Brinkmann Marconi MKII Preamplifier (RARE)

Original price was: R260,000.00.R140,000.00Current price is: R140,000.00.

In New York, over a decade ago, I first came across the Brinkmann Balanced turntable. It was hooked up to a tube power supply—an act of dedication that inspired confidence in the company’s mission to extract the very best possible sound from vinyl records. It remains the only turntable I’ve seen that was powered by tubes.

Helmut Brinkmann’s eponymous company is probably best known for its turntable line, but it has produced a variety of front-end equipment for several decades. Now this German company is mounting a fresh effort to make a mark in that sphere with a passel of new products, including its Nyquist DAC Mk II, Edison Mk II phonostage and Marconi Mk II linestage—all of which, incidentally, contain new old stock Telefunken PCF-803 tubes that were originally used in color television sets back in the 1960s. Brinkmann rates them as having a life expectancy of around twenty years. Brinkmann’s gregarious American representative, Anthony Chiarella, dropped off all three of the Brinkmann units at my house and listened to them for an afternoon before leaving them with me for review.

I wasn’t sure what to expect from the Brinkmann gear, but I did know that the company’s emphasis on tubes is very much a good thing. I’ve heard a lot of solid-state equipment in recent years, but have never been fully convinced that it can quite attain the ethereal regions that tubes seem to reach and deliver. There is a certain nuance and alacrity, transparency and silkiness, that tubes offer. Don’t get me wrong: Solid-state keeps getting better almost every day in every way. But as with vinyl, the case for using tubes isn’t going away. If anything, it’s getting stronger.

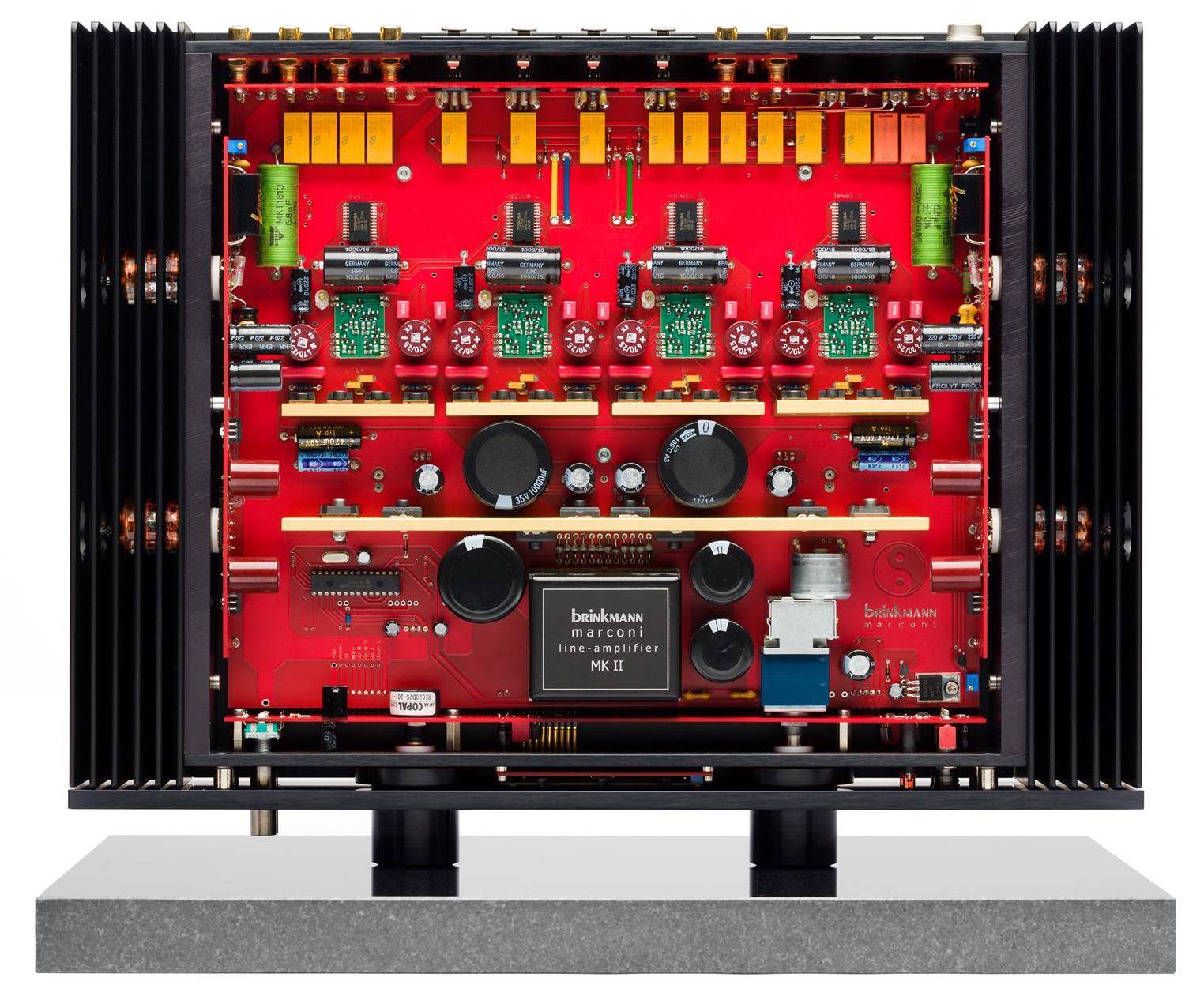

The hybrid Brinkmann equipment is a good case in point. No one would call it inexpensive. But my sense in listening to it was that, in an age when the prices of top-flight equipment appear to be soaring into the stratosphere and beyond, Brinkmann has a lot to offer. It’s seduction in a small package. For the first thing that you’ll notice about these new Brinkmann pieces is that they are sleek and unobtrusive. They convey a certain elegance, plus the glass tops are fun to peer through, allowing a glimpse of the internal parts. They also come with black granite bases that are supposed to function as absorbers of untoward vibrations that can muck up the sound.

All three units run balanced. On its website, Brinkmann claims that “immunity from noise can only be achieved with balanced signal processing.” Hmmm. That would come as news to a variety of other designers. My single-ended Ypsilon gear, for example, runs pretty much dead quiet. You won’t hear any noise emanating from the loudspeaker or, for that matter, from the equipment itself. But there is no question that balanced operation, with its advantage of common-mode rejection, is supposed in theory to offer quieter performance, and I never heard any buzz or hum from the Brinkmann gear. Instead, it was free of noise.

There can be no question that Brinkmann packs a lot into its fetching units. Some of the highlights: Each has its own independent solid-state power supply that is attached to the main unit via a DIN connector. A total of four tubes are side-mounted in over-sized heat sinks and offer what Brinkmann calls virtually “zero voltage delay.” The volume control of the preamp allows you to set each of the six inputs individually. The Nyquist DAC offers a wealth of streaming opportunities so that you can take advantage of the latest and greatest in the digital world, including MQA decoding and PCM up to 384kHz/32 bits (including DXD), as well as DSD64, DSD128, and DSD256—I find, incidentally, that when streaming music I tend to ramble around more musically, whereas with CDs and a fortiori with LPs, I am more focused on the piece at hand. For all its technological wizardry, the Nyquist employs tubes in its output stage. And—drum roll, please—there is also the obverse of digital, the Edison phonostage. It offers continuous gain from 49dB to 73dB, multiple loading settings, and the option of running through a step-up transformer for low-output moving-coil cartridges (or bypassing it), not to mention a mono switch. The ability to play mono records in full fidelity, which I did, is definitely a nice feature, as is the ability to fine-tune the volume setting to your heart’s delight, which I also did via a large knob on the front panel.

Listening kicked off in the digital realm with a variety of CDs and the welcome opportunity to test the Nyquist’s streaming capabilities. On both fronts, the Brinkmann DAC acquitted itself very well, indeed. It was immediately obvious that it errs on the side of a sumptuous and velvety sound. Upholstered, if you will. I ran it and the Brinkmann Marconi Mk II preamp into the Ypsilon Hyperion and D’Agostino Relentless amplifiers, each of which demonstrated different features of this front-end equipment. The Relentless is simply a blockbuster of an amp, allowing you to test dynamics to the limit. The Hyperion likes to probe into the furthest recesses of a panoramic soundstage.

On Leonard Cohen’s final album You Want It Darker, the Nyquist and Marconi created a wide and deep soundstage that allowed you to track each accompanying instrument carefully. The bass was deep, but always carefully delineated.

The dominant impression that the Brinkmann equipment conveyed was of a sumptuous but never bloated sound. Dynamics were superb. On Mavis Staples’ album One True Vine [ANTI-Records], the drums and bass boasted real kick. Throughout, the Brinkmann gear handled the bass region extremely well, revealing nuances that other equipment sometimes skate over. On a Leonard Bernstein recording of Schubert’s Symphony No. 8 with the Vienna Philharmonic, I was bowled over by the texture of the doublebasses at the start of the first movement. Whether listening to solo piano or trumpet, it became obvious that this Teutonic gear wants to woo you, not bludgeon you over the head, with its swagger. Highs were slightly on the darker side, but this helped create a burnished sound.

This came home to me most vividly in listening to the Edison phonostage, which brings us to the heart of the Brinkmann enterprise, namely, vinyl. I listened to the Edison both through the Brinkmann and Ypsilon Silver PST-100 preamps. I found it most useful to isolate its sound by using the familiar Ypsilon. This afforded me the opportunity to hear exactly what it was—and was not—doing as it amplified the tiny signal from my Continuum Caliburn turntable and Swedish Analog Technologies reference CF1 tonearm via the Lyra Atlas SL and Miyajima Infinity mono cartridges.

The phonostage is quite flexible, allowing you to switch the transformers in and out of the circuit to boost the signal from moving-coil cartridges before the amplification stage. On stereo records I found the transformer to be indispensable. On mono records not so much. Many of the mono records from my jazz collection simply sounded incredible on the Brinkmann. Take the album Li’l Ol’ Groovemaker….Basie! The drums were set back far in the rear of the soundstage while the brass choirs came screaming out with what seemed like unprecedented ferocity in my system on cuts like “Nasty Magnus.” Basie apparently told Quincy Jones after the first run-through, “You ought to have written four of these, Quincy! That’s wailin’!” Indeed. Sonny Payne’s drums had visceral impact as the orchestra blasted out a series of crescendos.

Then there was the marvelous 1954 Norgran LP The Artistry of Buddy DeFranco. The interplay between DeFranco and the pianist Sonny Clark, who died in 1963 at the age of 31 and cut a number of solo albums for Blue Note including the classic Cool Struttin’, on songs such as “You Go To My Head” had a visceral palpability to it. The Edison finely rendered Clarke’s assured piano playing while capturing DeFranco’s lambent tone. It was simplicity itself to follow their exchange of musical ideas. The sound was so spectacular that it prompted me to whip out a bunch of other mono albums. It’s always salutary to return to mono records, which have their own weighty sound that can often elude later, supposedly superior stereo recordings. I’ve found that this is so particularly in the bass region. I thus much enjoyed listening to Red Garland’s Prestige album All Kinds of Weather, which features the legendary Paul Chambers on bass. The Edison provided a rock-solid rendition of this trio, the best I’ve hitherto heard.

In waxing eloquent over mono recordings that I’ve accumulated over the years, I hardly mean to scant stereo. The sheer artistry that the Edison conveyed on the Philips recording The Delectable Elly Ameling was a combination of the sublime and the beautiful. On Mozart’s wonderful motet Exsultate, Jubilate, which he composed in 1773, the Edison tracked every syllable, every quaver, every trill that Ameling enunciated during her ravishing performance. It nailed the antiphonal effects between Ameling and the oboe as she sang “Hallelujah.” Once more, there wasn’t a trace of sibilance or harshness. Instead, the Brinkmann delivered a posh, upholstered sound that was quite delectable. Actually, I should say breathtaking. On the Bach “Floesst, mein Heiland, floesst dein Namen,” the interchanges between Ameling, two oboes, and chorus reach an exalted level. Listening to such works made me think of the eighteenth century German writer Friedrich Schiller’s famous distinction between naïve and sentimental poetry—the former being the natural state that we aspire to but can no longer achieve. In sonic terms, Brinkmann, you could say, tries to bridge the gap.

When contrasted with much more expensive equipment from CH Precision, Boulder, and Ypsilon, the Brinkmann gear doesn’t quite have their magnanimity of sound, grip, and airiness. CH Precision produces a cavernous black space that seems unrivaled. Boulder has a degree of control that is unique to it. And Ypsilon lights up the soundstage. But Brinkmann comes remarkably close and has its own set of virtues. It has a dynamism and smooth continuity that are immensely beguiling. It represents formidable German engineering allied to a profound sense of musicality that will be difficult for most listeners to resist.

Description

Description

- Features: Gain trim for each input, phase/invert switch, remote control

- Inputs: 4 Single-ended, 2 Balanced

- Output voltage: Maximum ± 12 V Balanced

- Input impedance: 20k Ohms, Balanced and Single-ended

- Output impedance: < 0.1 Ohms Balanced

- Dimensions: (WxHxD) 420 x 95 x 310 mm (with granite base); power supply 120 x 80 x 160 mm

- Weight: 12 kg; granite base 12 kg; power supply 3,2 kg\

Marconi, Mk II Linestage

Features: Gain trim for each input, phase/invert switch, remote control

Inputs: Four single-ended, two balanced

Output voltage: Maximum ± 12V balanced

Input impedance: 20k ohms, balanced and single-ended

Output impedance: < 0.1 ohms balanced

Dimensions: 420 x 95 x 310mm (linestage with granite base); 120 x 80 x 160mm (power supply)

Weight: Linestage, 12kg; granite base, 12kg; power supply 3.2kg

Price: $13,990