NAD M51 Direct Digital D/A converter

Original price was: R58,000.00.R22,000.00Current price is: R22,000.00.

NAD M51 Direct Digital D/A converter

The honey badger of DACs?

Then there’s that attitude: The NAD resamples everything you throw in its direction and converts it to a pulse-width-modulation (PWM) signal, the native format for DSD, at a sampling rate of 844kHz, all controlled by a clock running at 108MHz. It doesn’t care if you want this done or not—it just does it. This is done within a 35-bit architecture using a similar PCM-to-PWM approach as the company’s M2 integrated amplifier, which John Atkinson favorably reviewed in the March 2010 issue.

So is this in-your-face hi-rez arrogance, or bitstream brilliance for $2000?

NAD claims a key advantage of their approach: that it eliminates jitter at the conversion stage, and that the subsequent digital filters exhibit zero ringing. I’ll leave it to JA to confirm those claims with his test gear, while I use my ears and brain to hear what happens when you slice and dice a lowly PCM input signal into a million little pieces and send it back out again.

Walkabout

The M51 is an attractive, full-width component with a half-inch-thick aluminum front panel and a minimalist case of medium gray that remained cool to the touch at all times. It’s surprisingly robust and hefty, with little going on out front—and not a lot crammed under its thick metal hood. At the left of the front panel is the Standby off/on button, at the right an identical button to select inputs. In between is a rather wide blue-letter vacuum-fluorescent display (with adjustable brightness!) that you can read from across the room; this indicates input, volume status, and sampling rate. That last benefit is one that I wish more DACs had—it comes in handy when you need to verify that, yes, the USB driver is sending the right resolution through the cable, or that the file on your server that you forgot to label is in fact 88.2kHz.

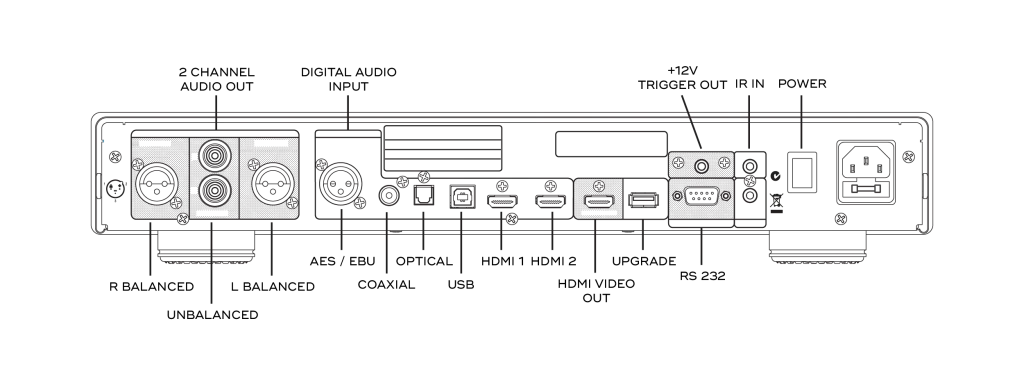

At the left of the rear panel are high-quality analog outputs, balanced and unbalanced; at the right, a socket for the detachable AC power cord and a power switch. In between are AES/EBU, coaxial, optical, USB, and two HDMI inputs. To the right of those is an HDMI output, which is simply a direct pass-through of only the signals from the HDMI inputs—handy for looping your Blu-ray player into the system to extract two-channel audio while sending the video along. To the right of that is a USB jack labeled Upgrade, strictly for updating the M51 via thumb drive. Then come some automation jacks: RS-232, 12V trigger in, IR in. All inputs can handle PCM audio data of resolutions up to 24-bit/192kHz.

The sturdy remote control is festooned with buttons and is essential for setup and volume control, dimming the front panel, and switching polarity. It also has buttons for NAD transport and CD-player functions, and makes it easy to directly select inputs via the M51.

Attitude adjustment

I unplugged my reference Benchmark DAC1 USB D/A converter and set up the NAD M51 with my usual intention: I’d run it for several weeks as my main D/A converter, getting familiar with its sound and operation, and then do some serious comparisons. I wasn’t sure how I felt about this new PWM-conversion thing entering my PCM domain, and wanted time to assimilate into the house this new digital stranger.

The M51’s digital volume control lets you run it as a preamp directly into a power amp and control your system volume with NAD’s remote. Because of the HDMI inputs and output, you could even use it as a limited two-channel audio/video preamp, though I didn’t try that. The only drawback I could see using the NAD as a preamp is that there are no volume buttons on the M51 itself; you’d have to decide where to put the remote and leave it there. If you lose it, you’re screwed.

The M51’s volume-control technology is impressive, though. According to NAD, “The extreme headroom afforded by the 35-bit architecture allows for a DSP-based volume control that does not reduce resolution. Even with 24-bit high definition signals, the output can be attenuated by 66dB (very, very quiet) before bit truncation begins.”

What was weird was that, while setting levels, as I switched back and forth between DACs with the pink noise running, there was a slight difference in the character of the sound. After I’d adjusted the NAD’s volume trim, the SPL meter read “0dB” for each DAC, but something subtler was going on—the tonal quality of the pink noise shifted just a little in the room. Later, I figured out what this meant musically.

All My Lovely Goners, the latest release from Winterpills, is a great Americana record (CD, Signature Sounds SIG 2044): folky, rocky pop that strikes me as the kind of album I wish Neil Young would get down to business and make—you know, with catchy tunes and harmonies. In this world of accolades for Fleet Foxes and Bon Iver, I wonder why Winterpills isn’t getting more notice.

Anyway, listening to the first couple tracks through the NAD revealed the music’s wholesome and well-appointed arrangements, which rock out in places but also sport acoustic guitars and harmonies galore. This isn’t a demo-grade recording—the sound is somewhat confused and brassy when things get complicated—but via the NAD it was thoroughly enjoyable and never grated. The M51 projected a rich, lovely sound that wasn’t too forgiving, which was to its credit. I like to hear a recording’s technical warts, if any.

Next up was Nils Petter Molvær’s Baboon Moon (CD, Thirsty Ear 57201). There’s a lot going on here, with Molvær’s wandering, plaintive trumpet set against a dark, churning background. Here is where the NAD’s ability to handle rumbling bass and spatial character revealed a taut and capable DAC. But this album is a torture chamber of tangled bass, and I sensed a very slight thickening compared to the Benchmark. Or perhaps the Benchmark was a touch too thin . . . ?

Exploring this further, I compared the NAD to Ayre Acoustics’ QB-9 DAC via both models’ asynchronous USB inputs, using my Apple laptop running iTunes and Amarra. I cued up Nick Lowe’s brilliant sophomore album, Labour of Lust (CD, Yep Roc YEP-2621), and cranked through the first four songs several times, occasionally tossing in the Benchmark. The NAD had all the inner detail of its venerable rivals, which many lesser DACs lack. All the musical detail was there, and it sounded as if there were more meat on the musical bones than with the Benchmark—though the NAD lacked just a nanotad of the Ayre’s punch and square dynamic edges. The Benchmark sounded more like the Ayre in this regard, but overall wasn’t as finessed and musically pleasing as the NAD. I would still choose the Ayre if USB were all I needed, but the NAD didn’t embarrass itself; in fact, it impressed me, especially in light of its features and lower price.

I also ran my iPad as a digital streaming source, using the clever USB adapter trick that Michael Lavorgna details at www.audiostream.com. No problems running it straight into the M51’s USB input and playing a CD rip—Roxy Music’s For Your Pleasure (Reprise 26040)—that I’d transferred to the iPad at full resolution. Interestingly, this trick works with the Benchmark too, but not with the Ayre. I tried everything, but could never get the iPad to play through the QB-9’s USB jack.

HDMI benefits and limitations

Finally, I connected the HDMI output of my Oppo BDP-83 universal Blu-ray player to the HDMI input on the back of the NAD and popped in a DVD-Audio disc. Because I’d already ripped this disc to the Sooloos as 24/96 files, this seemed a great time to compare the NAD’s inputs. I cued up the Doors’ L.A. Woman (DVD-A, Elektra 755975011-2) on both the Oppo and the Sooloos and, using the NAD’s remote, switched back and forth in real time.

The M51’s HDMI input is stereo only; comparing the Sooloos via S/PDIF to the Oppo via HDMI, I heard, right off the bat, a big difference in volume level between the two feeds. After a bit of testing and more pink noise, I found that the Oppo-NAD HDMI combination was a full 8–9dB lower in level, according to the NAD’s readout. Once this was sorted out, it was a bit of a pain to go back and forth between the two sources, adjusting the NAD’s volume each time, since I couldn’t trim each input. But after doing just that several times, it was apparent that Oppo vs Sooloos was as close to a tie as I could hear. The NAD’s display reported that the Sooloos was sending the correct 96kHz stream across, and the HDMI from the Oppo was also running at 96kHz.

I played a Neil Young DVD-A in the Oppo via HDMI, and the NAD M51 displayed the correct 176.4kHz sampling rate. I then grabbed an SACD of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells and popped it in the Oppo. Uh-oh. This time the M51’s display read 88.2kHz—clearly, an SACD stream fed to the M51’s HDMI input will be downsampled to PCM. NAD has confirmed that the M51 can’t accept DSD audio via HDMI, but can accept SACD playback if converted by the BD/SACD player at up to 24/192 PCM.

Morten Lindberg, from Norway’s 2L label, had recently sent a bagful of music-only recordings on Blu-ray that contained two-channel, high-resolution PCM tracks along with surround-sound versions in various configurations. I put the 2L sampler in the Oppo and once again hooked up via HDMI. The NAD’s display jumped to 192kHz. Over the next few nights I played several of the 2L discs, even transferred some of the included 24/96 FLAC files to the Sooloos, and bathed in the glorious detail coming out of the speakers. Kal Rubinson and John Marks have been singing the praises of Blu-ray audio for months, but this was the first music-only BD I’d run in my system this way. I now understand what all the fuss is about.

Conclusions

I admit to having been a little suspicious at first of the PCM-to-PWM approach that NAD has taken in the M51. That was before I’d had a chance to live with it for a couple months. Nothing raised an eyebrow, and the claimed benefits in jitter rejection and filter design have obviously paid off.

I prefer DACs that reveal as much as possible about what was captured on the tape or in the digits, and couldn’t care less about adding a rose-colored tint to dodgy digital sound. In this regard, the NAD M51 succeeds with a wonderfully detailed and revealing sound best described as honest, with a friendly smile. And it was a pleasure to listen to.

In other words, bitstream brilliance.

And, in fact, I found running the M51 via its variable volume control sounded indistinguishable from its Fixed volume mode, and transparent at all practical levels. To compare the NAD with my other DACs without having to worry about the level changing by mistake, I set it up in the Fixed volume mode and ran the outputs into my Marantz AV7005 preamp. The NAD lets you trim its Fixed output, so I set it to “0dB,” assuming this would match the output level of my other DACs. The remote’s Mute button still works in this mode, but the volume up/down buttons are disabled.

Figuring that all was well, I ran some music from the Meridian Sooloos Control 15 (footnote 1) via the coax input and noticed right away that instruments jumped out at me a bit more than I was used to at my standard preamp volume setting. Wow, this DAC was sounding different already! I plugged the Benchmark DAC1 back in and the level sounded more normal. I then got out my RadioShack SPL meter and ran pink noise from Test CD 2 (Stereophile STPH004-2) through the system. Sure enough, the NAD, set at “0dB,” measured 1–2dB louder than the Benchmark at my listening position. (JA can check this in his tests.) I reduced the Fixed level by 1dB and all sounded normal again.

And hearing the DAC in action, it’s hard to argue otherwise. Music sounds wonderfully clear and transparent. 50 Cent’s In Da Club is powerful and robust, with the solid-sounding bassline acting as a rigid backbone.

The Manic Street Preachers’ Motorcycle Emptiness sounds engaging and communicative with an excellent sense of precision to the drums and a crisp, natural tone to the guitar melodies.

The M51 can reproduce detail and sonic textures cheaper DACs struggle to convey, and this is as true when listening to 16-bit/44.1kHz CD playback as it is when indulging in a 24-bit/192kHz high-res file.

NAD M51: Tech specs

The inclusion of dual HDMI inputs and a single output is unusual, but it means the M51 can strip the two-channel PCM audio off the signal from a Blu-ray player and pass the picture through, or take a high bitrate feed from a DVD-A or SACD disc.

You’re limited to a 2.0 speaker set-up, but this feature is aimed more at the two-channel purist.

Build quality is decent for the money: the front panel looks and feels solid enough but the rest of the chassis feels slightly ‘tinny’.

NAD M51: Verdict

The M51 sounds sensational. In fact, we’d go further than that by saying it’s one of the best NAD separates we’ve heard in recent memory.

- Details

- Written by S. Andrea Sundaram

- Category: Full-Length Equipment Reviews

- Created: 15 December 2012

NAD Electronics began 40 years ago with what was then a different business model from that employed by their hi-fi competitors. The electronics were designed in England, but manufacturing was farmed out to firms in Taiwan with lower labor costs — a model that is now the norm in the audio industry. NAD quickly developed a reputation for good performance and strong value that they’ve maintained in the decades since then. Today, NAD’s product development is a collaboration between engineers in Canada, England, and Hong Kong, with manufacturing in mainland China. Although NAD is still committed to offering a variety of products at modest prices, a few years ago they decided to take their engineering, build quality, and pricing more upscale, and launched the Masters Series components. With these models, they hope to retain their loyal customers as their ambitions grow, and perhaps attract some new ones who may not have been considering the brand.

NAD Electronics began 40 years ago with what was then a different business model from that employed by their hi-fi competitors. The electronics were designed in England, but manufacturing was farmed out to firms in Taiwan with lower labor costs — a model that is now the norm in the audio industry. NAD quickly developed a reputation for good performance and strong value that they’ve maintained in the decades since then. Today, NAD’s product development is a collaboration between engineers in Canada, England, and Hong Kong, with manufacturing in mainland China. Although NAD is still committed to offering a variety of products at modest prices, a few years ago they decided to take their engineering, build quality, and pricing more upscale, and launched the Masters Series components. With these models, they hope to retain their loyal customers as their ambitions grow, and perhaps attract some new ones who may not have been considering the brand.

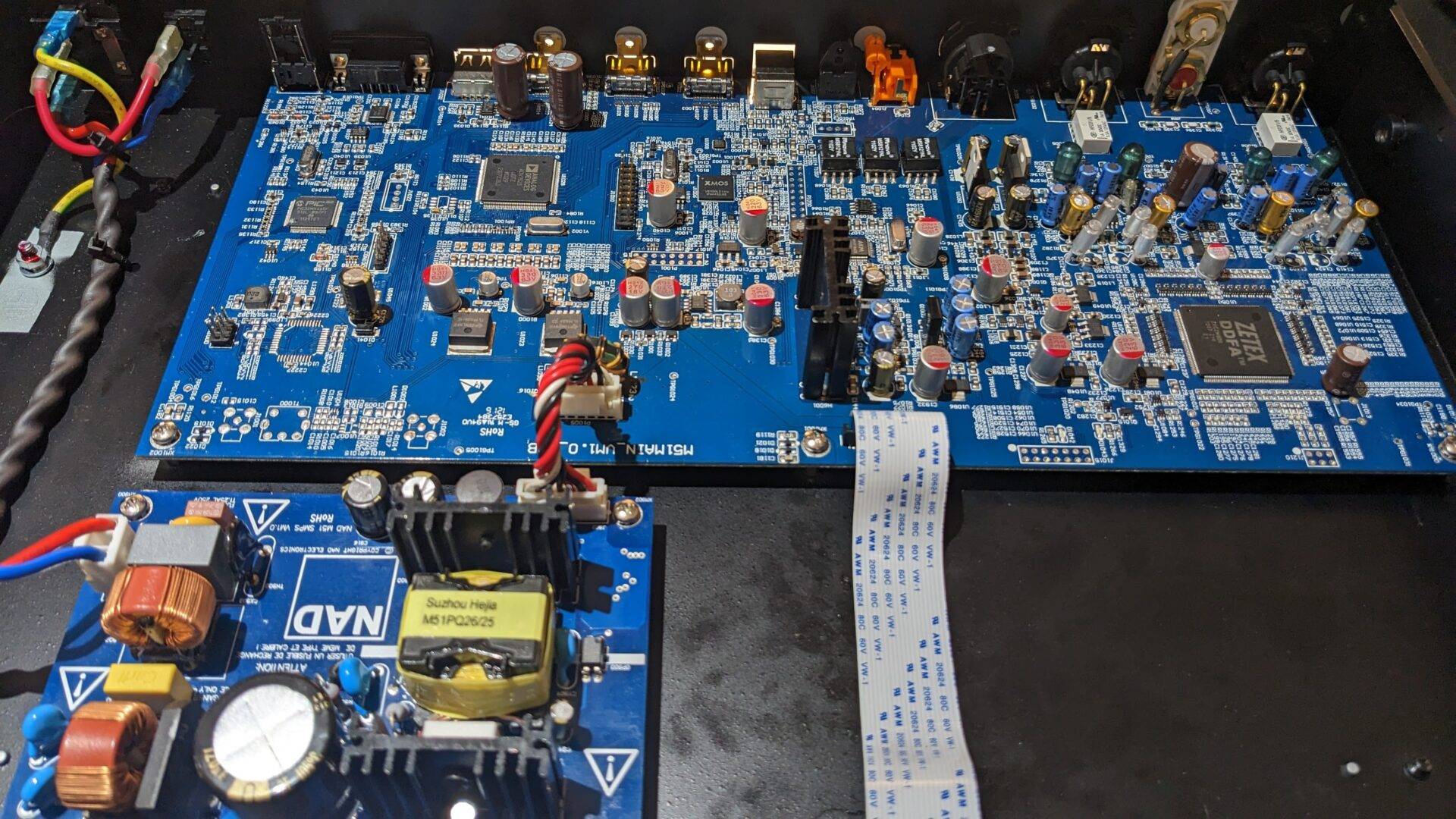

The Masters M51 Direct Digital digital-to-analog converter ($1999 USD) is based on the same CSR Direct Digital Feedback Amplifier chip used in the Masters M2 Direct Digital integrated amplifier. Rather than the pulse-width modulated (PWM) bitstream switching 50V rails, as in the M2, the CSR chip is coupled to an output stage that delivers 4.75V RMS to the balanced outputs and 2.375V to the single-ended. All incoming PCM data is converted to a 7-bit/844kHz PWM signal, with mathematical operations carried out to 35-bit precision. The PCM-to-PWM conversion and the width of the pulses are controlled by a master clock running at 108MHz. The analog output is compared with a reference PWM signal, and any corrections are made in the digital domain. (This correction loop is why it is called a Direct Digital Feedback Amplifier.)

The M51 is a full-size component measuring approximately 17″W x 3″H x 12″D and weighing just shy of 13 pounds. The case is primarily stamped steel, with a dark-gray powder coat and a faceplate of 3/4″-thick aluminum milled to curve back toward the sides. The look and feel are of quality but not opulence. The front panel’s central display gives the input, incoming sample rate, and volume setting. The only controls are a power/standby button and a button that cycles through the available sources. Direct source selection, signal polarity, and volume control are available only from the remote control. Around back is a bevy of connectors: AES/EBU, coaxial, and optical digital inputs, an asynchronous USB input, and the standard IEC power inlet. All inputs accept sample rates up to 192kHz. (Windows users must download an ASIO driver from NAD’s website for the USB input to support sample rates above 96kHz.) The M51’s most unusual feature is the presence of two HDMI inputs, so that it can accept uncompressed stereo audio data from a Blu-ray player or other device. (Multichannel audio is not supported.) There is also an HDMI output that allows video signals to pass through the M51. (NAD suggests that the M51 could be used for a high-quality, two-channel home-theater setup.) There are 12V in and out triggers and an RS-232 port for system integration, along with another USB connection for firmware updates. Analog outputs are available on both XLR and RCA connections.

The presence of a digital volume control suggests that you run the M51 directly into your power amplifier. Since the volume control operates in the 35-bit domain, no bit truncation will occur with 24-bit sources until you reach 66dB of attenuation — really, really quiet. Greg Stidsen, NAD’s director of technology, advises those using the M51 as a source into a typical preamplifier or integrated amp to set the volume control to -1dB rather than 0dB, as that level has better distortion performance. The measured output of this volume setting for a full-scale sinewave — a shade over 4.2V balanced and 2.1V unbalanced — was also very close to that of my reference CD player, the Ayre Acoustics C-5xeMP universal two-channel disc player.

For this review, I ran the NAD’s balanced outputs into my Graaf GM-50 integrated amplifier, and also listened with the M51’s single-ended outputs run into my Woo Audio GES electrostatic headphone amplifier. CD data were fed to the NAD via an AES connection from the Ayre. Higher-resolution data came over USB from my laptop running Windows Vista and, alternately, foobar2000 and JRiver Media Center. I also tried a few ripped CDs to compare the AES and USB performance, but heard no significant difference.

Sound

One of the challenges in reviewing DACs is that so many of them sound so similar to each other. That may be, at least in part, because most of them are based on a relatively small number of DAC chips. Whether it was due to the Zetex chip at its heart or some other aspect of its design, the Masters M51 had a character different from that of other DACs of my recent experience. It sounded relaxed, soft, and, tonally, a little on the warm side of strict neutrality. The M51’s sound was the antithesis of the hard, brittle, edgy qualities that some audiophiles have ascribed to digital over the past three decades.

This forgiving disposition took the sting out of early tape-to-digital transfers — such as the 1990 version of Sade’s Diamond Life (CD, Portrait RK 39581). Many of today’s mainstream pop releases also benefit from a little tempering. Adele’s voice in “Rolling in the Deep,” from her 21 (16/44.1 FLAC, XL Records), retained the searing quality that’s part of the song’s style, but the tambourine had less bite and the cymbals less sizzle than usual. It’s not that the M51 turned these far-from-perfect recordings into sonic spectaculars; it just made their flaws less obvious and irritating. Carlos Santana and John McLaughlin’s Love Devotion Surrender (CD, Columbia CK 63593) isn’t ruthlessly compressed or a particularly bad transfer, but I usually find it a little fatiguing when I play it at levels appropriate for this type of music — i.e., room-fillingly loud. Again, the NAD let me listen through the entire album without strain.

There was, however, a downside to this easygoing nature. Mark Walker’s hi-hat work in “The Peanut Vendor,” from Paquito d’Rivera’s Portraits of Cuba (24/96 FLAC, Chesky/HDtracks), was a little hazy where I know it can sound more realistically metallic. Although I appreciated being able to listen to the Santana-McLaughlin album without a headache, the M51’s rendition lacked some of the drive and energy I want from rock music. Classical music, too, often benefits from a more exacting sound. When I listened to pianist Ronald Brautigam’s recording of Mozart’s Piano Concertos Nos. 17 and 26, with Michael Alexander Willens leading the Cologne Academy (24/96 FLAC, BIS/eclassical), the NAD’s relaxed delivery made the ensemble’s playing seem a little loose and inattentive.

Some music is meant to sound relaxed. Eva Cassidy’s charming and intimate Simply Eva (CD, Blix Street G2-10099) suffered not at all; the M51 communicated her phrasing with great fluidity, painting both voice and guitar in warm, mellow tones. The NAD also captured the easy sense of swing in the Oscar Peterson Trio’s Night Train (24/96 FLAC, Verve/HDtracks). Ray Brown’s bass exhibited a little more bloom than I’m accustomed to hearing, but individual notes never blended into each other.

Speaking of bass . . . the M51 delivered substantial weight and body with lower-register instruments — whether acoustic or electric bass, or tuba and contrabassoon in Kalevi Aho’s concertos for each of the latter, as respectively performed by soloist Øystein Baadsvik with Mats Rondin conducting the Norrköping Symphony Orchestra; and by soloist Lewis Lipnick with Andrew Litton conducting the Bergen Philharmonic (CD, BIS 1574). Moving even further down the audioband, the NAD made orchestral bass drums sound big, and provided the necessary foundation to the organ in Jan Lehtola’s recording of Aho’s Symphony for Organ (24/96 FLAC, BIS/eclassical). Some other DACs give a firmer attack to bass notes, but the M51 didn’t really lack in this regard. Through it, the kickdrum on Adele’s “Rolling in the Deep” left no doubt as to where the beat lay, and drummer Bernard Purdie’s kickdrum accents on Bucky Pizzarelli’s Swing Live (24/96 FLAC, Chesky/HDtracks) really popped.

Finally, the M51 was capable of throwing a soundstage that extended past my speakers to the left and right. The placement of instruments and voices along that continuum was stable and well defined. Those images began just behind the speaker plane, but with little variation in depth. With the Mozart album, Brautigam’s piano was squashed in among the orchestra. With the greater space captured on Ole Bull’s Concerto Fantastico (24/192 FLAC, 2L/2L), the M51 layered the solo violin in front of the orchestral strings, which were in front of the brass, but these distinctions were not great and any sense of hall ambience was lost. When these positional cues are on a recording, I feel it is the responsibility of a high-end DAC not to obscure them. If, on the other hand, you primarily listen to studio recordings that lack a multidimensional soundstage, this criticism of the M51’s performance may not be terribly relevant.

Comparisons

Earlier this year, I reviewed the Resonessence Labs Invicta DAC ($3995), based on the Sabre 9018 from ESS Technologies and designed by some of the people who worked on that chip. The Invicta doesn’t support audio over HDMI (that capability may be added in future firmware), but it has a number of other features the M51 lacks. The Invicta’s two headphone outputs are of very high quality, and their volume levels can be independently controlled. The Resonessence also has an SD card slot that allows for direct playback of music stored in the WAV and AIFF formats, with some minimal capacity for navigating the card’s contents. The Invicta’s casework is assembled from precision-machined pieces of anodized aluminum that fit together with such close tolerances that the component almost seems as if hewn from a single block. The rear-panel inputs and outputs are of extremely high quality, and each is galvanically isolated from the chassis. Similar attention was given to the internal circuit layout, and the Invicta is powered by a customized toroidal transformer. There’s nothing wrong with the look or feel of the NAD, but the Resonessence is built to a higher standard. Its additional features and superior build quality may or may not matter to you, but they go a long way toward justifying its higher price.

The Invicta offers the choice of two digital reconstruction filters, but I’ll concentrate this comparison on the slow-rolloff option, which I generally found more compelling. With this filter, the Invicta created a holographic soundstage that extended far outside my speakers and possessed a staggering degree of depth. Each sound source was precisely placed within that space, and the reverberation trails around everything, from a single plucked string to a dense piano chord to a larger collection of instruments or voices, placed those sources within a distinct acoustic environment — when one had been captured on the recording in the first place. The Invicta’s bass was extended, with great control and impact that supported the greater sense of space and made for a more visceral listening experience than with the M51. Though there was no obvious rolloff in the highest frequencies, the overall balance was a bit dark. (It was dead neutral with the fast-rolloff setting.)

In describing the Invicta’s sound in my review, I used the words smooth and relaxed; I also said it was forgiving of poor recordings. I would still characterize the Invicta that way, but it’s none of those things to the extent that the NAD M51 was. The Invicta’s high frequencies are more refined than those of the M51, giving a more complete picture of each instrument’s harmonic structure and better clarity to things like cymbals and triangles. On the other hand, the NAD’s softer highs will make even the most overcooked albums sound inoffensive. There was a difference to their smoothness through the midband as well. Listening to Willie Nelson and Wynton Marsalis’s Two Men with the Blues (CD, EMI 5 04454 2), I noted in my review of the Invicta that Nelson’s voice “was slightly muted by the Invicta’s Slow filter, as if Nelson had taken a step back from the microphone or was coming down with a slight cold.” The NAD placed his voice more upfront with all of its twang, but left out some of its texture. Though the M51 was good at uncovering the incidental sounds that often make it onto recordings, the Invicta was a little better. Finally, I noted a slightly damped character in the Invicta’s reproduction of transients — it made pianos, for example, sound a bit less lively than they should. Transients through the M51 were a little rounded, but still felt less constrained. Although I can imagine some listeners preferring the NAD’s warmer, extra-relaxed sound, overall, the nod for higher fidelity goes to the more expensive Invicta.

I usually extract digital data from my computer by connecting its coaxial digital output to my Grace Design m902 DAC/headphone amplifier. The m902’s USB input is limited to 48kHz and is highly prone to jitter, but the current model, the m903 ($1895), includes an asynchronous USB input that accepts sample rates up to 192kHz. Like the Invicta, the m902 has many more features than the M51, including an excellent headphone amplifier and two analog inputs, but no HDMI.

Like the NAD, the Grace is also a little warm through the midbass and midrange, but its high frequencies are less forgiving. On the downside, if a recording is edgy in the highs, the m902 will treat it less kindly than the M51. With properly recorded and mastered material, the m902 generally does a better job of rendering instruments’ upper harmonics. With standard-resolution sources, those more revealing highs could cut both ways. On the Marsalis-Nelson CD, when Marsalis’s trumpet shouts into the microphone, the m902 reproduces its overtones more realistically — but, after all, it’s a sound that’s rather in-your-face. The M51 took a more subdued approach that traded vibrancy for comfort.

Through the Grace, the triangle in the second movement of Mahler’s Symphony No.3, with the Chicago Symphony under Bernard Haitink (CD, CSO Resound CSOR 901) — as well as the triangle in the recordings of Dvorák’s Cello Concerto and Slavonic Dances with Adrian Leaper and the Gran Canaria Philharmonic Orchestra (CD, Arte Nova 74321 34054 2) — rang out more cleanly above the orchestra, but with the stunted quality that has been common among DACs over the past decade. The NAD forwent that artificiality, but didn’t allow the sound to float free of its surroundings as it does in real life. It took players like the Resonessence Labs Invicta and the Ayre C-5xeMP to make that shimmering quality sound natural. As I moved to recordings made at higher sample rates, the m902 rewarded me with even greater verisimilitude; but whether I played high-resolution files or those from standard “Red Book” CDs, the M51 sounded pretty much the same.

Though I don’t think the Grace’s bass extends any deeper than the NAD’s, it’s better defined. That means a more forceful attack for kick drums, and a better separation of the sound of bass instruments from their surrounding acoustic environments. The latter may have been, at least in part, responsible for the Grace’s better rendering of recorded ambience. The m902’s soundstage wasn’t quite as wide as the M51’s, but it was deeper, with more explicit relationships in the positions of instruments. But while the Grace bested the NAD in this regard, it was no match for the Resonessence in the creation of huge, holographic soundscapes.

The M51 was very smooth and fluid in its presentation, the m902 crisper and more precise. Not only was the piano in the Mozart recording better separated, spatially, from the orchestra, but the ensemble sounded more deliberate in their performance — which made the music more interesting. In Brautigam’s recording of Mendelssohn’s Lieder ohne Worte (24/96 FLAC, BIS/eclassical), the solo piano had much more percussive attack in the faster songs through the Grace, and a more realistic sound of hammers hitting strings, than the rounder-sounding NAD. Jazz recordings were a little snappier, and rock had a little more drive. The trade-off for all of this precision is that the Grace can sometimes sound a touch mechanical — the NAD never did. The m902 delivers more of what’s on the recording, but I know that some listeners will prefer the more laid-back sound of the M51.

Conclusions

The DAC market is a crowded place. To make any headway, a new entrant — even one from a thoroughly established brand like NAD — needs to offer something special. Feature-wise, the Masters M51 matches its competition, and ups the ante with those two HDMI inputs and its pass-through facility, making it the only high-end DAC of which I’m aware that really fits in the two-channel home-theater space. It looks at home with other modern hi-fi components, and, of course, it’s the perfect match to NAD’s forthcoming Masters M50 digital music player and Masters M52 storage vault.

The M51’s sound, too, is something a bit different. Other DACs take a tighter hold on the music, tease out more detail, or create a better-defined soundstage. What the Masters M51 offers is a sound that’s smooth, laid-back, and always pleasant, no matter what you throw at it. Its slight favoring of the midrange imbues the sound with just a hint of extra warmth. For many listeners, such a combination is a recipe for audio bliss.

Description

Product highlights:

- 35-bit/844kHz up-sampling digital-to-analog converter operating in differential mode for precise sound

- asynchronous USB technology for reduced jitter and better sound with computer-based audio

- front-panel vacuum fluorescent display shows sampling rate to verify source quality

- preamp function with selectable inputs and remote volume control

- 35-bit DSP-based volume control maintains full 24-bit resolution sound

- phase-inversion (polarity) switch to compensate for out-of-phase recordings or phase-inverting amplifiers

- HDMI connections with video pass through to allow two-channel home theater with a Blu-ray or DVD player source

- remote control

Inputs:

- two digital audio inputs: one optical (Toslink) and one RCA coaxial

- USB (Type B) input for connecting a computer

- two HDMI inputs for stereo-only audio and 3D-compatible video pass through

- balanced digital XLR audio (AES/EBU)

Outputs:

- one pair RCA audio

- one pair balanced XLR audio

- one HDMI video

Other info & specs:

- supported sample rates: 32kHz to 192kHz (USB and digital S/PDIF inputs)

- dedicated NAD USB Audio 2.0 Windows driver required for playback on a PC (free USB driver download available from NAD’s website)

- Mac OSX 10.6 or later includes NAD USB Audio driver, so no download is required

- frequency response: 20Hz to 96kHz @ 192kHz sampling rate(±0.5 dB)

- THD: <0.001%

- signal-to-noise ratio: less than -123 dB

- channel separation: greater than 115 dB

- output level: 2V

- RS-232 port for automated control systems

- 12-volt trigger and IR input

- detachable power cord

- 17-1/8″W x 3″H x 13-1/16″D

- weight: 12.8 lbs.

- warranty: 3 years