power conditioner. Because the No.32 regenerates its own power, I was curious to hear whether different power cords would have an effect on its sound. I tried a number of cords, including those as different as a Shunyata Taipan, which sounds very fast and lively, to an Essential Sound Products The Essence, which sounds rich and dark. Only with these two extremes did I detect any sonic differences, and then only very slight ones — if any at all. I also used the stock power cord that comes with the No.32 for an extended period, and liked the sound of it as well as that of any after-market cord I tried. The verdict: Experiment, but don’t ignore the null option and overlook the power cord that comes with the No.32.

Preconceived misconceptions

I’ve owned a lot of audio equipment over the years, but no solid-state preamps. I like the idea of having no tube-related maintenance, but the overall sound quality of the solid-state preamps I’ve heard has never equaled that of the best preamps that use tubes. The air, the sweetness, the midrange magic of a good tubed preamp are all undeniable. In many ways, the tubed preamps available today are like moving-coil phono cartridges: They are for those listeners who want the very best sound, are willing to pay a premium for it, and can deal with any added considerations involved.

The No.32 Reference, however, altered this notion. I won’t say that its sound was tubey, but it was apparent from the first few moments of listening that the No.32 was in a sonic league of its own among solid-state preamps, at least the ones that I’ve heard. Its sound is best summed up as silky, with such ease does it portray music, conveying all manner of relevant detail in an utterly agreeable, unrestrained manner. The first few hours of listening took a bit of adjustment — not in terms of my ears, but rather my head. I had simply never heard a solid-state preamp sound as good as, or similar to, the No.32.

As often happens when a musically significant piece of audio equipment comes into my system, I reach for a number of staple recordings so I can get a better idea of what that component is really doing. Keith Richards’ Main Offender [Virgin 864992] was raucous and spacious at very loud levels, while the Rolling Stone’s Let it Bleed on hybrid SACD [Abkco 90042] retained its hear-into-the-master-tape quality, and even sounded a touch sweeter than usual. Bass on “Words of Wonder” from Main Offender sounded warm and fuzzy — exactly as it should — while the pounding kickdrum from “Runnin’ Too Deep” had impressive speed, heft and impact. I listened at louder-than-normal levels as this music begged for a heavy hand on the volume control. The No.32 untangled all of the instrumental lines, its performance never congealing or sounding stark or overly crisp — quite the opposite, in fact.

At CES I talked with Winston Ma, the man behind the First Impression Music audiophile recording label, about the various formats in which FIM releases recordings. FIM recordings are created with extreme sonic care and have been released in HDCD, gold CD, XRCD, XRCD2, XRCD24 and SACD formats. Of course, this begs the question, “Which is the best-sounding format?” I asked Winston this, and his answer didn’t completely surprise me: “XRCD24 is best for sound.” I had been listening to two recent XRCD24s whose sonics were extraordinary: Portrait of Bill Evans [Victor VICJ 61171], a tribute compilation to pianist Bill Evans; and Manhattan in Blue [Victor VICJ 61172], a live-to-two-track recording by alto saxophonist Malta. Both of these carefully wrought CDs sound immediate and have huge soundstages that will tax the resolving power of any audio component. The No.32 handily conveyed all of the startling detail on both CDs and resolved the soundstage’s impressive lateral spread. Piano on the Evans tribute was rendered well in terms of its size — it filled the space between the big Wilson Audio MAXX 2s completely.

All of this initial listening was done with the No.32 fronting the 110W Lamm M1.2 Reference hybrid monoblocks, not the 18W ML2.1 SET amps, which I listen to most of the time. The No.32/M1.2 combination conveyed passion and intimacy as well as grandeur and authority. Maybe the best feature of the various Paul Simon Warner Bros. remastered CDs is the inclusion of demo acoustic versions of some of the songs, which present them in a completely different light. On Hearts and Bones [Warner Bros. R2 78903] Simon does “Rene and Georgette Magritte with Their Dog After the War” on acoustic guitar, and it’s wonderfully personal and touching. The No.32 placed Simon, and indeed the entire soundstage, behind the plane of the speakers — its performance was the antithesis of forward or assertive. The music had grace and flow instead of aggression and edge, and this more than anything came to characterize the No.32’s sound in my system.

Yet, as time went by, I began to wonder if the No.32’s easy-going nature may be an impediment for some listeners, as it kept the music somewhat at arm’s length. Increasing the volume would lessen this, but the view of the music with the No.32 was always from a few rows farther back than I was used to. I have grown to love Ani DiFranco’s Evolve [Righteous Babe RBR-030D] for its jazzy, funky playing and the profundity of a few of the songs. Through the No.32, “In the Way” sounded more gentle and subdued than I was used to, even at loud levels, and the title cut, which I used as a demo at CES and heard on roughly two-dozen different systems, lacked some of the thrust and bounce I had grown to enjoy.

This tendency was exacerbated when I began using the No.32 with the Lamm ML2.1 mono amps. The amps didn’t lack for power, but the sonic signatures of the preamp and amps were not presenting a musical picture that included raucous immediacy as well as ease — and everything in between. In fairness, the No.32 was created with powerhouse solid-state amplifiers like those from Mark Levinson in mind. With the hybrid Lamm M1.2 amps, the No.32’s performance was satisfying and complete; with the ML2.1s, however, the sound was contoured, soft, and not to my liking.

Reference vs. Reference

The Lamm Industries L2 ($14,390) is similar to the No.32 in that it is a two-box unit that its maker has named its Reference preamp. However, the similarities end there. The L2 is a hybrid unit, with a solid-state line stage and a tube-rectified power supply. It has no remote control (“bad for sound,” says Vladimir Lamm) and no balanced inputs (there is a pair of balanced outputs, but the L2 Reference is not fully balanced itself). It’s not as conspicuous as the No.32 in its features or looks, but it is still one of the very best preamps I have used and a unit you should seek out if you’re considering the No.32. Heck, when you’re about to spend in excess of $15,000 on a stereo preamp, you should hear the L2 and all others in the same price range.

I reviewed the L2 almost four years ago, and owned one for over three years. What it lacked in user-friendly features it made up for with its sonic performance, which was stunning. The L2 made for an instructive comparison to the Mark Levinson No.32.

In my review, I described the L2’s sound as “like [that of] a detailed and exceedingly smooth solid-state preamp with a touch of tube ease and romanticism.” Had I heard the No.32 before my review, I would likely have modified this description. The L2 sounded more forward than the No.32, though not forward intrinsically. Its treble had a bit more vitality and sparkle than that of the No.32, while its midrange was every bit as unadorned and transparent as the No.32’s — not at all warm or tubey. The L2’s bass is well integrated into the music it makes, not overly prominent in any way. This would apply to the low frequencies of the No.32 as well, but the No.32’s bass does have more weight and impact.

The biggest difference between these two top-flight preamps is, therefore, in perspective — with the No.32 putting the music a little farther away than the L2. The L2 is closer to absolute neutral in this regard — it has less of a viewpoint of its own. Other sonic differences are negligible, and would be less likely to sway a potential buyer one way or the other. In terms of usability, there is no contest: the No.32 wins easily.

More is more

The Mark Levinson No.32 Reference may have a feature set suggestive of a home-theater preamp/processor, but it is a purist two-channel affair through and through. Its design is inspired and its execution heroic, it is delightful to use, and, most importantly, it is sonically competitive with the best tube preamps available, offering a perspective different from some of the competition. Even at the No.32’s lofty price, it’s not hard to understand how the money was spent in its manufacture — it regenerates its own power for crying out loud! However, if you want its functionality at a lower price point, Mark Levinson has other preamps that make use of the No.32 design innovations and cost less.

All of the No.32’s features make it a useful tool for audio reviewers, but I don’t mean to limit it to such utility. The Mark Levinson No.32 Reference is a connoisseur’s preamp — a fully equipped hybrid sedan with the heart of a zippy, agile sports car. That it’s just plain fun to drive is a considerable bonus.